“Life is the absoluteness of truth which exists in its own essence.”

-Osman Türkay-

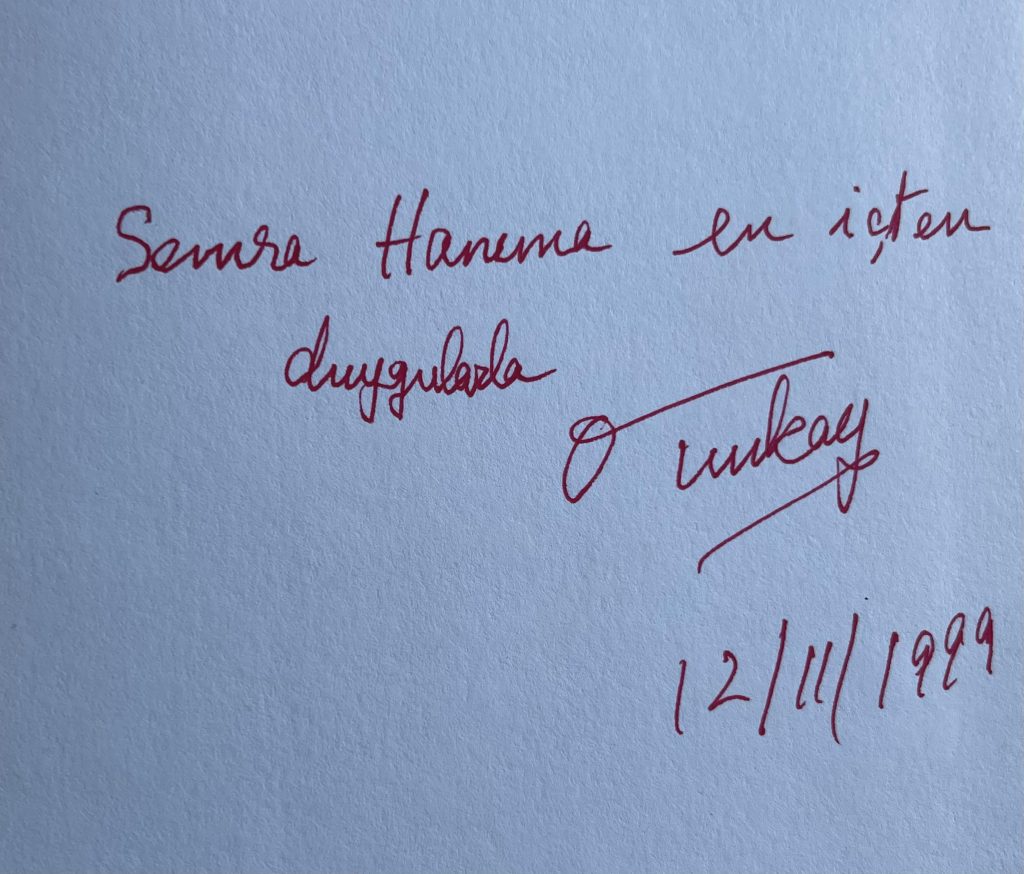

I cannot describe my joy when I stumbled across a cassette, which I had been looking for many years and finally found during some building works at home. It was the tape with a recording of an interview with Osman Turkey that I had conducted over 23 years ago, on 12 November 1999 to be exact, and another interview conducted with Mustafa Gençsoy on Osman Türkay in 2012.

The day I visited Osman Türkay, I interviewed him in depth, but I had only used a short version of that interview for my ‘Turks in London – The Unheard Voices’ exhibition in 2006, that was displayed at City Hall – the home of the Greater London Authority, and subsequently in 2007 at the European Parliament in Brussels, along with other biographies I had collated.

I intended to transcribe the interview fully in 2010. Unfortunately, I misplaced the tape in my storage boxes and failed to find it. I knew over time, each word of this great poet and thinker would gain even more weight and it would become more significant over time. As I started to transcribe the tape, it felt as if I had conducted this interview very recently, that it is timeless.

The transcribed interview below is not only an opportunity to revisit our past and talk about our heritage, but also a piece about the great Turkish Cypriot writer and Millennium poet Osman Türkay.

