Last Friday the world laid Muhammad Ali to rest. The 74-year-old former boxing heavyweight champion died on 3 June after being admitted into hospital in Phoenix, Arizona, with respiratory problems aggravated by his Parkinson’s disease.

Ali’s passing was mourned worldwide, his larger-than-life personality having transcended his sport to make him one of the most iconic and adored figures in our lifetime.

Media outlets globally, including those in Turkey and the TRNC, were dominated by his death, celebrating his life in pictures and famous Ali quotes, while recalling his considerable achievements.

Turks of all backgrounds also paid their respects to the charismatic Ali, who was simply known as The Greatest. Turkish Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım offered his condolences to the Ali family:

“We are deeply saddened by the passing of Muhammad Ali who became a symbol for people fighting injustice and unfairness, and those who were marginalised due to their skin colour and beliefs”.

Seyfullah Dumlupinar, Turkey’s 48-year-old national boxing coach, told Anadolu News Agency he had been inundated with calls from the boxing community grieving over Ali’s death. He described the loss of one of the most influential sporting figures: “Boxing lost its father and idol. Because of Ali, many people became boxers and Muslims.”

“Boxing lost its father and idol. Because of Ali, many people became boxers and Muslims.”

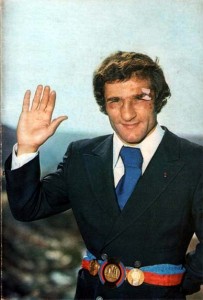

Many other Turks recalled their memories of the great boxer and civil rights activist, among them Cemal Kamacı. The former European champion’s career spanned roughly the same period as Ali’s.

After winning his European Super Lightweight title, the Turkish boxer travelled to the US, where he met Ali during a visit to his training camp at a gym in Madison Square Garden and the two worked out together. Kamacı, now aged 73, told Al Jazeera:

“When he [Ali] learned that I was Turkish and a Muslim, he hugged me…He was a respectable, shining human being. When you say boxing, Muhhammad Ali is always the first name to spring to mind.”

