Roots

The effects of the French Revolution in 1789 reached the Ottoman Empire nearly fifty years later. Starting from 1839 until 1876, during the regression period of Ottoman Empire, a set of reforms were implemented to modernise, centralise and improve the legal, economic, social and political structure of the government, which was called the Tanzimat Period.

These reforms, influenced heavily by Western-educated Sultans, helped reconcile Eastern and Western culture and also affected the cultural activities, which were mainly under the control of Ottoman intellectuals. The Ottomans started to put their own national stamp on the arts. For example, Giuseppe Donizetti Pasha was leading Daru’l-Elhan (House of Melodies / Istanbul University State Conservatory today) and played a significant role in introducing European music to Ottomans, inspiring them to compose their own hybrid of classical music.

The Tanzimat reforms were the underlying force behind the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. Turkish Folk music, for example, became more prominent through education and improving the technical skills of musicians, who were sent to Europe for education on a state scholarship and returned to the country as researchers, academics, and music teachers.

Community centres also played a big role in improving the Anatolian people’s cultural appreciation. A new modernised, polyphonic approach was adopted to preserve the roots and nature of the music, which finallybecame known as the “Anatolian sound”. Folk songs that were initially verbally composed and performed by Anatolian troubadours (aşık) in rural areas were notated and documented.

As contemporary Western music such as Jazz, Rock’n’Roll and Pop, took hold in mid 20thcentury Turkey, as in the rest of the world, the country’s biggest hits were all unique local works fostered by Anatolian culture.

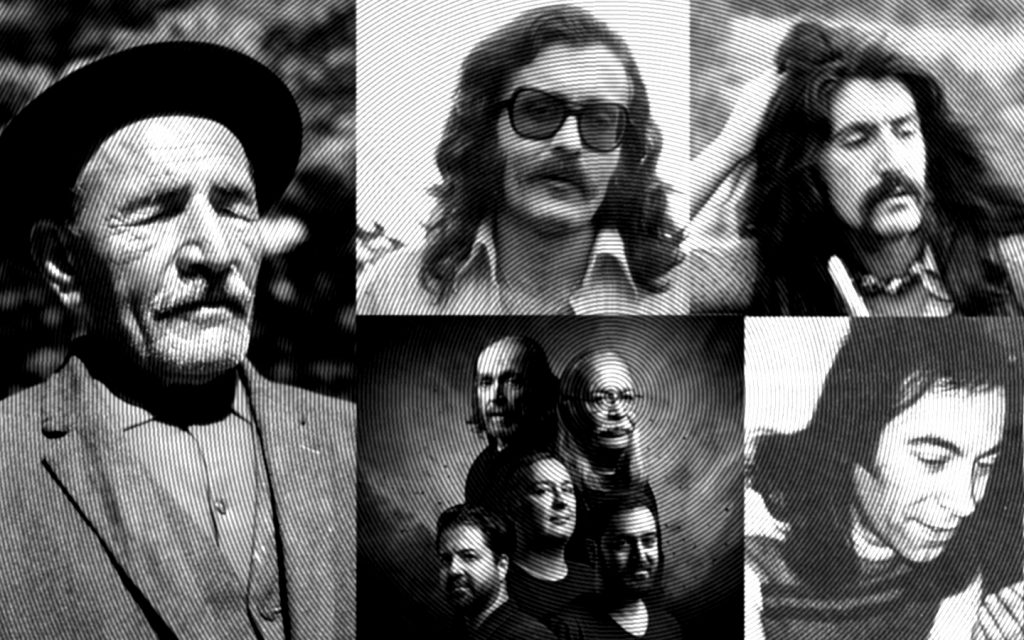

Aşık Veysel (Şatıroğlu), who was born in Sivas and lived between 1894 and 1973, was probably the most famous aşık in the country. He was a poet, songwriter and saz (bağlama) virtuoso. He was blind for most of his lifetime and his tunes were usually sad, and the lyrics were based on love, life, death, moral values and beliefs.

Another famous Folk musician was Aşık Mahzuni Şerif, who brought strong intellectual and social elements into Turkish folk music. He passed away in 2002. Ruhi Su and Neşet Ertaş were also among the Folk artists that influenced Anatolian Pop musicians over many generations.

Birth & Winter Sleep – Phase I

The term “Turkish Psychedelic” was invented by European music critics. The music was originally called ‘Anatolian Pop’ and later Anatolian Rock. During the late 60s, the hippie culture was dominating the music industry in America and Europe and the ‘Psychedelic’ genre was for bands such as Jefferson Airplane, 13th Floor Elevators, Iron Butterfly; most of the musicians were using LSD, inspiring the genre name, although this was not the case for the Turkish scene at the time.

