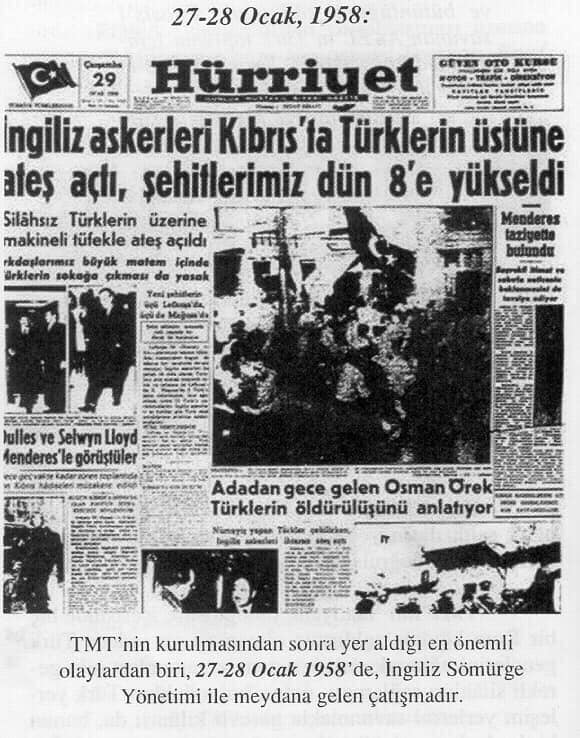

Many violent events occurred in the final years of British colonial rule in Cyprus, but one of the worst – and least known – is the slaughter of seven Turkish Cypriot civilians and the wounding of dozens of others by British troops on 27 and 28 January 1958. This shocking event would have a pivotal impact on the Cyprus Emergency and dynamics between the different parties involved.

Tensions were already high in Cyprus due to the murderous campaign of EOKA, a Greek Cypriot terror group fighting to end British rule and unite the island with Greece (‘Enosis’).

The vast majority of Greek Cypriots had long aspired to turn Cyprus into a Hellenic island, with 96% of the community voting for Enosis in a plebiscite held in 1950.

Greek Cypriot nationalists led the insurgency against Britain, forming the National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters (EOKA) and launching their ‘liberation’ war in 1955. EOKA’s brutal methods included bombings and assassinations, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of police officers, soldiers, and civilians, including Greek Cypriots who objected to their mission.

The British hired more Turkish Cypriots as police officers and commandos to help them combat the threat from EOKA, which put the Turkish Cypriot community directly in the line of fire.

Turkish Cypriot officials and civilians were murdered, their homes burnt down and Turkish Cypriot villages and neighbourhoods were attacked by EOKA militants. Those living in mixed villages were driven out.

This violence formed the backdrop to the events of January 1958, by which time Turkish Cypriots were demanding partition – ‘taksim’ – of the island to prevent further bloodshed. The community was also increasingly at odds with the British authorities over its handling of the Cyprus Emergency.

Turkish Cypriot students at forefront of pro-Taksim protests

Many Turkish Cypriot activists feared the arrival of Sir Hugh Foot as the new Governor of Cyprus in December 1957 heralded a sea change in British policy that would harm the Turkish side, which in turn amplified their cries for ‘taksim’.

Turkish Cypriot high school students were at the forefront of the anti-British, pro-Taksim protests, resulting in small scale confrontations with British forces.

When the boys attending Lefkoşa Türk Erkek Lisesi [Lefkoşa Turkish Boys Senior High School] saw EOKA painted in large letters over the entrance of their school on 21 January 1958, they immediately reacted.

The students first gathered in their school yard to protest the situation before moving to nearby Atatürk Square, where they waved Turkish flags and handmade banners that read “We do not trust Governor Foot” and “Greeks and Turks cannot live together.”

From there they marched to Girne/Kyrenia Gate in the old city, but on their way back they were stopped by British soldiers in front of Turkish Cypriot leader Dr Fazıl Küçük’s house. The soldiers tried to take the flags from the students, who resisted, resulting in the soldiers beating them with batons.

A few days later, on January 25, Turkish Cypriots in Limassol were granted permission to hold a pro-Taksim march. Despite this, the British military and police officers treated them harshly during their demonstration, firing tear gas at the protestors and later arresting several of them.