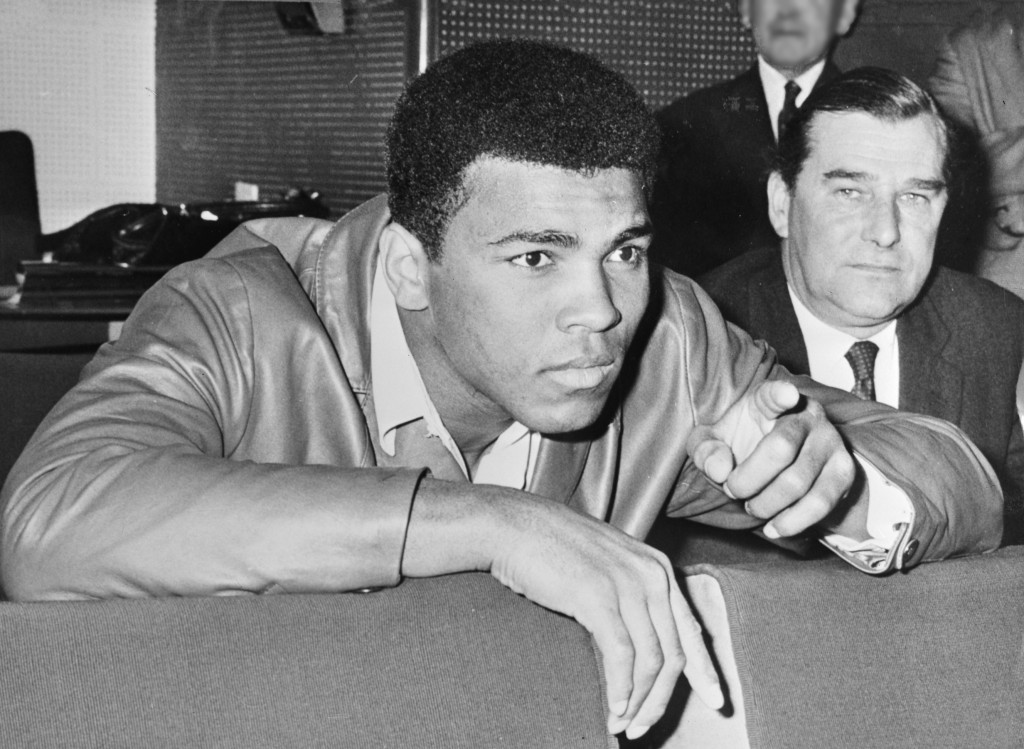

My father, Oktay Hamit, a retired civil engineer, recalled how he met Ali as a student in London during the mid 1960s.

“I never used to like boxing, but when Ali became champion, I was hooked. It was the way he was so confident: he would say he was going to win and then he did! I would stay up late just to watch his fights.”

“I met him briefly twice, while I was working in the Wimpy Bar in Piccadilly [Circus]. The first time he came in, he was still Cassius Clay. He turned up with a few people and everyone was in awe. The Jamaicans (co-workers) were ecstatic!”

“He was a big fellow and very friendly, always smiling. He gave autographs to everyone who asked: on napkins, papers – anything he could write on. I told him I was a big fan and he shook my hand. And then, some years later, he came [to the Wimpy Bar] again and we shook hands again.”

“When he [Ali] learned that I was Turkish and a Muslim, he hugged me…

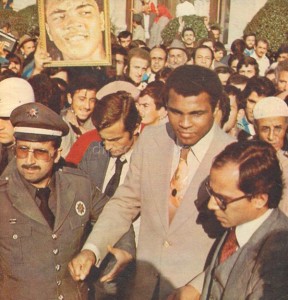

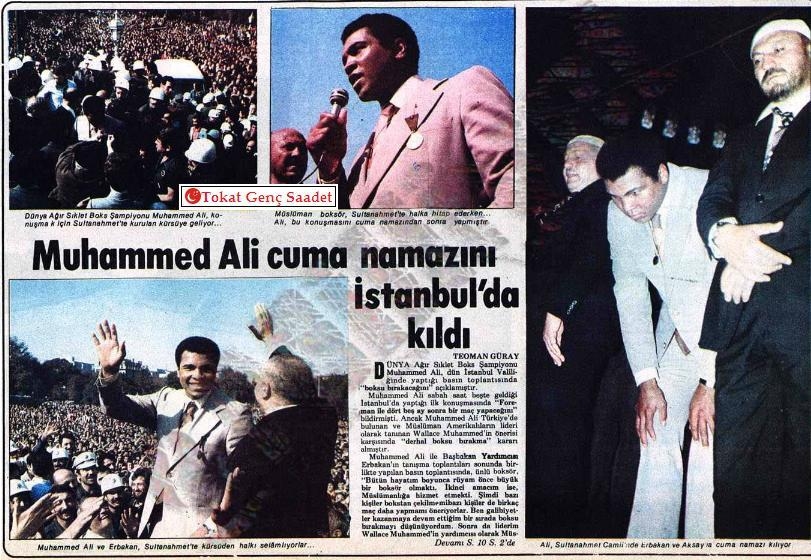

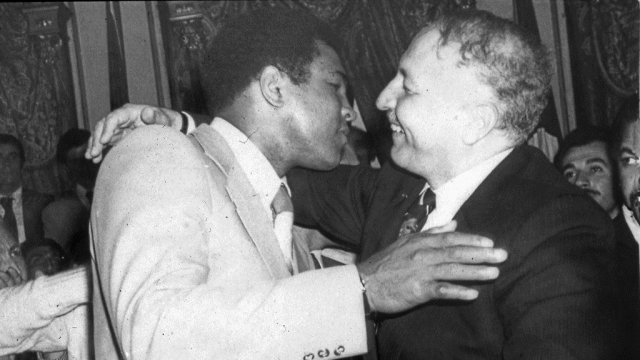

In 1976, the boxing legend visited Istanbul after receiving an invitation from Kemal Baytaş, the Deputy Undersecretary for Turkey’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

Necmettin Erbakan, then Deputy Prime Minister, greeted Muhammad Ali at Atatürk airport. Together they attended Friday prayers at the historic Sultan Ahmet Mosque and toured Haghia Sophia as thousands of fans lined the streets to catch a glimpse of their hero.

