In January 1877, the Constantinople ‘Tersane’ Conference, attended by the Great Powers including Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Russia, and Austria-Hungary, came to an end. The Conference had started in December 1876, and was intended to address the Ottoman Empire’s problems, commonly referred to by European politicians and diplomats as the “Eastern Question”.

The year 1876 had been troublesome for the Ottomans. Their government was in disarray as Sultan Abdülaziz – accused by leading civil, religious and military officials of being pro-Russian and a danger to the integrity of the Ottoman State – was deposed in favour of Murad V. However, the new sultan’s health was poor and quickly deteriorated, incapacitating him as a ruler. He reigned for just 93 days, before losing the throne to his brother Abdülhamid II.

The Ottoman Balkans had also suffered a huge trauma after a new Christian uprising broke out in Bulgaria. It added to the devastation inflicted by other rebellions in Bosnia, Montenegro and Herzegovina from the previous two years. Such uprisings led to brutal inter-communal violence.

Ottoman Empire’s 1st constitutional era enshrined modern secular with Islamic values

Visionary Ottoman statesmen such as Grand Vizier Midhat Paşa, however, remained keen to demonstrate that the Ottoman Empire aspired to be a modern, enlightened state that governed with the same principles and institutions as the West. On December 23rd – the first day of the conference – they attempted to do just this by announcing the adoption of a constitution to the attending diplomats. It was with this announcement that the Ottoman Empire’s First Constitutional Era began 140 years ago.

In Britain, the text of the constitution was published in English by The Times on 1st January 1877 after an Ottoman official had brought it to the newspaper’s Paris bureau the previous day. The document tells us much about the identity that Ottoman leaders wanted for their homeland, combining both the Ottoman Empire’s modern secular and traditional Islamic attributes.

Article 8 for instance referred to all the Empire’s subjects as “Ottomans” regardless of their religion, while Article 17 specified that ‘all Ottomans were equal before the law’. The Ottomans’ Muslim identity was also preserved by Articles 4 and 11, which designated Islam the state religion and recognised the sultan as “Supreme Caliph” and protector of the faith.

Additionally the constitution included other liberal principles, affording Ottoman subjects certain freedoms such as personal liberty, property rights and a free press within the limits of the law. It also made some provisions for representative government, namely, the first Ottoman Parliament or General Assembly, which had two houses, a Senate whose members were appointed by the Sultan and a Chamber of Deputies that was indirectly elected.

Ethnic minorities represented in first Ottoman Parliament

In keeping with liberal aspirations, quotas were used to ensure that the Empire’s various communities were represented adequately. Istanbul for example, had ten deputies, of which five were Muslim, four were Christian (two Greeks and two Armenians), and one was Jewish.

The parliament, however, lasted less than a year, holding two sessions before being “temporarily suspended” along with the constitution by Sultan Abdülhamid in 1878. Having seen both his uncle and brother deposed the sultan was keen to concentrate as much power in his own hands and away from those officials who had enthroned – and could just as plausibly dethrone – him. The constitution would eventually be restored in 1908 by the Young Turk Revolution.

Although a short-lived period in the Empire’s long history, the First Constitutional Era gives us a valuable insight into the vision leading Ottoman officials had for their country in the nineteenth-century: a modern state with liberal and secular characteristics that nevertheless maintained and stayed true to its Islamic heritage and traditions.

Collapse of talks at Constantinople Conference, 18 Jan 1877

The Great Powers attending the Constantinople Conference, however, failed to recognise the constitution’s merits, instead demanding greater autonomy for key provinces of the Ottoman Empire.

On 18 Jan. 1877, after extensive discussions to try and bridge the gap, Midhat Paşa announced that the talks had collapsed as neither side was willing to accept the other’s proposals. The failure to bring about a solution to the crisis not only prolonged it, but eventually led to the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War in 1877.

Following the Ottoman defeat in 1878 and the resolution of the crisis with the Treaty of Berlin, the Ottoman Empire lost much of its European territory with the establishment of independent states in the Balkans, Serbia, Romania and Bulgaria. The Sultan also ceded Cyprus to Great Britain in exchange for British diplomatic support at the Berlin Congress that produced the treaty.

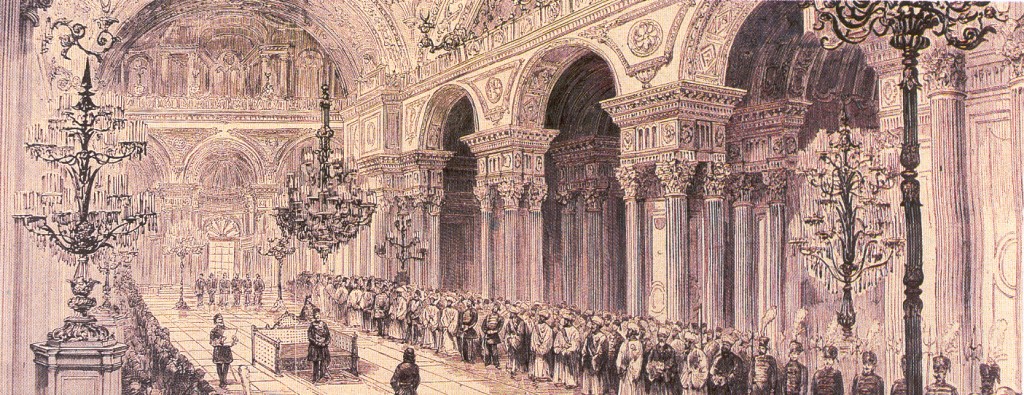

Main image (top) of the opening ceremony of the First Ottoman Parliament at the Dolmabahce Palace in 1876