The historic birthplace of a leading Turkish-Azeri intellectual recently returned to Azerbaijani hands following a truce with Armenia. The town of Shusha, the home of the educator, publicist, Pan-Turkist thinker and politician Ahmet Ağaoğlu, who played an important role in the foundation of both Azerbaijan and Turkey, was among a number of areas brought back under Baku’s control after weeks of fighting in the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region, which is internationally recognised as part of Azerbaijan.

The agreement, brokered by Russia, allows Azerbaijan to hold onto all the territory it regained during the conflict, and established a timetable for the withdrawal of Armenian forces from several parts of the region.

Long before this conflict started however, a son of Shusha, Ahmet Ağaoğlu would leave noteworthy marks on his two countries, Turkey and Azerbaijan. A monumental figure, he spent many years striving for the advancement of his people, witnessing the collapse of two empires and the birth of two of the nation-states that replaced them. His life and experiences reveal a rich tapestry of stories, ideas and events from which we can learn much about the history of his countries, as well as those that preceded them.

Born in the year 1869 to an Azeri Shi‘a Muslim family, Ağaoğlu grew up as a subject of the Tsar. At times, the Azeris and other subject communities enjoyed a degree of autonomy under Russian rule. Religious minority leaders for example, were able to continue educating their communities, provided they acknowledged the authority of their rulers, in a manner not dissimilar to the Millet system which existed for centuries in the neighbouring Ottoman Empire.

According to the historian A Holly Shissler, Ağaoğlu witnessed a fascinating instance of this relationship in action during his early education in a local religious school or mektep. Recorded in his memoirs, he described a scene that occurred after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881. His religious teacher or ahund came into the classroom distressed at the news of the Tsar’s death, and ordered the boys to stand up and face Mecca before reading out a eulogy and denouncing the perpetrators as “vile sons of dogs.” “Later on” Ağaoğlu wrote, “I heard that the ahund had sent the eulogy to the Governor General of the Caucasus in order that it be presented to the new emperor in St. Petersburg and that in return for this he had been favoured with a gift of money.”

Following the boy’s religious studies, Ağaoğlu’s mother – wowed by a relative’s impressive military uniform – was also keen that her son receive a formal education in a state school. She had arranged for him to have secret Russian lessons, unknown to his father and traditionalist uncle, in preparation, and Ağaoğlu was later sent on to Russian schools.

“Ahmet Ağaoğlu is an embodiment of the well-known Turkish phrase that Turkey & Azerbaijan are “tek millet, iki devlet” – ‘one nation, two states’”

According to his memoir written years later, at one point, he was one of three Turkish students in his class of 45, while the rest were Armenians. At another, he was one of five Turks, all of whom were regularly bullied by their Armenian peers; later he wrote “The majority of my friends could not endure this and left school. Of the Turks, I was the only one who made it to the last grade.”

Leaving Shusha, he spent his final year of school in Tbilisi, before heading onto St. Petersburg in 1887 to begin his studies at the city’s Polytechnic Institute. While at the institute he lodged at a rooming house for Caucasian students, and much like before, he was one of three or four Turkish or Tatar students, out of 35-40 pupils, but shared a greater sense of camaraderie with his Armenian classmates, all of whom were far from home.

While in in St. Petersburg Ağaoğlu got involved in the city’s political and intellectual life, joining the Revolutionary People’s Party, but his studentship at the institute was cut short. According to notes later produced by his son, Ağaoğlu was deliberately made to fail one of his exams and leave the school by an anti-Semitic instructor who had mistaken him for being Jewish and asked him questions outside of the course’s syllabus.

However, where one door closed, another opened, and the young man set his sights on pursuing academia abroad. He arrived in Paris in 1888, becoming the first ever Caucasian Turk to study there. He would return to the Caucasus after six years, having studied Law and “Oriental Languages” at the École Pratique des Hautes Études.