It all started with the Altın Mikrofon (Golden Microphone) song contest that Turkish daily Hürriyet held in 1965. It aimed to promote popular original music with Turkish lyrics, instead of new artists merely doing covers of Western hits.

The contest, which ran between 1965 and 1968 and again in 1972, launched a new era and was a springboard for many Anatolian Pop/Rock musicians such as Cem Karaca, Erkin Koray, Sleek Alagöz and bands like Moğollar, Mavi Işıklar, Silüetler. Edip Akbayram won the last Altın Mikrofon.

The influence of Aşık culture on Anatolian Pop cannot be overstated. Many songs were inspired by Folk songs, with the new era artists visiting these Aşıks, so they could learn how to play the saz. The link could be observed in many artists’ songs and lyrics including Fikret Kızılok.

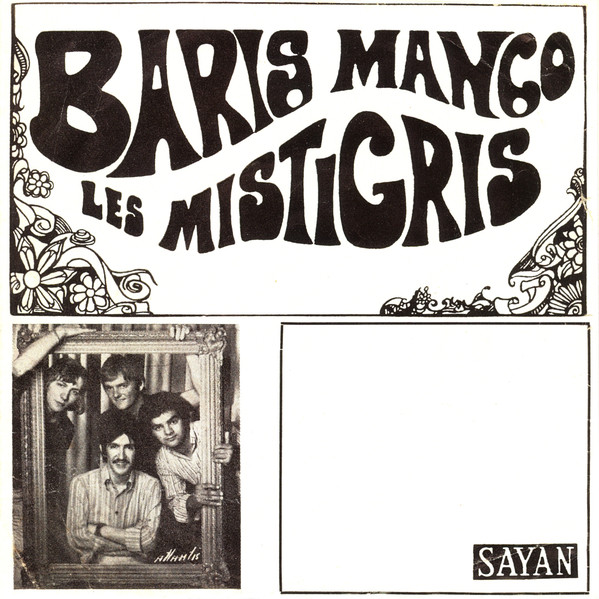

Moğollar were a hit in France: they signed a contract with CBS, released several singles and won a music award. Barış Manço found fame with a band called in Belgium. Welcomed with open arms for their overseas success when they returned to Turkey, these artists toured towns and cities across Turkey. However, their long-haired appearance and Western-influenced sounds drew criticism from conservative circles, who accused them of being ‘anarchists’ and ‘atheists’; yet it did not deter ordinary people from loving them.

The musical history of Turkey from 1965 until the coup in September 1980 is legendary and worthy of an entire book.

For young Turks especially, popular music became synonymous with leftist thinking and protests for greater equality, freedom, and workers’ rights. This was the era of the 68 Movement. Interestingly, many famous musicians were from highly intellectual Istanbul families with artistic backgrounds, with several attending the city’s prestigious French schools as children. The bands’ fans were ordinary middle and working class Anatolian people, who were politically conscious and attracted totheirlyrics and modern western sound.

The Resurrection – Phase II

A deep silence followed the coup d’état, and it took over a decade for freedom-screaming Turkish rock music to resurface. On the fringes, a punk, heavy metal and hard rock music scene emerged, but it was like a drop in the ocean given the huge popularity of Arabesque in the country during 80s.

All the quality music of the 70s was seemingly forgotten, like a quick format to a hard drive, but could not be completely erased. Yet itwas such a devastating memory loss that a new generation of rockers started discussing ‘if rock music could be composed with Turkish lyrics or not’ in the late 80s and early 90s, ignoring the massive history lying in the past.

During the dark ages of the military-controlled 1980s, many artists had to flee abroad, while others were imprisoned. With no chance of surviving in the music business, some abandoned their careers for other jobs or remained recording artists without touching political ground. Towards the end of the decade, some artists started performing live in small local concerts. But they were ignored by government-controlled mass media, ensuring their profile and voices were weak.

“Early heavy metal bands such as Pentagram turned their faces towards their own country, discovering rich layers of Anatolian music ripe for picking”

Cem Karaca had to stay in Germany for a long time and could not see his son grow up. He made albums in German and performed in the country. In one interview, he said he was ‘crying while looking towards the shores of western Turkey from Greek Islands’. When he braved a trip to Turkey and kissed the Prime Minister’s hand to show his respect, Karaca was heavily criticised by his early fans, but the star was then allowed to return permanently by the Turkish authorities.