Ali was already committed to fighting racism and injustice. In his speech in Istanbul, he said he would also serve Islam once he retired from boxing, further endearing him to devout Turks, many of whom felt marginalised by Turkey’s secular state.

According to legend during that first 24-hour visit to Istanbul, Ali told Erbakan: “No white leader ever embraced me before.”

In later interviews, Ali would repeat how Muslim leaders and royalty had warmly welcomed him, yet in his own country he had been repeatedly shunned due to the colour of his skin and his political views.

The respect between the two men was clearly mutual: in 1979, Erbakan named his only son Muhammad Ali Fatih.

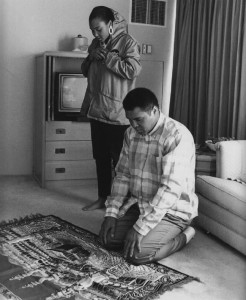

Another Turk, Dr. Nevzat Yalçıntaş, was said to have helped the boxer to learn how to pray like a Muslim. In media interviews, Yalçıntaş explained that he was based at the London Islamic Centre when Ali – then still Clay – visited the centre in 1963 and announced he was planning to convert to Islam. Yalçıntaş was asked to guide Ali.

The two reconnected thirty years later, when Yalçıntaş arranged for Ali’s second and final visit to Turkey. The retired boxer was a special guest at the opening ceremony of new national TV channel TGRT in Istanbul in 1993.

Who was Muhammad Ali?

He was born in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1942 and named Cassius Marcellus Clay, Jr. after a slave trade abolitionist. While the slave trade era was over, segregation and discrimination against America’s black population remained intact, especially in the region known as the ‘Slave states’ where Clay grew up.

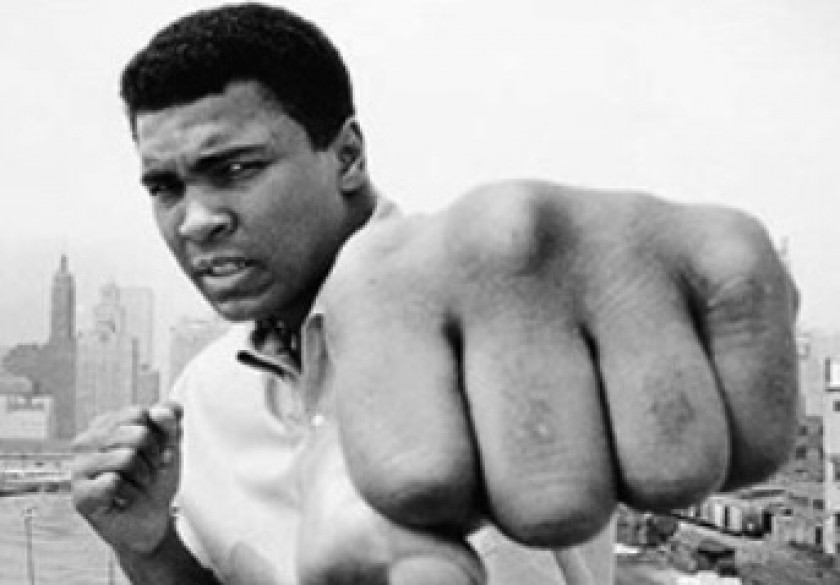

He first put on a pair of gloves aged 12. Six years later, with numerous amateur boxing titles under his belt, Clay was selected by the US Boxing Team to compete at the 1960 Rome Olympics, where he won a gold medal as a Light Heavyweight.

