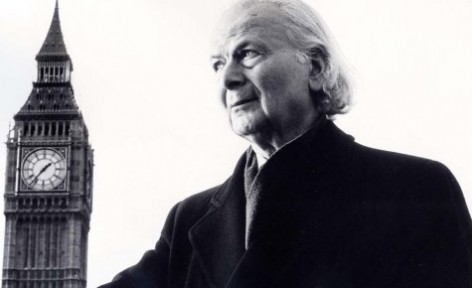

Abdullah Nihat Yılmaz is a writer and columnist. He was born in Fatsa, Turkey, in 1941 and has been living in Britain since 1981. We met recently to discuss the subject of migration literature and the notion of ‘gurbet’, which is loosely translated as ‘a place far from home’.

Abdullah Ağabey*, over the years we have had many conversations on many topics and subjects including migration. Today I would like to talk especially about migration literature with you. Do you think we can talk about migration literature in general terms and what would you like to say about it?

If we see migration as an adventure of a person, then we can talk about migration within that adventure. Perhaps in the primitive world this was not very significant, but when the workforce started to become important the property of humans became less important.

Therefore I think we can talk about migration literature. The dynamics of the migration literature is an adventure for the human being. Struggle and getting organised has something to do with coming together, but of course this is only one angle. The other angle would be the stories where love exists between two people and which reflects in a creative context and brings the adventure and love together. And if this takes place in an area where people cling to each other to survive, then why shall we not call it migration literature.

Talking about migration literature, would you agree that Turkish migrant literature exists in London?

When we talk about Turkish migrant literature we have to talk firstly about Paris, and about the books which have been written by the Turkish authors in Paris especially in the past. It is important to note that Paris cannot be compared to London.

Right now, I think we can talk about the Turkish migrant literature in London. There are some people of Turkish background in London who began writing about the subjects which were concerned with all manner of issues that faced them during the process of migration from one country to another. I am sure there will be more books published on those issues in the near future. Wherever there is a human being there is general struggle to survive and throughout human civilisation that has been converted into writing and literature.

The Crimean writer Cengiz Dağcı lived for many years in England and has produced his work away from his country of origin. He owns a place in world literature. Do you think we can say that his work is also part of Turkish migrant literature?

He has written in general about the migration of Turks and the history of central Asia. He has a lot to teach us. In his books he talks about the oppressive countries and about the people who were forced to migrate and who were exiled from those countries.

Within the notion of love he has written about the resistance movement. His writing has a special charm and he has written about real life. His pen was enthusiastic and had a good command of Turkish; he used the language very well.

So, can we classify him as an integral part of the Turkish migrant literature? I think we can also mention Osman Türkay here. Interestingly, I have always observed that once a prominent author passes away, they are not remembered by the country that they had migrated to, but rather their country of origin thus the significance of the influence of migration upon their work is forgotten.

All the positive influence is credited to the country from where these authors came from, but not to the country where they were living, producing and working.

That’s right, I think that gets forgotten. Being away from the country of origin and being in migration influences a writer’s life and is also reflected in their work. If we talk about Turkish literature in London then we can consider Osman Türkay as much as Cengiz Dağcı within it.

When Osman Türkay came to London, the number of Turkish people in London was not as many as it is now. But he always produced first in his mother tongue and later he wrote also in the English language, which he learned and therefore had a good command of it.

Unfortunately there was a time when some people within the Turkish community looked down on him and tried to minimise the important work he was doing. From the book you gave me a couple of years back, I read a lot by him and saw that he had written immensely on the subject of art and culture.

He has written a lot about the Turks living in London and Britain, so we cannot separate him from the general Turkish communities in London or in the UK.

That means we can talk about the Turkish migrant literature in London?!

Of course all these writers mentioned above are playing a very important part of the Turkish migrant literature in London. For the past 300 years, Turks have been coming and going from Europe. There have always been publications of newspapers by Turks in Europe and in Britain, some of which have not survived. Even those newspapers we have to consider as steps within Turkish migrant literature in London.