There was no respite from EOKA during this period, with the group vandalising Turkish schools, breaking windows, daubing graffiti on walls and leaving behind threatening flyers that read, “If you agree to Enosis, we will not touch you; if you do otherwise, your punishment will be death”.

Bozkurt ‘Taksim’ front page creates big buzz

On 26 January, British Foreign Secretary Selwyn Lloyd and Sir Hugh Foot travelled to Ankara for a meeting with Turkish Foreign Minister Fatin Rüştü Zorlu to discuss how to resolve the Cyprus Emergency.

The Turkish Government was onboard with ‘Taksim’, but activists in Cyprus wanted Ankara to take more significant steps to support them.

The British delegation’s visit was announced in a striking front page story in local daily newspaper Bozkurt. The paper’s 27 January edition wrongly claimed that Britain had accepted a proposal by the Turkish government for Taksim, when in fact London had just agreed to review the proposal.

This mistranslation by the paper’s editorial team created a major buzz on the eve of 26 January as the paper came off the printing press. Patriotic Turkish Cypriots took to the streets to celebrate. They walked around the Turkish quarter in the capital city Nicosia for hours chanting, “Ya Taksim, Ya Ölüm” [‘Either Partition Or Death’]. Word quickly spread.

Ya Taksim, Ya Ölüm

Buoyed by Bozkurt’s news, the following day, 27 January, Turkish Cypriot students at Lefkoşa Türk Lisesi [Lefkoşa Turkish High School] decided to skip class and instead hold a pro-Taksim rally and also protest against British colonial rule. They were joined by other young people, who had heard or seen Bozkurt’s front page and had come to the city centre to do the same.

Holding Turkish flags and chanting, “Ya Taksim, Ya Ölüm”, the young demonstrators made their way peacefully across the heart of Lefkoşa. When they reached the Evkaf building near Sarayönü in the old city, events started to turn ugly.

British troops tried to stop the protestors by creating barricades with their military vehicles and firing tear gas at the crowds to force them to disperse. When that didn’t work, they charged at them with batons.

The young protestors refused to go home, changing the direction of their march instead. They headed to two nearby Turkish girls’ high schools and encouraged them to come out and join their protest. Many did. Swelled by the girls’ numbers, the demonstrators once again tried to make their way towards Sarayönü.

Waiting for them were even British troops, who shouted at them through megaphones to go home and again sprayed them with tear gas. When that didn’t work, the soldiers started firing their guns.

The guns shots and other noise prompted Turkish Cypriots living and working nearby to come out onto the streets to see what was going on. When they saw their children being attacked by the British, they quickly went to their aid.

Sarayönü and surrounding streets became full with Turkish Cypriots all now chanting Ya Taksim, Ya Ölüm.

According to one eyewitness report, “Sirens start sounding at 10 o’clock in the morning. According to the law, a curfew was imposed. According to the law, the Security Forces had the authority to fire, but no one cared!

“The Turkish Cypriot youth responded to the British soldiers’ batons and rifles with stones and sticks… British Colonial Administration soldiers had blocked the entrance to Girne Caddesi. There were hundreds of British soldiers and armoured vehicles with guns, shields and bombs in front of [what is] today’s Turkish Bank!…

“The students’ goal from the very beginning was to pass through Sarayönü, walk to Girne Gate and disperse… However, the British soldiers had no intention of allowing this and had already resorted to violence. Against the tear gas bombs, gun and shield attacks of the British, the male and female students had to defend themselves with stones and pieces of wood left over from the banners they carried.”

British soldier deliberately drove Land Rover into crowd, crushing four people

Rauf Denktaş arrived at Atatürk Square, where the clashes were taking place, to try and calm things down. As President of the Federation of Turkish Cypriot Institutions, Denktaş had clout and it appeared the students were going to disperse.

Just then, a British soldier decided to drive his military jeep into the crowd at Sarayönü. He drove his Land Rover at full speed along the 400 metres of road from Girne Gate to Atatürk Square, ploughing into the crowd and crushing four Turkish Cypriots beneath its wheels.

One of the victims was 20-year-old Mehmet Ahmet Bondigo, who died instanstly at the scene. Another was an elderly woman named Şerife Mehmet, who died in hospital.