Osman Türkay’s thoughts in this interview particularly shed light on the work of people who committed themselves to the work of Turkish community organisations in the UK.

Building on this is the other transcribed interview with Mustafa Gençsoy about Osman Türkay, which will be published in Turkish in the near future.

Background about Osman Türkay and our 1999 interview

Osman Türkay’s poems have been translated into more than twenty languages and he was twice nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature, once in 1988 and again in 1990. His work has been accredited with many honours and recognised for its rich contribution to the world of literature internationally.

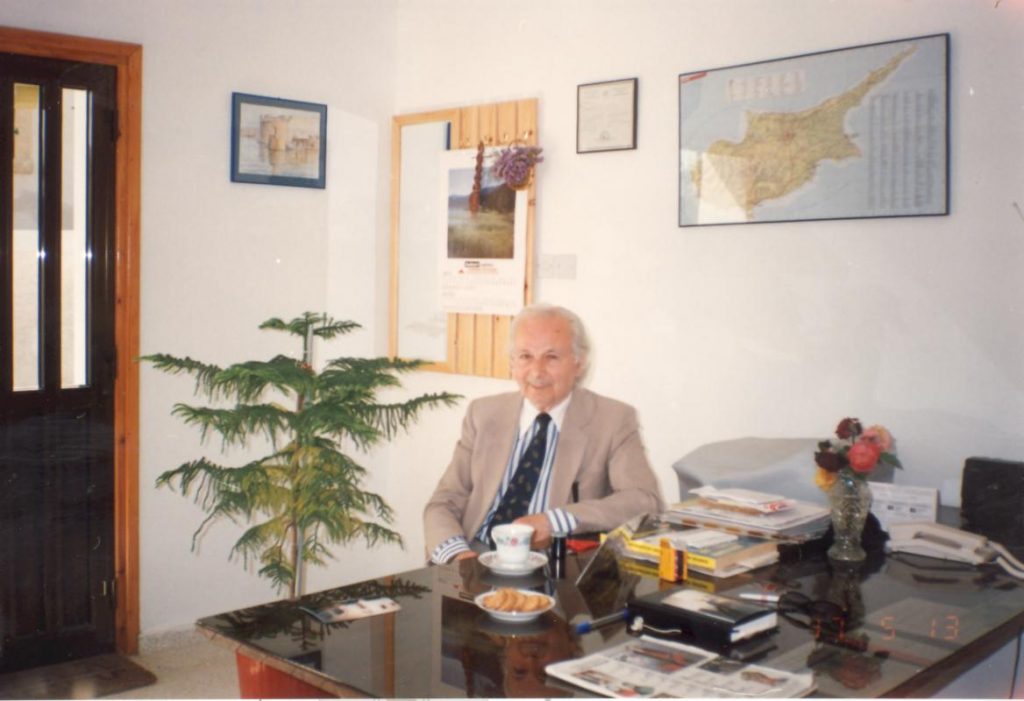

Osman Türkay was waiting for me when I arrived at his office at the top floor of Kıbrıs Türk Cemiyeti or the Cyprus Turkish Association’s building on D’Arblay Street, Soho, London, that day. He greeted me with a warm smile and, after asking me how my journey was, he offered me a slice of mandarin he was peeling, and then we began with the interview.

Interview transcript

Osman Bey, you were born in Girne, Cyprus. Which schools did you attend before you came to London?

I was born in 1927 in Girne, Cyprus, in the village which is now named after me, ‘Ozanköy’ [Turkish for Poet’s Village’].

My father was a small landowner. I went to the local English High School in Cyprus and graduated in 1946.

My poetry journey started when I was still very young. I was very passionate about poetry and started writing poems at the age of 14.

When did you first come to London?

From 1947-1953, I worked in the local newspaper as a columnist and as an assistant editor. However, between these years I also worked as a translator for NATO at the Incirlik Air Base in Adana, Turkiye, which opened in 1951. I came to London in 1953.

You were working as a professional journalist in Cyprus. What did you do when you came to London?