While in France, Ağaoğlu wrote a number of articles between 1891-1893 in different journals, covering a variety of topics, such as the then ongoing British tobacco monopoly in Iran and the protests that followed it. His writings on the situation in Iran included harsh denunciations of Britain’s actions, the Shah’s government, and double standards in the European press – which regularly raged about the oppression of Christians by Muslims, but rarely acknowledged it when the tables were turned – but above all, shed light on the debilitated condition of the Muslim-majority world vis-à-vis the West.

“The fate of a Muslim peasant, woman, or small businessman is a thousand times worse than that of an Armenian in Kurdistan who is constantly protected by foreign consuls while the former group are left completely at the mercy of grace and favour” he wrote, “and whenever a Middle Eastern Christian wants to improve his lot – how enthusiastic, how approving, how sympathetic all the European papers are! But when it’s a Muslim that aspires to progress – what sarcasm, what irony!”

His experiences in France coupled with his acute awareness of the economic and political dominance of Russians, Armenians and other non-Muslim groups in his native Azerbaijan, led him to conclude that a progressive, unifying national identity could help his people back at home to improve their conditions while remaining loyal subjects of the Tsar.

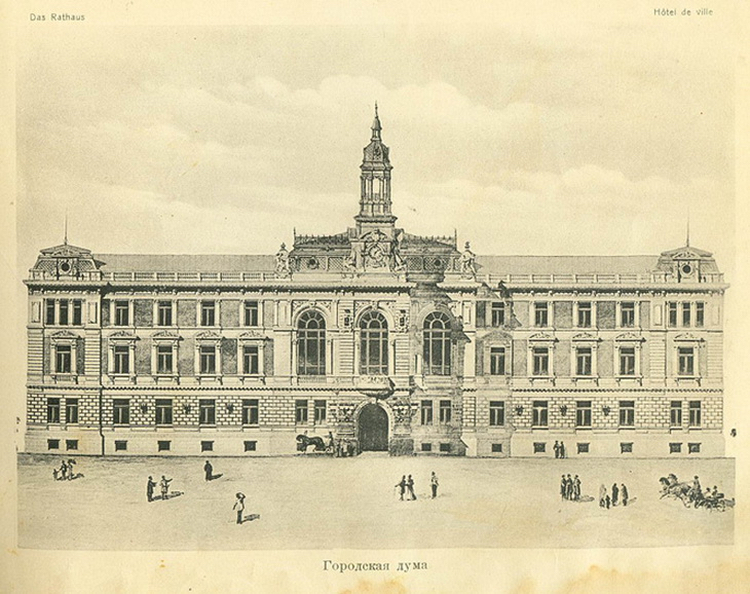

“Ağaoğlu grew incredibly active in his community. He was elected to the local Baku Duma (assembly), and became a political organiser”

Having completed his studies, Ağaoğlu headed back to the Caucasus in 1894 upon hearing about his father’s death. After returning to Shusha, he married his wife, Sitare Hanım, with whom he would have five children. From Shusha, he went on to Baku, taking up a job as a French teacher, but keeping up his writing.

After the 1905 Russian Revolution, which led to an edict promising a new, elected consultative body to address the needs of all subjects, and increased political liberties, Ağaoğlu grew incredibly active in his community. He was elected to the local Baku Duma (assembly), and became a political organiser. He also busied himself in the cultural sphere, touring the region and supporting the establishment of schools and educational institutions far and wide. Before long, Ağaoğlu was catapulted onto the national stage.

Shortly after the revolution, the Tsar invited subjects to prepare recommendations on how he could help them improve their conditions. Many communities, jumped at this opportunity including the Caucasian Muslims, who decided to send a delegation that April to meet Russia’s Interior Minister Alexander Bulygin in St. Petersburg. The delegation, of which Ağaoğlu was a part, drew up a petition with a number of demands such as greater representation in city dumas, access to high office in both the civil service and military, and the right to educate and publish in their own language.

