“All great transcendental art is not merely symbolic or imaginary: it is a direct invitation to recognize and realize a deeper dimension of our very own being,” wrote Ken Wilber in the foreword to The Mission of Art by Alex Grey.

And so it was with a stunning piece of performance art by Sumer Erek on Wednesday 4 November. His multi-disciplinary display comprised of paintings, live music, an installation and audience participation; a perfect blend of creative expression and spirituality that was fittingly hosted at Shacklewell Lane Mosque in Dalston, East London.

The mosque is hugely significant for me as a British Turkish Cypriot. It is the first Turkish-owned place of worship in Britain. The building was bought for the community by the late Turkish Cypriot businessman Ramadan Guney, and my dad (a qualified civil and structural engineer) designed the plans to convert the structure from a synagogue to a mosque, including its impressive dome.

All of my closest UK relatives, including my late mum, have made their final sacred journey from Shacklewell Lane Mosque too. So I always feel a deep affection for this beautiful house of worship, which under the chairmanship of Erkin Guney (the son of Ramadan Guney) has taken a more inclusive and progressive turn.

On 3 November, I received a call from Erkin informing me the mosque would host a special tribute to his mum Suheyla at the mosque. Suheyla teyze (aunty Suheyla) was a pillar of our community and founder member of the mosque, who tragically passed away on New Year’s Day in 1992.

The tribute was being created by Turkish Cypriot artist Sumer Erek, and would present aspects of Suheyla teyze’s life through art. I was intrigued.

I have known Sumer for over 20 years and everything he does is not only visually brilliant, but also intellectually thought-provoking. And his display at the mosque the following evening did not disappoint; indeed, it would be fair to say that I and the other people present were completely blown away.

Like everything else during London’s semi-lockdown, attending an art event is strange. We greet each other at a distance, wearing masks. Numbers indoors are strictly managed, and we remain apart.

We enter the mosque like regular worshippers, shoes off, modest clothes on. Some have head coverings, others not – Erkin’s global outlook is driven by love, so he welcomes all, Muslims and non-Muslims alike, as long as they show respect.

In the centre of the mosque Sumer has planted a tree – the essence of life and Mother Nature. Assembled around it are musicians – a random assortment of British and foreign players performing light mood music for the evening. They include a drummer, guitarist, and players on double bass, trombone, and kanun (stringed instrument).

Forming a loose circle around them are stacks of cassettes, the remnants of Suheyla teyze’s legendary Müzik Dünyası music shop on 58 Green Lanes, Newington Green, N16, which every Turk in London would have visited in the 1970s and 80s to pick up Turkish music of every conceivable genre, and videos of classic and current Turkish films.

At the back of the mosque, propped up against the lockers, are large and small portrait paintings of Suheyla teyze, with leafs beneath and around the picture frames.

We sit, socially distant, some on chairs, others on the floor, listening to the music, which carries us to different places.

At some point, Sumer asked some of us to take a painting and place it by the tree. Most of us walk solemnly, delicately weaving our way through the cassette columns and musicians to find a snug space to plant our painting. I said a silent prayer to Suheyla teyze after doing so. One lady gently waltzed through the maze, gazing lovingly at Suheyla teyze’s face.

After this moving tribute, we sat back to listen to the music. Murmur-like at first, but growing into a crescendo we heard a delightful voice repeatedly sing the word “Suheyla”. Other words followed, mostly in Arabic, but some in Turkish and English. It was hypnotic and profound at the same time. Erkin was in tears.

The musical arrangements were so good, you’d think the band had practiced this for ages, but Sumer later told me that most of the musicians had only heard about the event the night before and their performance was entirely improvisation.