Yes, although I was working as a professional journalist and practising journalism in Cyprus, my dream was always to study journalism. And soon after my arrival in London, I enrolled myself at the London Polytechnic to study journalism and graduated in 1955. During that time, I also studied philosophy, which I always had an interest in.

You worked not only as a journalist, but also as a translator, and you have translated famous poets like T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Dylan Thomas, Neruda and Mayakovski into Turkish, is that right?

Yes, all my life I worked as a translator and as a journalist. I have translated the works and poetry of those poets that were my preferences and favourites.

It looks like you have translated poems from a wide spectrum, politically diverse, [both] the political left and right-oriented poets.

For me the world of literature is the crossroad to humanity, therefore I do not make any distinction.

After finishing your studies, you returned once again to Cyprus.

In 1958, I returned to Cyprus and continued to work as a journalist for newspapers and magazines. I also worked as a member of the [island’s} Turkish Consultative Assembly.

Interestingly, sometime later you decided again to leave Cyprus and return to live in London for good. Can you tell us why?

I decided to come to live in London as there was nearly no community of artists and writers, who were actively involved in either the area of arts, literature or writing in Cyprus.

I left Cyprus with the hope that I would one day return and live there.

Again, I left Cyprus as a poet to continue with my writings and my passion for literature and poetry. I needed the nourishment from the world of art, as it was particularly important for me.

On your arrival you got deeply heavily involved with the Cyprus Turkish Association (CTA), which was established in 1951, and became very active. Can you explain why was it important for you to become active within that association?

First of all, I knew teaching Turkish was very crucial and important. One’s mother tongue is the base of everything in life and, also, the key for a successful life in Britain, and therefore I became involved with the education of Turkish children, teaching their mother tongue in London. We had to be there for the members of the CTA who were new to Britain.

Turkiye’s Education Ministry must have realised as well that the teaching of the mother tongue was important. Is that why they started sending teachers to Britain?

Yes, Turkiye initially sent one or two teachers at the beginning, but later the numbers of the teachers increased as we got involved in teaching Turkish in several London schools.

Whilst it was important to teach the mother tongue to Turkish children, we were also thinking at the same time to provide support and education in order for them not to lose their Turkish identity. We knew if the children from Turkiye or Cyprus received a good education from a very young age, they would value and understand their heritage, and this would help develop their identity positively.

Without doubt not only teaching the Turkish language to children, but also teaching them about their heritage was one of CTA’s main objectives.

We can say that myself, along, with others who were involved with the work of CTA were thinking of providing education specially to support their Turkish identity.

Did you have any plans or ideas on how to achieve at that time?

Well, I always admire the work ethic of the Jewish community. The education they were providing for their children was a very good example for us.

The community took education very seriously and were providing a good programme from different areas like the arts, politics, science, economics, and sport.

Turks have only opened themselves up after the Second World War. If Turks wish to take part, participate and be successful in the 21st Century, we have to take a cultural approach and a positive work ethic, like the Jewish community. We can learn a lot from them and progress.

However, Judaism is a religion. Jewish people can be part of society or nation anywhere in the world and practise their religious beliefs. When we talk about Turks, we talk about a nation. We have to make a distinction between national and religious identity.

Yes, I agree. We have to be careful and make the distinction. But we should learn how the Jewish community teach their children Hebrew. How successfully they run their schools and how they provide their community with a sense of belonging to their religion, while integrating within the wider society in which they live. We can learn all this from the Jewish community very positively.

I understand, you believe people living away from their country of origin or from their parents’ country of origin must get organised and be involved with community work.

Indeed, it is very important to be active in community organisations or associations. I have been a member of the Cyprus Turkish Association for the last 30 years and I have taken part in almost all of their activities, including from editing the newsletter to outdoor activities. And, as mentioned before, I was teaching Turkish to children and setting up Turkish schools.

Community organisations and associations are for the migrants to get together and to network with each other. Those associations are often a mixture of folkloric and scientific practices, and have the foundation in the community to mobilise on any issue of interest. Getting organised around those associations or organisations is the most sensible thing to do when people have migrated to a different country.