Troops fire at civilians

Events then spiralled out of control, as the peaceful march turned into a full scale riot. Instead of dispersing, young people started to pelt British soldiers with more stones, who responded by firing back at the civilians.

Teenager İbrahim Ali, 19, was among those injured in the shooting. His friends Mustafa Mehmet and Sermet Ali Kanatlı, both aged 20, decided to drive him to hospital.

As their car tried to drive away, British troops turned their guns on them, killing all three. Their bodies were riddled with bullets.

Film from 1958 of riots by Turkish Cypriots demanding partition of #Cyprus: https://t.co/Ry5m7lTk3c

— john akritas (@johnakritas) February 22, 2017

More Turkish Cypriots were shot and injured by British forces near Çağlayan Park. It was a miracle more people were not killed.

The following day, the riots spread to Mağusa/Famagusta, Lefke, Baf/Paphos and Limassol. A curfew had been put in place, but many Turkish Cypriots ignored it, such was the anger in the community at the five people the British had killed and the wounding of dozens of others.

The British response was again brutal. They fired tear gas at the crowds of civilians who had assembled, and clashed with the protestors, beating them with batons, while other troops fired at them.

It cost the lives of a further two Turkish Cypriots, Fuat Yusuf, 33, and Safa Muharrem, 28, who were shot dead by the British in Famagusta on 28 Famagusta.

Massive crowds march in silence for funerals

Denktaş secured permission for the funerals of the seven Turkish Cypriots, which was attended by thousands of people. The British were struck by the eerie silence that accompanied these mass events.

In his memoirs, Denktaş relays the words from the British Deputy Governor of Cyprus, Sir George Sinclair, at that time.

Sinclair extended his condolences to Denktaş, telling him: “I want you to know that these events have changed our perspective on the Cyprus Issue,” adding, “We did not appreciate until now how much the Turks would press for their rights in Cyprus.”

The British Police Commander also remarked about the way the funeral was conducted, stating, “48 hours of fighting and violence were not as terrible as the silence at the funeral, the necessary message was received.”

The impact of the 27-28 January 1958 riots

The two days of rioting had left seven Turkish Cypriots dead and over 100 people injured. The scale of the violence from British forces over these two days created shockwaves in the Turkish Cypriot community, especially given how Turkish Cypriots had put their own lives on the line to protect the British against EOKA during the Cyprus Emergency.

“The British, who did not use weapons against the Greek Cypriots who were on the streets every day with pro-Enosis demonstrations, rained down brutal gunfire on the Turkish Cypriots for two days,” said İbrahim Açman, the Deputy Chairman of the Martyrs’ Families and Disabled Veterans Association, at a remembrance service to the victims on 27 January 2022.

It became clear to all Turkish Cypriots and to Turkiye that the community needed to mobilise to defend itself not only from EOKA, but if needs be the British. Previous attempts to form Turkish Cypriot self-defence militias, such as Volkan and 9 Eylül Cephesi, had failed to get off the ground.

After the events of January 1958, Turkish Cypriots rallied round the Turkish Resistance Organisation (TMT), which was formally launched in August of that year with the blessing and active support of Ankara, ensuring the community could defend itself more robustly from EOKA attacks.

The British too realised that while the Turkish Cypriots were numerically smaller than the Greek Cypriots, their legitimate needs could not be ignored when considering the future of the island. Nor could the Turkish Cypriots be regarded as blindly loyal to British colonial rule. If anything, the January riots showed the strength of anti-British feeling among the community, with those views significantly hardening after the deaths of the seven Turkish Cypriots.

The demands for ‘taksim’ grew louder after this time. The demand was amplified in London by the thousands of Turkish Cypriots who had emigrated there to escape the EOKA-driven violence, and who would hold massive rallies in central London to ram the message home to British politicians and media that they wanted Britain out and self-rule for Turkish Cypriots.

The future trajectory of the talks to resolve the Cyprus Issue also changed, with Turkiye adopting a more hardline position to support the demands of the Turkish Cypriots, who evolved from being a ‘minority community’ to a people with their own identity and rights.

A year later, the key parties, Britain and the two motherlands, Greece and Turkiye, along with the Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots, struck a deal for Cypriot independence in two meetings held in Zurich and London in February 1959.

Among the collection of agreements were the future constitution of the Republic of Cyprus, which would see Turkish Cypriots and Greek Cypriots share power as political equals.