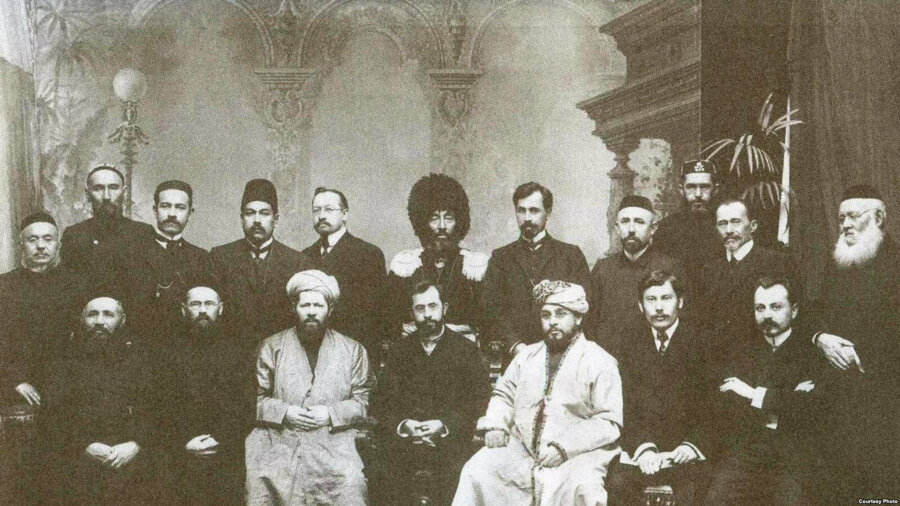

While in St. Petersburg, members of the Azeri delegation met with dignitaries from other Turkic Muslim communities from elsewhere in the empire. Coming together in the home of Abdurreşit Ibrahimov a Siberian Tatar Islamic scholar and journalist –who later became the first imam of the Tokyo Mosque in 1938 – the group founded the İttifak-i Müslimin or Muslim Union to represent Muslims across Russia.

The union agreed to meet again in Nizhny Novgorod in the August of that year for its first congress, which was held aboard a boat as local authorities refused their request for a permit. The meeting passed a resolution calling on Russia’s Muslims to join together and work for equal rights to other subjects of the Tsar, a free press and association, among other goals. Ağaoğlu was intimately involved in the union’s activities, helping to draft its platform.

The union’s second congress continued in the spirit of unity by recognising Shi‘ism as the fifth mezhep (school of law) in Islam, alongside the four Sunni schools, helping to further integrate Azeri Shi‘a Muslims who often saw themselves as culturally Persian rather than Turkish – including Ağaoğlu himself – further towards a Turkic identity.

The union’s active Azeri members achieved some of their stated aims, managing to win official permission to open publications in their own language. For his part, Ağaoğlu edited a number of Baku daily papers, including İrşad (Guidance) which he co-edited with his brother in law, Hayat (Life), and Terakki (Progress). Writing in Hayat, Ağaoğlu called upon the Tsarist authorities to grant their Muslim subject communities political autonomy within the empire. More interestingly, he made his case by arguing that consultative government was part of both Turkic and Islamic customs, showing his increasing identification as a Turk as well as a Russian Muslim.

While this time was one of great political and cultural activity in the Caucasus, it was also one of bloodshed. Inter-communal violence between Armenians and Azeris erupted in Baku amid growing radicalisation and violence among Armenian nationalist groups towards the Tsar’s government for its Russification attempts against them.

European accounts claim that the violence was brought on by the death of an Azeri man or “Tatar” – this term was used to describe any Turkic Muslims in Russia – following a dispute between his family and an Armenian, with riots beginning after his funeral. The violent outbursts, resulted in massacres, attacks and counter attacks, that spread beyond Baku and into the surrounding area. Russian Cossacks entered the city and restored order, while both Azeri and Armenian religious leaders publicly paraded through the streets calling for calm, though violence broke out months later in August, lasting until the spring of 1906.

“He carved out an important role for himself, joining the CUP and getting elected to the Ottoman Parliament as the member for Karahisar in 1912”

For his part, Ağaoğlu travelled the region during the second bout of violence, pleading with his people to work toward peace, but also secretly organising self-defence groups in response to heightened Armenian nationalist paramilitary activities.