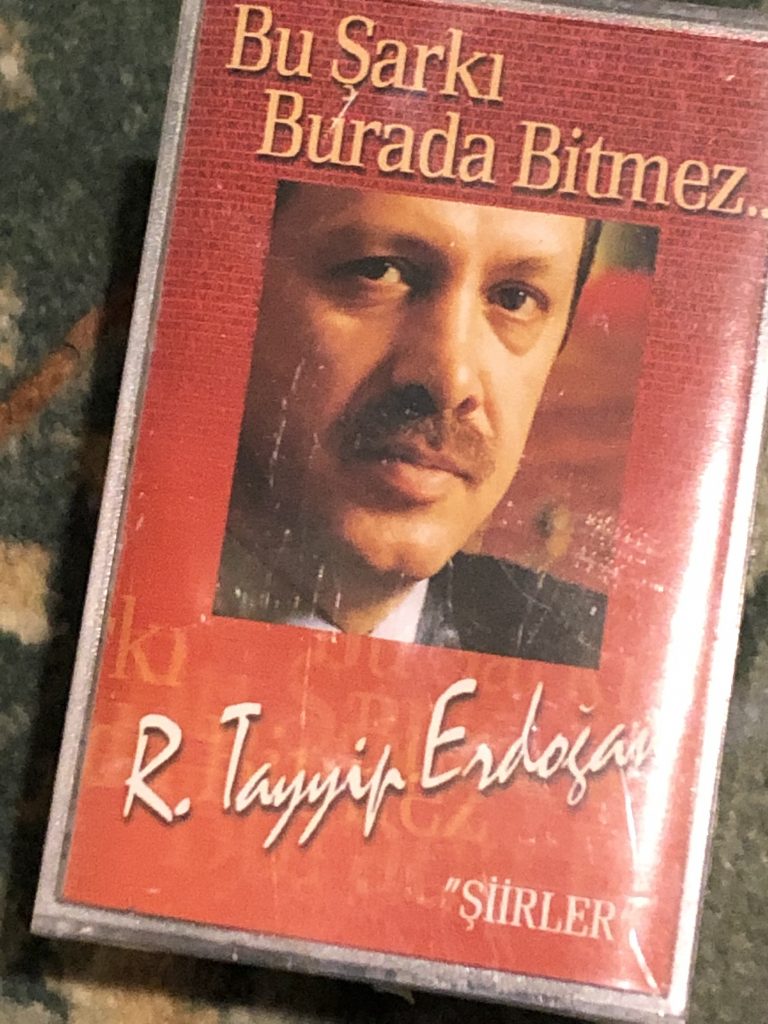

When the music stopped, one musician came and showed us a tape he’d found among the huge collection. ‘Bu Şarkı Burada Bitmez’ [This Song Doesn’t End Here’] by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The recording – mostly poems he recited and one song – was released in 1999, just before he went to jail. The discovery and the album title added to the already surreal experience we are having.

A lady came and thanked Erkin for allowing her to be present for such a ‘personal and incredible’ tribute. She told us she was of Kurdish Alevi heritage, and was in total awe at what she had witnessed. She was struggling to comprehend the progressive nature of Shacklewell Lane Mosque, and was struck by the warm welcome each of the diverse guests had received, including herself. She said had never in her life expected to see such a cultural display in a mosque.

Mosques are normally a taboo space for Alevis. Their own house of worship – the cemevi – offers a very different devotional experience to that practiced by Sunni Muslims. Music and dance feature in Alevi worship, and men and women pray together.

I explained to the lady most Turkish Cypriots are traditionally relaxed about their faith. Living on an island where multiple religions and ethnic groups have co-existed for centuries is one reason. Another is that Ottoman Alevis, Sufis, and Sunni Muslims all moved to Cyprus following the Ottoman conquest of the island in 1570-71, so our experience of Islam has no doubt evolved differently, and included a fair bit of mysticism too.

At the end of the performance, there was a real feelgood factor about Sumer’s event and a palpable buzz as we left the mosque. All the components had flowed together beautifully, transcending boundaries of faith, ethnicity, and even pandemic fears and frustrations (the following day would be the start of four weeks of lockdown in London).

For those of us from a Turkish Cypriot background, this wonderful homage to Suheyla teyze’s life, reminding us of her love of music and place in our community’s history made us yearn for more such stories.

Sumer’s choice of artistic expression offers such an evocative way of telling both personal and universal tales; it’s exciting to note he plans more performances that will pay tribute to other British Turkish Cypriots, again fusing aspects of their lives with our culture, re-told through art.

Turkish Cypriots have been in Britain for a century, and as our community history and narrative evolves, it’s important we don’t forget our roots, experiences and traditions.

As Nigerian writer Ben Okri wisely noted, “Stories are the secret reservoir of values: change the stories individuals or nations live by and tell themselves, and you change the individuals and nations.”