Today 68 years ago, the Republic of Turkey became the first Muslim-majority country to formally recognise the state of Israel, which had been founded in 1948. This recognition, signed by Turkish President İsmet İnönü on 28 March 1949, led to the opening of the first Turkish diplomatic mission in Tel Aviv in 1950.

This notable diplomatic gesture by the officially secular Turkish Republic is reflective of a wider crossover in twentieth-century Turkish, Jewish and Israeli history.

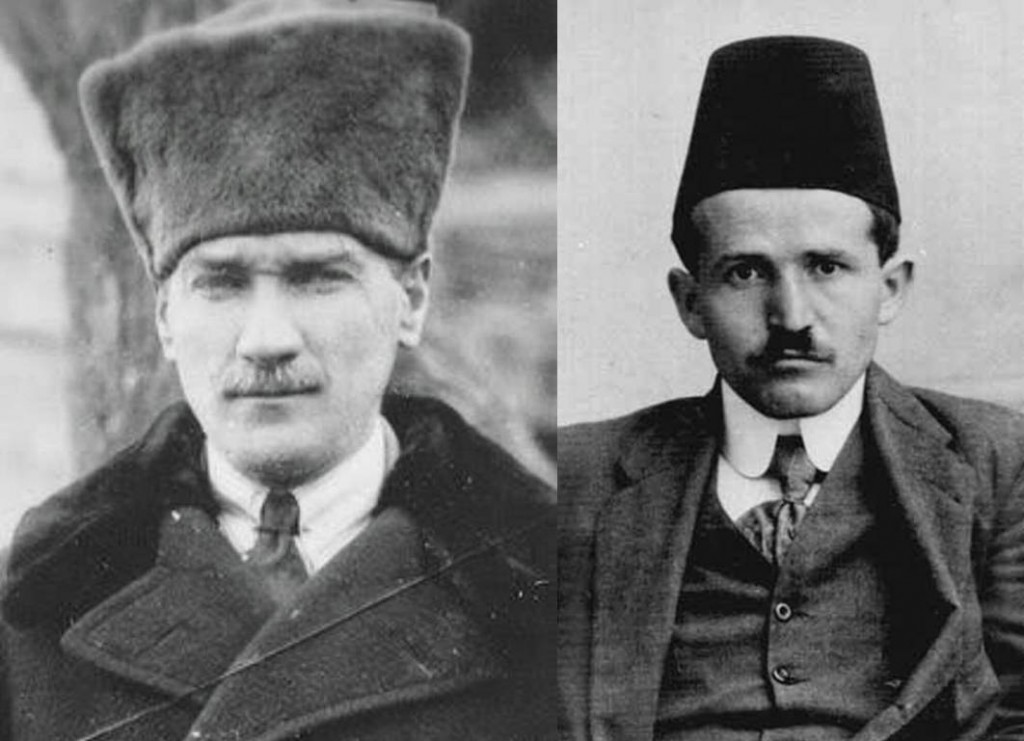

Salonika, the modern-day Greek city of Thessaloniki and birth-place of the founder and first President of Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, is a suitable place to start. This city, once commonly referred to as the ‘Jerusalem of the Balkans’ because of its large Jewish population, was also home at one time to another man who, like Atatürk, would play a key role in re-shaping the post-First World War Middle East.

Israel’s first Prime Minister David Ben Gurion spent formative years in Ottoman Empire

His name was David Ben Gurion – the first Prime Minister of Israel. This young Jewish student of Polish origin and future Zionist leader spent his formative years in the Ottoman Empire. In 1906, aged 20, he arrived in Palestine, living there for a time before moving to Salonika in 1911 to learn Turkish. A year later he transferred to Constantinople – the Ottoman capital – to pursue his studies in law.

Ben Gurion’s early adult life reflected the cosmopolitan experience of many religious minority groups in the late Ottoman Empire. He wore a Fez like any other Ottoman man, a symbol of secular Ottoman citizenship and the required headwear of all officials whether Muslim, Christian or Jewish. He, like many others including Greeks and Armenians, was the beneficiary of the modernising, diverse and tolerant Ottoman State that had been reforming since the nineteenth century that would be undone with the excesses and tragedies of the First World War.

Based in Jerusalem at the outbreak of the First World War, he formed a Jewish militia to support the Ottoman army believing its success would help his own quest for Jewish national autonomy. Nevertheless he was deported by the Ottomans to Egypt in 1915 and from there escaped to the US where he spent three years touring the country trying to raise money to fund his Jewish militia. He switched allegiances after the British issued the Balfour Declaration in 1917, promising a homeland for the Jewish people.

While taking different paths, the visions of both David Ben-Gurion and Mustafa Kemal Atatürk for their respective nation-states emerged from the chaotic collapse of the Ottoman Empire. Both drew from secular European models, and emphasised a cultural and historical relationship to the land, keen to construct an independent country where their people could be ‘the masters of their own fate’.