Yet even as an Olympic champion, Ali could not get served at a racist restaurant in his home town. He used his fame to highlight this and many other issues he and other oppressed people faced.

Within months of winning at the Olympics, and with an amateur boxing record of 100 wins and 5 defeats, Clay decided to turn pro. Four years later, he was crowned heavyweight champion of the world after knocking out Sonny Liston in 1964.

On Sonny Liston: “After I beat him I’m going to donate him to the zoo”

In the build-up to the fight, the fearless Clay captured attention with what would be trademark taunts of his opponent. At 6ft 5in, Liston was a huge fighter and widely regarded as unbeatable. Ali seized on his nickname, The Big Bear, instead calling Liston “the big ugly bear”, who “even smells like a bear”, adding, “After I beat him I’m going to donate him to the zoo.”

Following his victory, Ali danced around the ring and cried out: “I’m the King of the World! King of the World!”

Within weeks of becoming world champion, Clay converted to Islam and took a new name: Muhammad Ali, given to him by Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam. When questioned by the media and public about his conversion, Ali would explain that Islam resonated deeply with him and he admired the religion for embracing diverse people of colour as equals.

Influenced by the teachings of the Nation of Islam, Ali also spoke out against American involvement in Vietnam. He refused conscription into the American army as a Muslim and a conscientious objector, stating:

On Vietnam: “My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother”

“My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people or some poor, hungry people in the mud, for big, powerful America. And shoot them for what? They never called me nigger. They never lynched me. They didn’t put no dogs on me. They didn’t rob me of my nationality, and rape and kill my mother and father. Why would I want to—shoot them for what? I got to go shoot them, those little poor little black people, little babies and children, women; how can I shoot them poor people? Just take me to jail.”

Ali’s stance against the American government was deemed ‘provocative’ and resulted in him being sentenced to five years in jail, which he never served. However, he was also stripped of his title and boxing licence, preventing Ali from fighting between March 1967 and October 1970 – the prime years of his career.

Although vilified for his views, Ali refused to bow down and instead challenged the court’s decision, taking his case all the way up to the Supreme Court, which finally overturned the verdict and ended his professional exile.

Soon after returning to the ring, Ali experienced his first professional defeat during an epic 15-round contest against Joe Frazier in 1971. But Ali bounced back: a series of wins demonstrated the champ was on form, yet his career nearly came to an end in a fight against Ken Norton who broke Ali’s jaw in 1973.

Before Rumble in the Jungle: “I’m so mean I make medicine sick”

He recovered and went on to become heavyweight champion again, in two thrilling title fights against George Foreman: Rumble in the Jungle (1974, Zaire) and Thrilla in Manilla (1975, Philippines).

![By John H. White, 1945-, Photographer (NARA record: 4002141) (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.t-vine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/WORLD_HEAVYWEIGHT_BOXING_CHAMPION_MUHAMMAD_ALI_A_BLACK_MUSLIM_ATTENDS_THE_SECTS_SERVICE_TO_HEAR_ELIJAH_MUHAMMAD..._-_NARA_-_556247-1024x695.jpg)

Ali’s bravado knew no bounds. He told TV presenter David Frost: “If you think the world was surprised when Nixon resigned, wait ’til I whup Foreman’s behind!”

In a press conference in Zaire before ‘Rumble in the Jungle’, he said, “I’ve done something new for this fight. I done wrestled with an alligator, I done tussled with a whale; handcuffed lightning, thrown thunder in jail; only last week, I murdered a rock, injured a stone, hospitalized a brick; I’m so mean I make medicine sick.”

“Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee”

The public lapped it all up, as much for Ali’s entertaining ways as for his undoubted boxing abilities. Unusually for a heavyweight, Ali relied not just on brute power, but – like his catchphrase “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” – on speed, lightning-fast reflexes and the constant movement around his opponents. It was electrifying to watch.

