“Kardeş kardeşi satmaz,”Rukiye Turdush, a Canada-based advocate for the persecuted Uyghur minority in China said, switching from her local Turkic dialect spoken in China’s western Xinjiang region to the Anatolian dialect spoken in Turkey.

A brother does not sell out his brother. “Uyghurs never lose hope in Turkey. They strongly believe that sooner or later Turkey will stand up for them.”

This hope was expressed by many Uyghurs I came across throughout my years in Istanbul, home to a sizeable community who migrated to Turkey over the decades. Oppressed and persecuted in their restive homeland, which they prefer to call East Turkestan, many Uyghurs came to Turkey seeking a safe haven. The cultural familiarity of Anatolia, whose people, like the Uyghurs, trace their ancestry back centuries to the foothills of the Altai mountains in Central Asia, made Turkey a perfect place for them to restart their lives.

For a long time, Turkey seemed to be the only friend of the Uyghur people, who in Xinjiang have suffered decades of repression and crimes against humanity. Uyghur women have been forced to have abortions, and nuclear testing in the region’s Taklamakan desert have led to cross-generational birth defects due to genetic mutations stemming from prolonged radiation exposure.

The Chinese government has also been under fire recently, with UN human rights experts in August reporting violations of cultural and religious freedoms against the Uyghur people and Chinese authorities turning Xinjiang into a surveillance state.

The Uyghurs, who are Muslims, are seemingly banned from displaying any form of Islamic identity. Those caught praying, wearing headscarves, fasting in Ramadan or even following traditional Islamic funeral customs are being sent to “re-education centres”where they are forced to eat pork, drink alcohol and denounce their cultural and religious values. Some reports even suggest that Uyghur women are forbidden from rejecting marriage proposals from Han Chinese men. According to the UN, as many as one million Uyghurs may be in these centres, which have been likened to Nazi-era concentration camps.

In 2009, Turkey’s then PM Recep Tayyip Erdoğan described China’s behaviour towards the Uyghurs as “a kind of genocide”

In 2009, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, then prime minister, said China’s behaviour towards the Uyghurs was “a kind of genocide”. Just as Turkey has done for refugees fleeing war in Syria, it has also long kept its door open to Uyghurs escaping China, even offering to take in Uyghurs stranded in other countries to avoid them being deported back home. But there has been a change as of late.

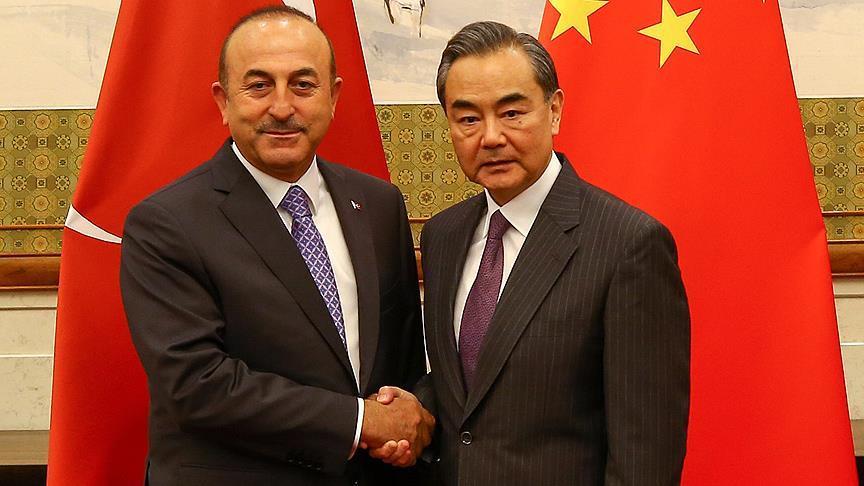

In August 2017, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu in a press conference with his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi promised that the Turkish government “absolutely will not allow in Turkey any activities targeting or opposing China,”additionally vowing to “take measures to eliminate any media reports targeting China” in Turkey.