Given the two people’s historic ties and future aspirations, it was natural for these two non-Arab, secular, and Western-oriented states to form a strong strategic partnership.

Jews had been welcomed by the Ottomans since the Middle Ages, when they were first expelled by Europe. A new influx of Jewish refugees was also received by the Turkish Republic in the 1930s, following the ascendancy of the Nazis in Germany. During this time persecution, violence and intimidation became a common feature of life for German Jews, who were forced out of government employment.

Philipp Schwartz, one of the affected professors, petitioned Turkey’s President Atatürk for help. His acceptance meant over 100 German Jewish academics found refuge in Turkey, and were given work at Turkish universities.

After the establishment of Israel in 1948, almost half of Turkey’s Jewish population, which numbered around 80,000 at the close of the Second World War, would migrate to the newly founded Jewish State.

Turkish-Israeli relations have yo-yoed since 1949

Since Turkey’s recognition of Israel in 1949, ties between the two countries have yo-yoed. After the Israeli occupation of the Suez Canal in 1956 for instance, Turkey downgraded its diplomatic presence in Tel Aviv, only to upgrade it again to consulate level in 1963. This representation was upgraded once more to ambassadorial level in 1980, but was decreased later that year after Israel declared Jerusalem to be its capital.

Relations were again strained in 1988 with Turkish recognition of a Palestinian State established in exile, but improved with the initiation of the Middle East peace process in 1991. These developments subsequently saw Israel and Turkey establish bilateral defence, security and economic partnerships between 1994 and 1998, which burgeoned into strong social and cultural ties between the two countries.

This ‘Golden Age’ of diplomatic relations remained steady and positive for much of the new millennium. While serving as Foreign Minister, the former Turkish President Abdullah Gül paid a visit to Israel in early 2005, which was followed by the then Prime Minister, now President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in May the same year.

With Turkish assistance, 2005 also saw Israel conduct its first diplomatic contacts with Pakistan at a meeting of foreign ministers in Istanbul. The Israelis then reciprocated this warmth in a ground-breaking manner when President Shimon Peres visited Ankara and addressed the Turkish Parliament in November 2007.

Security co-operation arrangements, including the Israeli Air Force undertaking training exercises in Turkish airspace and arms deals, continued and in 2008, the close relationship between both countries meant that Turkey was able to foster indirect peace-talks as a mediator between warring Israel and Syria. Later that year however, these warm ties soured after Israel went to war in Gaza after it was subject to missile attacks from that area.

Following Israel’s Gaza assault, Prime Minister Erdoğan made a fierce verbal attack on President Peres at the 2009 World Economic Forum in Davos. Angry at being cut short by the panel moderator, the Turkish leader told the Israeli President, “When it comes to killing, you know well how to kill”, before walking out of the conference.

Relations deteriorated to their very worst in 2010 with the infamous Mavi Marmara incident. The passenger ship was part of a six-ship flotilla attempting to break the Israeli blockade of Gaza when it was raided by Israeli commandos in international waters, leaving eight Turkish citizens and one American citizen of Turkish background dead. A tenth activist died of their injuries in hospital in 2014 after being in a coma for four years.

Although trade between both countries continued, this like other parts of their relationship deteriorated. Ankara expelled the Israeli ambassador and froze military co-operation. There were increasingly angry, anti-Israeli outbursts from PM Erdoğan and his supporters, prompting accusations of anti-Semitism from some quarters.

The state of affairs grew so poor that award-winning New York Times columnist Tom Friedman went from lauding Turkey as a model for the Middle East in 2005 to writing shortly after the Gaza flotilla raid that the Turkish Government seemed to focus “not on joining the European Union but the Arab League — no, scratch that, on joining the Hamas-Hezbollah-Iran resistance front against Israel.”

Strategic interests pave way to restoring relations

Following an apology from Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in March 2013 acknowledging “operational mistakes” however, the first steps on a slow road to recovery were made. Last year, the Israelis also agreed to pay $20 million in compensation to the families of Mavi Marmara victims as part of a reconciliation and normalisation agreement with Turkey, while the Turkish Government assisted its Israeli counterpart in recovering four missing Israeli citizens from Gaza by exerting its influence on Hamas.

Recent diplomatic visits between both countries reflect the strategic needs of the two states. While distrust remains among the general public on both sides, the Turkish and Israeli governments have shown a pragmatic willingness to re-establish a co-operative relationship in numerous fields. They are spurred on by the prospect of lucrative Mediterranean gas deals worth billions to their economies, and share mutual fears over growing security risks in the region.

Last month, the Director General of the Israeli Foreign Ministry Yuval Rotem travelled to Ankara to discuss the development of closer economic, cultural, energy and political ties, while the Turkish Minister for Culture and Tourism Nabi Avci visited Tel Aviv to meet his Israeli counterpart Yariv Levin (pictured below).

The once firm allies have since reaffirmed the importance of good ties to the security and stability of the East Mediterranean and Middle East, and discussed soft co-operation as positive steps towards renewing relations.