While Ağaoğlu and his colleagues enjoyed greater freedoms in the aftermath of the 1905 revolution, before long the Russian regime was on the Azeri journalist’s heels. Upon learning that the authorities were planning to arrest him, he fled to the Ottoman Empire, which had only just witnessed a revolution of its own in 1908.

Making use of the connections to the new Committee for Union and Progress (CUP) Government that he had made in Paris, Ağaoğlu found a warm welcome in Istanbul. In 1909 he took up his first job as a school inspector before becoming the director of the Süleymaniye Library. He also took up a position at the Darülfünün (present-day Istanbul University) as the institution’s first ever teacher of Turko-Mongolian history. He carved out an important role for himself, joining the CUP and getting elected to the Ottoman Parliament as the member for Karahisar in 1912.

Ağaoğlu continued to write and publish on the issues of the day in his new home. Unlike his native Azerbaijan and elsewhere in the Russian Empire where his fellow Turkic Muslims were a minority group pursuing equality, in the Ottoman Empire, his compatriots were a core part the dominant and governing group. This meant that his focus had to shift from promoting Muslim and Turkic identity to galvanise his people to campaign for recognition by their government, to helping his new government hold their empire together and protect it from external enemies.

Ottoman leaders had long been discussing how best to use identity and national sentiments to encourage loyalty to their state. The inheritors of a diverse empire, Ottoman leaders had tended to avoid ideas of nationhood that focused on the cultures, ethnicities or languages of different subject groups. Instead they emphasised commonalities shared by as many citizens as possible, proposing both secular and religious answers.

The reforming Sultan Mahmud II (r.1808-1839) promoted a secular, civic national identity known as “Ottomanism” which was aimed at uniting the empire’s diverse citizens regardless of religion. The sultan is even quoted as saying, “From now on I do not wish to recognise Muslims outside the mosque, Christians outside the church, and Jews outside the synagogue.”

Symbols of “Ottomanness” were also introduced during his reign, such as the fez, which was to be worn by all Ottoman officials regardless of their faith, with the exception of religious functionaries who could continue to wear traditional garb. This approach is understandable for Mahmud’s time, especially when considering that his reign coincided with Greek independence.

After the departure of most of the empire’s other Balkan territories, and with them large numbers of Christian subjects, after a war with Russia in the 1870s, another sultan, Abdülhamid II (r.1876-1909) favoured a more Islamic national identity, with the intention of inspiring loyalty among his now overwhelmingly Muslim subjects including Arabs, Kurds, Albanians and others, as well as Turks.

The sultan also intended to use his role as the global leader or caliph of Sunni Islam to his advantage in the international arena against Britain, France and Russia, all of whom ruled large Muslim populations in their own empires and had snapped up pieces of Ottoman territory.

Concerns over the caliph’s influence on the sentiments of their Muslim subjects certainly played on European minds, particularly among British officials who feared the potentially catastrophic consequences of “Pan-Islamism.”

The arrival of non-Ottoman Turkish intellectuals such as Ağaoğlu around the time of the 1909 deposition of Sultan Abdülhamid by the CUP, greatly impacted the genesis of another strand of national identity for the Ottoman state, namely a focus on Turkishness known as “Pan-Turkism.” Born and bred beyond the Ottoman domains, Turks like Ağaoğlu did not share the same imperial hang ups as their Ottoman counterparts, and often felt more confident in expressing their Turkic identity.

This new trend did not replace the empire’s other two identities, but was intended to complement them. While the empire still emphasised its Islamic nature to Turkish and non-Turkish Muslims alike, both within and outside its territories, pan-Turkism added an extra dimension, intended to strengthen ties with Turkish subjects, especially in the imperial heartland of Anatolia, and further illicit the sympathies of Turkic peoples abroad, especially in Russia. Indeed, during the First World War, Ottoman agents were sent abroad to stir up both religious and Turkic sentiments among Muslim populations in Central Asia, Afghanistan, India and elsewhere.