Çavuşoğlu’s comments came as Ankara and Beijing sought to boost economic cooperation between the two countries in a bid to revive the old Silk Road trade route across the Eurasian landmass. In July, Turkey’s Finance Minister Berat Albayrak confirmed China had invested $3.6 billion into the Turkish energy sector. Since then, the Uyghur issue has been constantly played down, and news about the crisis in Xinjiang have all but disappeared from Turkish media.

Media blackout

One Uyghur I met at a restaurant in Istanbul, who asked not to be named, pointed out that while Uyghur protests against China have not been outright banned in Turkey, they have been limited to smaller squares in inconvenient places, whereas they used to be given permission to demonstrate in larger and more accessible squares in the past. Meanwhile, a journalist working for an independent Turkish newspaper with close ties to the country’s governing AK Party, also speaking anonymously, said he believed there was some kind of unofficial media blackout in force.

“We used to cover the Uyghur story very well before. There was a time when our editors would demand we cover the story. But in the past year specifically we haven’t really covered it,” the journalist said.

“While the world discusses concentration camps in East Turkestan, we carry on like nothing is happening. I have pitched stories on it a few times, but each time I received no reply. They don’t ever tell me ‘no’, but they just pretend to forget about it.”

“They’re not like that with other stories. Ironically they’re fine with covering Taiwan, Hong Kong and Tibet. But the Uyghur case is a mystery. There’s no written policy saying we can’t pitch about Uyghurs, but generally no one pitches any more because they know it’ll hit a wall,”the journalist added.

The lack of media coverage certainly hasn’t gone unnoticed by the Uyghur community. “Most Uyghurs are feeling disappointed about the lack of attention in Turkish media,” Rukiye Turdush said.

“Meanwhile they try to understand Turkey’s difficulty in defending its moral and religious obligations against China, because Turkey is in a weak position and needs China since its relationship with the US deteriorated.”

“Turkey always does what it can for the Uyghurs. Right now there are many Uyghurs living in Turkey, and Turkey takes care of all of them… for this we actually thank Turkey,” she continued in her watered-down Uyghur dialect, which is perfectly comprehensible by Anatolian standards.

“But we don’t want Turkey to get trapped by Chinese money. Dangerous Chinese nationalism will be exported through the Chinese imperialistic dream and countries signed up to OBOR will be affected the most if no one dares to stop China,”she said, referring to Beijing’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative, the official name for the Silk Road project.

However, Nesibe Flora Kurt, an Uyghur activist and researcher who has been living in Turkey since leaving Xinjiang as a child, did not strike such a conciliatory tone. “I don’t think Turkey, as an administration, is seriously and consistently following up on this issue,”she said. “Turkey is unable to pick up the Uyghur issue at the right moment and the right point in their diplomatic relations with China, because we provide no benefit for them.”

“Uyghurs always had hope in Turkey. There was once a time that whenever Uyghurs would travel to Mecca to perform the Hajj pilgrimage, it was almost a religious obligation to visit Istanbul first,” Kurt said.“Unfortunately, this hope is no longer what it was.”

Nowhere else to go

Yet, there is another issue at hand. In the past, Uyghur suffering was generally confined to Xinjiang. But now, as Chinese soft power reaches further beyond its borders, Uyghurs are beginning to feel nowhere is safe. In recent years, Uyghurs escaping China have been deported from Egypt, Thailand, Malaysia, the UAE and even European countries such as Germany and Sweden due to Chinese political pressure. More often than not, when they returned to China, their fates became unknown. Uyghurs also face the threat of being hunted down outside of China by Chinese agents.

Following a string of assassinations, most notably the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in October, political dissidents from the Middle East and Central Asia no longer see Turkey as a secure location to set up camp.