But don’t you think there is also a risk of fading away from the wider British society if a community gets involved too much with the politics and events of the country of origin or of their parents’ country of origin? Striking a balance is important. What is your opinion on that? How should the balance be preserved?

When we came to this country from Cyprus in the 1940’s – of course Cypriots arrived also at the beginning of 1910’s – there were only a handful of Turks, Cypriot Turks. We had to do everything from scratch. And this was not easy. My generation worked non-stop, and very hard, and this manifested into the positive contributions they made to the wider British society.

However, on arrival, the Cypriots had the need to gather closely, to stay together and, on many occasions, to work together.

Although Cyprus was a former colony of Britain and a Commonwealth country and, also, people from Cyprus were acquainted with the British system, many things were still very new, different, and strange for the Turkish Cypriots in Britain. Consciously or unconsciously, they wanted to stay close to each other, in order to be strong and confident.

Is it not the case that they did not have anywhere to go and socialise among each other, so they were meeting interestingly in Trafalgar Square, and they used to call the place “Güvercinlik” which means the ‘place of pigeons’?

Yes, it was also a place where many people used to go and take photos when they first arrived in this country. And it is important to mention, as you would know as well, this reality of the difficult time applies to all communities which settle in a new country. This is the blunt reality of migration.

Do you think the younger generation of the UK Turkish Cypriot Community will continue to be interested and continue with the work in the community of their parents and grandparents in the future?

Within their own right the younger generations might move away from the work of the association or might not like to be involved as they will feel more part of mainstream British society.

The well-educated, well informed, professional people or the leaders in the community must revise their practices and develop new approaches to get them involved.

They must get the younger generation involved by listening to them and getting advice from them. This is the only way to get them involved in community work.

The professionalism of the third, fourth and fifth generation of Turks living in Britain should be taken into account, while getting organised in those areas which affect the community and [so they can] prosper together in British society.

They will be the best model for the future; older generations have to follow and listen to them. As the founder of the Turkish Republic Ataturk said, “The future belongs to the youth”.

What would you like to say about prejudice or racism? Do you think racism is a reality in Britain?

I cannot say that British people are racist. They are selfish. They are very selfish. If an ordinary man travels to his work by public transport in London, of course he may get annoyed by the number of foreign visitors to the capital and his lack of comfort as a result of no seat to rest while travelling. They only think of themselves and are very self-centred.

Would you say that is beyond or a step too far in self-regarding?

Believe me, in many other countries around the world, any ordinary man travelling to work and not getting a seat, will behave in the same selfish manner as the white British man in Britain.

Of course, when the economy is prosperous and things around the country look satisfactory, prejudice and exclusion is not highly prevalent. Only when the economic situation is unsatisfactory then the foreigners become visible and a target of all ills of the society.

As a person who has been involved in politics for the last two decades, what would you like to say about the Turkiye-UK relationship?

British people are sympathetic towards Turks in general and Britain always acts in its own economic interest and strategic needs. That is my observation in general. For example, when the Turkish and British Government get particularly involved in trade, the relationship significantly flourishes.

Does it mean as long as Turkiye can be a partner for Britain’s economic interest, the relationship is good?

Britain, as I said it before, is only interested in its socio-economic growth. Britain will always have a good relationship with any country which can contribute to this, including Turkiye.

As my last question I would like to know how you describe your identity, if asked?

When people question me if I am from Central Asia, I respond with an answer ‘yes’. I also say that I am from Cyprus.

Cyprus is my homeland; Turkiye is my natural homeland and Britain is my legal homeland. Cypriots have many identities. I have a Central Asian identity, Turkish identity, Cypriot identity, and British identity.

Firstly, I am a human being and a Turk, and of course I see the entire human race as my family, and this is my philosophy on which I base all of my work and poetry.

*Osman Türkay: 16 February 1927 – 24 January 2001

The interview was conducted in London on 12 November 1999.

This article was written by T-VINE columnist Semra Eren-Nijhar. Semra is an author, sociologist, documentary film maker & policy consultant on diversity, migration, Turkish people living in Europe and the Executive Director of SUNCUT.