In the spring of 1993, Moğollar made a welcome comeback with a huge concert in Istanbul after a magazine campaign urged their return. The following year, they released an album comprising new and old songs. One of the new tracks was dedicated to the artists killed in Sivas Massacre of July 1993. The lyrics of the album’s other songs also reflected the band’s political and environmentally-conscious stance.

The Rise – Phase III

Until the invention of publicly-available digital music, it was not easy to find or buy old cassettes or records. Vinyl factories had already shut down, and there was no great demand to buy old stuff to encourage a repressing.

Artists like Barış Manço, Erkin Koray and Cem Karaca and bands like Moğollar continued producing new albums, but the sound and content was markedly different to their recordings of the 70s. The analogue sound was replaced by keyboard-fuelled tunes, enhanced by electronic gadgets. Koray had ventured into Arabesque culture, while Manço was composing songs for children andproducing travel programmes for TRT.

The CD revolution lent itself well to a new wave of Turkish Pop and Rock music, driven by a new generation of artists. Early heavy metal bands such as Pentagram (Mezarkabul) turned their faces towards their own country, discovering rich layers of Anatolian music ripe for picking. Their 1997 album Anatolia included authentic Turkish instruments and Turkish lyrics, going against their own early albums andthe popular convention of Turkish bands singing in English.

After the advent of the internet, bands and the public had access to a vast archive of music newly digitized, which was shared on unregulated online platforms and downloaded freely. File-sharing applications became popular and this communal culture created awareness among a new generation of a musical treasure that had lain hidden for decades.

Although many international artists were furious about the illegal, free sharing of their music, that was costing them money, it sparked a rebirth of Anatolian Pop & Rock music.

Writers who had witnessed the era first time around, or had access to the artists, started to scribble articles and write books. With a resurgence in their popularity, fans old and new encouraged these iconic artists to produce new music.

Expansion – Phase IV

As US-based Turks Ahmet Ertegun, Arif Mardin and İlhan Mimaroğlu received international acclaim for their contributions to music, their influence was felt in Turkey too.

More foreign artists gave concerts in Turkey and this, coupled with the internet, meant the young generation enjoyed a boom in diverse music from around the world.

A ‘third eye’ helped Turkish musicians understand that to succeed abroad they needed to produce original material that drew on the unique sounds and culture of their homeland as much as contemporary music and technology. It was not dissimilar to the journey of their fathers’ generation in the late 60s & 70s, where Turkish instruments and the folk songs of Aşıks were recorded with Western arrangements.

In 2008, the movie Issız Adam (Lonely Man) by Çağan Irmak helped popularise record players. People flocked to flea markets and second hand stores hoping to buy records and a player, creating a resurgence of Turkish vinyl-hunting. Suddenly, not only Anatolian Rock, but Turkish music genres from classical to pop from the 70s and 80s became collectors’ items, with popularity driven by DJs, radio airplay and online playlists giving greater exposure to the sounds and artists of Anatolia.