A three times world heavyweight champion and Olympic gold medallist, Ali is widely regarded as one of the greatest heavyweights in the history of boxing. When he finally hung up his gloves in 1981, he had recorded 56 wins, including 37 knockouts, against five defeats.

Yet his legacy outside of the ring remains equally enduring. He gave a voice to the poor, the racially discriminated and to Muslims worldwide.

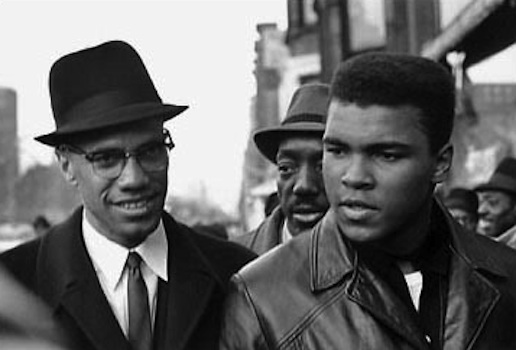

In his diary, fellow Muslim and civil rights activist Malcolm X noted that Egyptians and Saudis repeatedly mistook him for Muhammad Ali during a five-week tour of the region in 1964.

“The Muslim world,” Malcolm wrote, was so enamoured of the boxer that “even the children know of him.”

The following decade, Ali decided to move away from the Nation of Islam, instead adopting the more mainstream Sunni branch of Islam in 1974, and Sufism in 2005. He continued to speak out against events that concerned him, from injustice to Islamophobia and terrorism.

‘Ambassador for peace’, Ali helped free 15 American hostages in Iraq

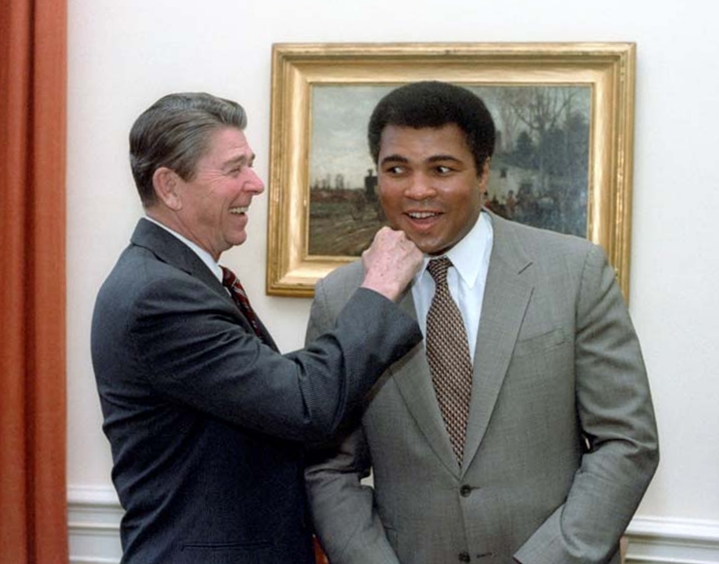

After retiring from the ring, Ali was determined to use his high profile to work as a peace ambassador. Perhaps lesser-known in his long list of achievements are his efforts to act as a bridge between America and those forces and nations hostile to the USA.

In 1985 he flew to Lebanon to try and free four American hostages. He also made goodwill missions to Afghanistan and North Korea, and delivered medical aid to Cuba.

Ali’s intervention resulted in the freedom of 15 Americans taken hostage by Saddam Hussein during the run-up to the Gulf War. Although initially heavily criticised by Washington, Ali flew to Baghdad in November 1990 on a mission the White House dubbed “loose cannon diplomacy”, in a bid to secure the release of civilians being used as human shields in buildings Saddam thought the Americans could bomb.

After a week in the city, where he’d gone on walkabout, regularly being mobbed by Iraqi fans, Ali ran out of his Parkinson’s medicines and could barely move. His aides managed to track down emergency supplies via the Irish Hospital in Baghdad as they waited to see if the Iraqi leader would meet with America’s most famous Muslim. A day later, they were told Saddam would talk to him.