For his part, Ağaoğlu was deeply involved in promoting pan-Turkism inside his adoptive country. In 1911, Ağaoğlu and his colleagues, including the Russian-born Tatar intellectual Yusuf Akçura and fellow Azeri, Ali Hüseyinzade, founded Türk Yurdu, a new journal. The publication featured articles on matters concerning Turks both at home and abroad in equal measure, encouraging readers to think about themselves as part of a wider Turkic world. By its final publication year in 1931, the journal’s readership would number in the thousands.

Perhaps the most impactful and lasting project of Ağaoğlu and his colleagues for the Turks living within the Ottoman Empire, however, was the Turkish Hearths or Türk Ocakları.

Officially commissioned in 1912, the hearths functioned as local educational and cultural clubs with a pan-Turkist flavour. Despite an initially slow start, they soon mushroomed across the Turkish-populated regions of the empire, boasting a membership of 3,000 in 1914, which grew tenfold by 1920. In fact, the hearths outlived the empire, and continued to operate in the Republican period until the early 1930s.

Dotted throughout Anatolia, they played an important role in organising the resistance movement during the Turkish War of Independence which led to the foundation of modern Turkey. During the early years of the republic, the hearths were used to promote the pro-Western ideals of the newly established country, teaching the new latinised Turkish alphabet, European languages, offering classes for women and establishing libraries. They also hosted theatrical and Western musical performances, as well as sporting activities.

While the new government disavowed pan-Turkism and focused on the Turks at home, hearths still received requests to open branches outside of Turkey in Bulgaria and Azerbaijan.

Unsurprisingly, Ankara dissolved the hearths in 1931, converting them into Halk Evleri (People’s Homes), which carried out a very similar function, but with full commitment to the values of President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and his ruling Republican People’s Party (CHP). The Halk Evleri continued to operate until 1953, when the Democrat Party under Prime Minister Adnan Menderes closed them down for their connections to the CHP.

During this period however, Ağaoğlu did not forget about his native Azerbaijan. In 1918, he joined an Ottoman force known as the “Army of Islam” as a political advisor, and travelled back to the Caucasus under the leadership of Nuri Paşa, the half-brother of the War Minister Enver Paşa, both of whom were committed pan-Turkists. The army captured Baku, and supported the establishment of a new, friendly, independent Republic of Azerbaijan, which the Ottomans had hoped could be used as a buffer between their own empire and Russia.

Before long, the CUP Government collapsed and its successor signed the Mudros Armistice with the Allies, ending Ottoman involvement in the war. Though ordered to withdraw, Nuri permitted his troops to transfer over to the Azerbaijani side and stay there. For his part, Ağaoğlu decided to stay and led a delegation to meet with the British Expeditionary Force that then dominated Northern Iran, to negotiate the terms of their coming occupation of Azerbaijan.

“With his native Azerbaijan now a part of the Soviet Union, he joined another Turkish cause, travelling to Ankara to support Atatürk in the War of Independence or National Struggle”

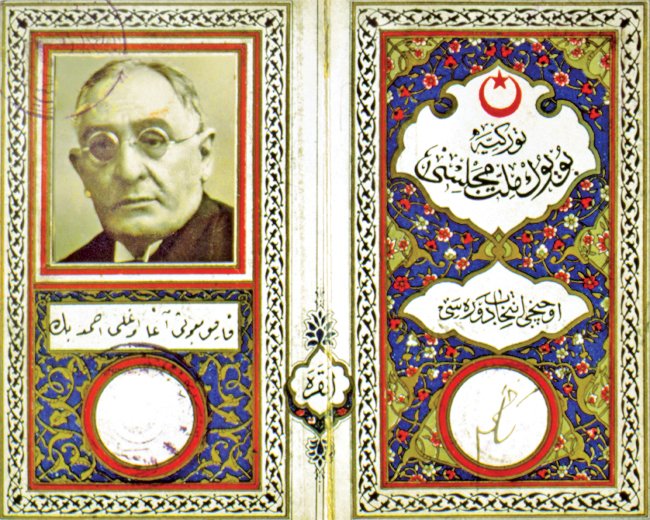

Under British occupation the new state elected a democratic parliament. Ağaoğlu won a seat, serving in his second national legislature. The question of whether the international community would recognise the new republic as an independent country was to be discussed at the post-war Paris Peace Conference. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Ağaoğlu was selected as one of the negotiators to represent Azerbaijan during the peace talks. However, he never reached his destination.