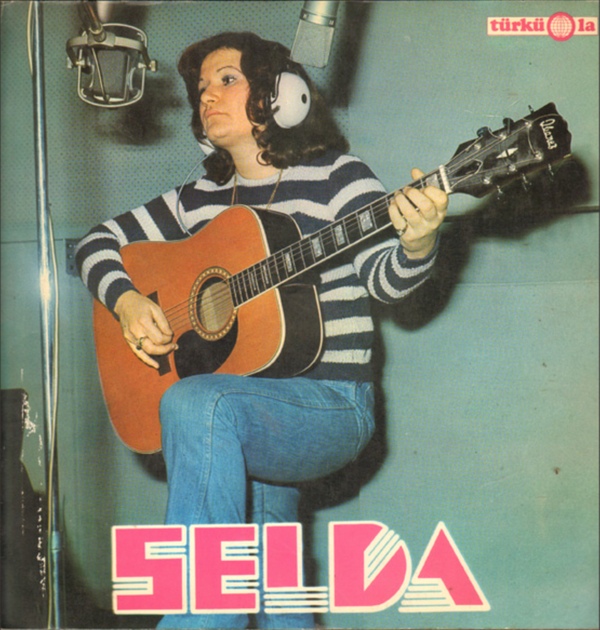

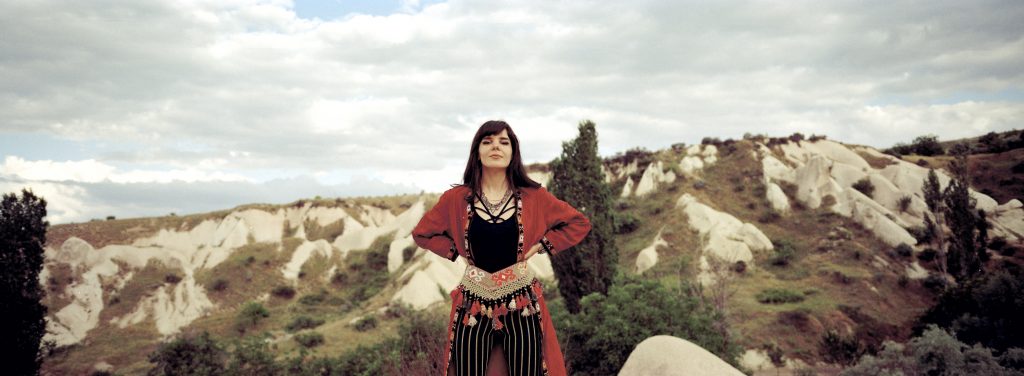

The music of Turkish Folk Rockstars became heavily sampled in the West. Selda Bağcan in particular saw her song İnce İnce sampled by Mos Def and Dr Dre among many others. Gaslamp Killer sampled Özdemir Erdoğan’s Gurbet (1972) on Nissim, while Erkin Koray’s Hayat Bir Teselli (1976) ended up on Klowds by GonjaSufi.

Leftfield underground Turkish bands such as BaBa ZuLa formed in the late 90s, producing soundtracks for films, performing in local clubs, and touring abroad. They became Turkey’s modern troubadours. Although influenced by the Anatolian heartland, their music was more progressive. The Replikas also paid homage to 70s Anatolian Rock, while carving out their own sound.

“Suddenly, Anatolian Rock from the 70s & 80s became collectors’ items, with popularity driven by DJs, radio airplay & online playlists giving greater exposure to the sounds & artists of Anatolia”

Talented new artists such as Gaye Su Akyol has gained international prominence, performing in major festivals. Turkish contemporary DJs such as Baris K, Kabus Kerim, Hey! Douglas, Kozmonotosman, Oceanvs Orientalis – pioneers of the Disco-Folk sound – are also fusing the melodies and songs of Anatolia in their electronic sets. Dutch-Turkish combo Altın Gün have excited crowds across Europe with their hybrid sound.

Before all of these came saxophonist İlhan Erşahin, of Wax Poetic and Nublu jazz club fame; his fluid Istanbul-inspired recordings had the instant cool factor. Mercan Dede (Arkin Allen) was also an important forerunner, with his electronic Sufi jams spawning many imitators.

The recent political and economic challenges across Turkey has also contributed to the rise of the country’s alternative music scene; an essential escape hatch from the grey clouds and depression hanging over young people. It came amid a backdrop of protests, and a host of concerts and cultural events cancelled due to terror attacks and even politics, at the whim of the Turkish authorities.

Those who could, who understood foreign languages, including artists, moved towards the West where art is an integral part of society. Many educated people and artists uprooted themselves from Turkey and migrated to Europe due to rising unemployment, a lack of freedom of thought and speech, and economic instability. With them travelled the sounds and archives of Turkish music.

Around 2009, during a visit to London, I was hunting for vinyl records in Soho when I heard a famous song by Erkin Koray. I approached the guy at the counter, asked him if he had that record. He said a Turkish friend had prepared him a mix CD, and he was also looking for the original record. It was great to hear that, though I was sad Koray’s LP was unavailable. A decade on, the British capital is awash with Turkish tunes in many unexpected places.

The term Turkish or Istanbul “Psychedelic’ has stuck internationally, defining the music of an era that has its roots in the Turkey of the 1960s and carries through to the present day. It is a blend of psychedelic, progressive, jazz, rock, electronica and Turkish folk with syncopated rhythms. It is stamped by the dedicated souls who forged a new musical path under tough circumstances in the country, and left us a huge legacy.

Today, record companies like Pharaway Records or Finders Keepers in Europe are releasing these Anatolian Pop and Rock stars’ records. New Turkish record labels and old ones, which are the remnants of Unkapanı (the former music district of Istanbul), are also re-releasing classic albums.

For many Turkish Anadolu Rock fans like myself, this is no passing fad; it is a fully-fledged passion, being shared and enjoyed by music lovers the world over. Popular artists from the 70s who are still alive are making new recordings and collaborating with other musicians, their status as icons and fathers of the genre fully established. The market is alive again, and there’s still a lot to discover and tell.