The meeting was held in front of the media. Ali promised to tell America an honest account of the situation in the Gulf. Saddam replied, “I’m not going to let Muhammad Ali return to the US without having a number of the American citizens accompanying him.”

On Dec. 2 1990, Ali and the 15 American hostages flew out of Baghdad and returned to JFK airport in New York.

Ali maintained a strong interest in current affairs at home and abroad, and would regularly speak out on matters he cared about. In response to a wave of attacks by Islamic extremists, Ali issued a statement last December condemning the killers:

“I am a Muslim and there is nothing Islamic about killing innocent people in Paris, San Bernardino, or anywhere else in the world. True Muslims know that the ruthless violence of so called Islamic Jihadists goes against the very tenets of our religion.”

In 1984, Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Over the years he did his best to resist this debilitating illness, yet it turned this once towering figure into an increasingly frail man.

Following news of his death a fortnight ago, tributes poured in from around the world. Fellow boxer Foreman said Ali was, “One of the greatest human beings”, while US President Barack Obama, who keeps a pair of Ali’s gloves in the White House beneath a picture of Ali after he’d beaten Sonny Liston, said: “Muhammad Ali shook up the world. And the world is better for it.”

He was married four times and had seven daughters – two by extra-marital relationships – and two sons.

Ali: “He who is not courageous enough to take risks will accomplish nothing in life.”

His funeral was held in Louisville – the city he grew up in. The first part was an Islamic service – cenaze – at the Muhammad Ali Centre. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Yusuf Islam (formerly Cat Stevens) helped carry Ali’s coffin into the main hall. Turkey’s Grand Mufti Mehmet Görmez also attended.

The second part was a memorial service at the nearby KFC-Yum Sports Arena, named after Kentucky’s second favourite son, Colonel Sanders. Former US President Clinton, actors Billy Crystal and Will Smith, and a host of former boxing champions were among those present, alongside Ali’s family and friends, and those members of the public lucky enough to gain access.

The event, televised live globally, saw many speak about their memories of the great man. One of the most moving eulogies came from Attallah Shabazz, daughter of Malcolm X, who quoted Ali:

“We all have the same God, we just serve him differently. Rivers, lakes, ponds, streams, oceans all have different names but they all contain water. So do religions have different names and yet they all contain truth. Truth expressed in different ways and forms and times. Doesn’t matter whether you’re a Muslim, a Christian or a Jew. When you believe in God, you should believe all people are part of one family. For if you love God, you can’t love only some of his children.”

Malcolm X had been one of Ali’s early mentors. However, the boxer decided to turn away from his inflammatory, separatist rhetoric and ideas. Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965. Years later, Ali sought out his daughter that he’d first met when she was a little girl. The bond between Ali and Attallah Shabazz has remained strong ever since. She acknowledged the importance of Ali’s legacy in her speech:

“When you are in the presence of someone whose life is filled with principle the seed is in you, so you have to cultivate that responsibly, as well…His words and certainly ideals, shared by both men [Ali and Malcolm X]. Love is a mighty thing. Devotion is a mighty thing. And truth always reigns.”

She ended by saying, “My dad [Malcolm X] would often state when concluding or parting from one another: ‘May we meet again in the light of understanding.’ And I say to you with the light of that compass, by any means necessary.”

Ali came from humble beginnings and was determined to become a ‘somebody’. Life was not easy for a Black man in segregated America – a situation many in Turkey, North Cyprus and throughout the world can relate to – yet he overcame to become The Greatest.

One of his most memorable quotes was: “He who is not courageous enough to take risks will accomplish nothing in life.”

The People’s Champion talked the talk and walked the walk. His legend spoke to us all, inspiring us to dream and aim high, to say what we think, to stand up for what we believe in and to be prepared to fight for it.

We will most probably never see another like him in our lifetime. May he rest in eternal peace.