After being stalled by delays in issuing a visa at the French side and a bout of Spanish flu, he was subsequently arrested by the British in 1919 and imprisoned on Malta until 1921. He was accused of committing atrocities against Armenians, a claim seemingly based exclusively on his writings, but specific charges were never brought against him, nor did a trial ever take place; he was released after a prisoner exchange. With his native Azerbaijan now a part of the Soviet Union, he joined another Turkish cause, travelling to Ankara to support Atatürk in the War of Independence or National Struggle.

One of his first duties was to go to Kars on Turkey’s north-eastern border and use his journalistic ability to run his own newspaper and push back against anti-nationalist propaganda in Eastern Anatolia with propaganda of his own. His work was so effective that he soon received personal telegrams of thanks from Atatürk, and was promoted to Director-General of Press and Information before the end of the year. Returning to Ankara in late 1921, he took up new responsibilities in his role, becoming the manager of Turkey’s official state news service Anadolu Agency and continuing to publish articles furiously.

In 1923 Atatürk dissolved the Turkish National Assembly and personally picked Ağaoğlu to be a candidate in the elections. He duly won yet another seat, serving as the Deputy for Kars, this was the third and final national parliament he would sit in. During his parliamentary career, he would go on to contribute to the drafting of Turkey’s 1924 constitution. His relationship with Mustafa Kemal and the republican establishment was not always so cordial, however.

After finishing his term in office, Ağaoğlu went back to the Istanbul Darülfünün and started a new job as a law professor. As with his other jobs, this too did not prevent him from pursuing his journalistic passions. He founded a newspaper called Akın (The Torrent) in 1933, through which he publicly criticised Prime Minister İsmet İnönü’s government for its statism – Ağaoğlu himself believed that individualism, rather than the state was key to creating a modern society. The paper was swiftly shut down by the authorities, lasting less than a year.

His writing ruffled feathers in high places. One account even says he was confronted by Atatürk at a gathering. It is said that Atatürk subtly expressed displeasure at his publishing Akın. Ağaoğlu let him know that he would not close it down of his own accord, causing Atatürk to get angry and remind the Azeri that he was a refugee and not originally from Turkey (ironically Atatürk himself was not born within the borders of the Turkish Republic either).

CHP officials also berated him in parliament during his time in opposition, telling him to “speak Turkish” because of his Azeri accent. The same year that Akın was closed, Ağaoğlu also lost his job at the Darülfünün in a purge, which made way for the institution to re-open as Istanbul University.

In his retirement he continued to write in newspapers and journals on the issues of the day alongside cultural and historical subjects; he also wrote a book about Iran. In May 1939, Ağaoğlu died in Istanbul, leaving behind a monumental legacy.

By the time of his death, Ağaoğlu had served in three national parliaments, actively assisted in the foundation of two new countries, edited and written a vast corpus of literature in five languages (French, Farsi, Russian, Azeri and Turkish), promoted education across societies, and above all, had tirelessly worked for the betterment, protection and empowerment of his people.

The life of Ahmet Ağaoğlu is an embodiment of the well-known Turkish phrase that Turkey and Azerbaijan are “tek millet, iki devlet” – “one nation, two states.”

Those wishing to learn more about Ahmet Ağaoğlu and his life can do so by reading A. Holly Shissler’s book, Between Two Empires: Ahmet Agaoglu and the New Turkey, which was a major source for the content of this article.