Last year, one of my closest friends, American journalist and Syrian regime critic Halla Barakat, who I actually wrote about in an earlier T-VINE article in which I mentioned her support for Turkish Cypriots, was also tragically killed along with her activist mother in Istanbul after receiving threats for years. Likewise, Uyghurs in Turkey have been no exception to harassment at the hands of foreign spies operating in the country.

In a November 2018 article published in The Independent, one Uyghur man living in Turkey, identified only as “Eysa”, explained how Chinese intelligence agents have been working to coerce him into spying on his community in Istanbul. Having first been detained after returning to China following a trip to Turkey in 2015, Eysa said an intelligence agent by the name of “Qurban” blackmailed him into agreeing to become a spy. Eysa, however, told the newspaper he only agreed because it was the only way to get his passport back. This incident was repeated in 2017, again after a trip to Turkey, in which Qurban asked him why he hadn’t kept his promise. It was then that Eysa decided to move to Turkey permanently with his family, but the Chinese agent continues to leave him threatening messages on his phone.

“Eysa… You think you’re safe in Turkey. But what about your brothers and in-laws?”his interrogator is heard saying in a recording played for The Independent. “Yes, you are in Turkey… but your brother, brother-in-law, and father-in-law are in our hands. If we torture them it’s on you. Think about that. We are very powerful and we can reach you wherever you are,” Qurban says in another recording.

Abduweli Ayup, an Istanbul-based Uyghur activist, also recalls similar stories of members of his community who have been harassed by Chinese intelligence. He told The Independent that a Chinese agent once contacted his friend via video chat in which the man was shown his terrified elderly parents who had been detained in China. The agent told him to collect information on Uyghurs in Turkey or else his parents would be imprisoned. Speaking to the Financial Times, another Uyghur man who fled to Turkey in 2016, identified only as “Tursun”, also complained of harassment by Chinese agents. “In veiled threats, [the officer] said we can monitor you 24 hours a day, so do not think that you can get away with illegal activities in Turkey.”Tursun says he now wishes to leave Turkey.

For what it’s worth, many Uyghurs living in Turkey can’t even turn to the Turkish authorities for help. While Chinese embassies and consulates are refusing to renew expiring passports for Uyghurs living abroad in an attempt to lure them back to China, a number of Uyghurs living in Turkey are experiencing difficulties renewing their residency permits.

Ayup, who fled to Turkey after spending 15 months in a Chinese prison for teaching the Uyghur language, now depends on unofficial translation work to survive as he is no longer legally entitled to work in Turkey, despite once being a visiting scholar at Turkish universities. In September, an Uyghur woman by the name of Rushengul Tashmuhemmet was detained by Turkish police at Istanbul’s Ataturk Airport after travelling from Almaty with her young son. She was held at the airport for four days before finally being allowed to enter the country where her husband and other children were waiting. Tashmuhemmet, whose husband had previously been jailed by Chinese authorities in Xinjiang for seven months, told Radio Free Asia she had been detained because of a “problem” with her passport.

“Due to their passports expiring and obstacles in bureaucracy, Uyghurs in Turkey cannot get their residency permits,”Nesibe Flora Kurt said. “They need to work here, but they cannot find jobs because they don’t have a permit. We are going through difficult times.”

“Uyghur youth in Turkey can’t contact their families in China. They can’t contact China or send money to their parents,” Kurt added. “In the past two months, more than 4,000 Uyghurs in Turkey have applied for asylum in Canada. Just think, Canada is saying ‘we understand your suffering, if you are suffering in Turkey, come to our country’. Western countries spoke out against China at the United Nations, but Turkey didn’t,” Kurt explained.

“While the Turkish people are very sincere and warm towards us, the authorities are not. That is our situation.”

About the author: Ertan Karpazli is a British-born Turkish Cypriot based in Istanbul. He is currently working for Turkey’s English-language public broadcaster TRT World. He was one of the founding members of Cezire Association, a cultural NGO dedicated to the research, preservation and revival of Turkish Cypriot history and heritage.