Turkey’s referendum result is undoubtedly a serious setback for Turkey’s long and torturous process of democratisation – but it’s not difficult to find signs of hope.

The mood of NO supporters in the recent referendum on changes to Turkey’s constitution which dramatically expand the powers of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan ranges from manic depressive to indignant.

And yet there are reasons not to give up hope on Turkey, the only Muslim majority country with a meaningful, if flawed history of democratic culture and process.

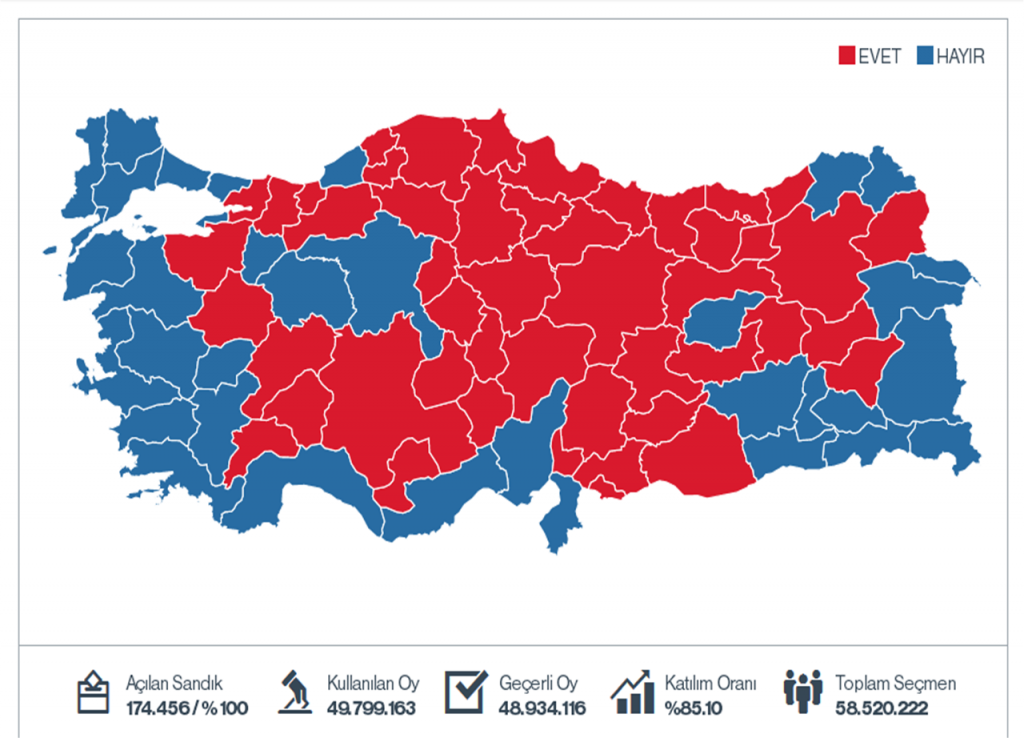

Turkey’s electorate is certainly engaged. The country has one of the highest turn out rates in the world: 85% in this referendum. Just over 25 million people voted YES while 23.7 million people voted NO.

Despite a campaign heavily stacked in favour of the YES side – 90% of broadcast time, state sponsored propaganda and rallies, pressure on NO campaigners – the key cities of Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir all voted NO. This represented the first ‘loss’ for the Justice and Development Party (AKP) in Istanbul and Ankara since coming to power in 2002. The list of provinces which voted NO includes nearly all those which contribute the most to Turkey’s economic and social development.

85% turnout for the referendum

Yes, it is important to accept the reality that no matter how close the vote was – the constitutional changes are still going to pass.

But it is also important to note that shifting demographics and voting patterns do not necessarily bode well for the AKP in the long term. Nationalist voters were clearly not carried by Devlet Bahçeli’s Nationalist Action Party (MHP), who also campaigned for YES and whose MPs were instrumental in opening the path to a referendum in the first place.

Meral Akşener, a MHP dissident expelled from the party by Bahçeli and who campaigned across the country for a NO vote, looks likely to be one of the key beneficiaries despite being on the ‘losing side’. A new party on the centre right led by her could attract significant support from both disillusioned AKP and MHP voters.

“Shifting demographics & voting patterns do not necessarily bode well for the AKP in the long term”

Key questions remain for the Republican People’s Party (CHP), whose leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu has been criticised by some of the party faithful for not being forceful enough in the aftermath of the referendum. The CHP is challenging the results on the basis of a decision by the High Elections Board (YSK) to accept ballot papers which were not stamped by ballot box chairs.

And yet it should also be noted that despite the CHP’s vote rarely troubling the high twenties, Kılıçdaroğlu was the most visible campaigner for the NO side which went on to gain 48% of the vote and the party is likely to have built up its local presence in the course of a difficult campaign. There is a thirst for good opposition in Turkey which is currently not being sufficiently answered – part of the reason is the CHP’s continuing failure to connect with voters across the country.

Commentators point to the challenges which Erdoğan must now face. Hürriyet columnist Murat Yetkin reiterates the sociological differences between the provinces which voted for either side and adds that the majority of people that voted NO were not just opposing a ‘one man system’ but also Turkey’s drift away from European values, the reigniting of the debate surrounding the death penalty and a lack of freedoms.

As Yetkin says, Erdoğan was clearly hoping for at least 55-56% of the vote. He now struggles to put a pragmatic spin on the results for journalists and international allies while revving up his core voters with rhetoric on the death penalty and ‘crusades’. Erdoğan may increasingly find it difficult to reconcile the still heterogeneous nature of AKP voters with his own instincts.

The next few years in Turkish politics will be very interesting indeed – and nothing is a given. This alone is reason to hope.

David Walsh is International Relations Officer at the Board of Deputies of British Jews and writes here in his personal capacity.

Top illustration: Turkey’s 2017 constitutional referendum results by province. Red for areas where Yes votes were in the majority. Blue for No. Map by NTV.