In general, I can say that Turkish authors in the past who have produced in Europe have had great influence on the Turkish people living in Europe and in the UK.

Can you explain briefly what literature is?

Literature is firstly the inner world of someone’s thoughts, which is passed on to other people through writing. The richness of these thoughts, fed through society’s activities and traumas, later have an important affect upon the individual. The beauty is within the strained thoughts of the writer. And the richness of the literature is the movement of society. Many people say if there was no Proust, then Marx would have not existed in Russia either.

Also, many people say that Atatürk was nurtured by Tefik Fikret. If there had been no Tefik Fikret, perhaps the generation of that time would have not existed as well. This is also for me the basic understanding of literature.

Everyone who came to this country for whatever reason; as a student migrant, refugee or as an entrepreneur, and settled here from Turkey and North Cyprus is part of the wider Turkish community.

The Turkish diaspora has now become more visual and there is rich research material for sociologists to work on. I think we are forming and becoming stronger within the existing wider British society. All these will have in the future a great influence on the Turkish migrant literature in London and the UK.

You mentioned before that some people looked down on Osman Türkay’s work, although he won international awards and fame. As he was actively involved in the independence movement of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus in those days, automatically he was classified as a person more on the right of political ideology than on the left. And of course it is important to note here that he was the first person who translated Neruda, Mayakovski and TS Eliot into Turkish. And in the 1950s, he was not only working in, but was part of Turkey’s mainstream literature circle.

Do you think especially in the past in Turkey, the majority of the poets or authors who made a name were more individually organised and were part of the movements of the political Left?

The ‘world of ideologies’ is a dangerous place. Even when people hear the word ideology they think it as negative. Let’s say ideologies are theories of systematic thinking. Then of course we cannot say it is not good literature if it does not fit into the theories of the systematic thinking of some people.

Osman Türkay as a Turkish Cypriot embraced Turkish literature and actually observed Turkish literature from a different country. His observation cannot be ignored. I do not take any notice of this ignorance.

In general to be able to talk and understand about Osman Türkay’s work, you have to be able to have great knowledge of world literature. In general, to analyse a society, we have to analyse their literature in order to understand it. In Osman Türkay’s case, for example, we have to analyse and understand his work in order to understand the society and literature not only in North Cyprus, but also the literature of Turkey and Britain. I mention UK as he prolifically produced and became part of British society and part of its literary circle too. You might not like him, but you cannot ignore his existence, his achievement and his work. Not liking is different to ignoring someone’s existence.

Does that mean a society’s progress on any aspect is mirrored within its literature?

That’s right. If there is any development in a society, it is reflected in its literature. Writing or verbal, literature in general captures the form of existence of human beings.

Personally I might not like literature more on the right ideology but that does not mean it is not literature. Tolstoy, like Tefik Fikret, was not a socialist, but both influenced the thought patterns of two of the world’s greatest revolutionaries.

As we are talking about migration literature, do you think we should now move away from ‘gurbet’ literature?

‘Gurbet’ means in fact trying to earn a living somewhere else or if someone dies in a war and his grave is left there, too. Or if someone falls in love and starts looking for his lover in far away places, like in the Leyla & Mecnun* story.

While I was visiting the East of Turkey years ago, they told me that when the winter snow falls and the roads are blocked for at least three months of the year, during this period people gather in one room and tell each other the story of Leyla and Mecnun over and over again. Here, the notion of ‘gurbet’ keeps repeating in this story all over again.

Köroğlu* is also told over many months in the East without any exception. I do not know how much ‘gurbet’ exists in world literature, but we can conclude that ‘gurbet’ has a special place in Turkish literature.

Being away from loved ones, being away from home, and being away from a lover creates an ‘alien place’ and I think we can name this alien place gurbet.

It is important to mention that the notion of ‘gurbet’ we talk about now is very different from the notion of ‘gurbet’ in the past.

Can you explain this in a bit more detail?

I will quote a proverb, “Your home is not where you were born but where you earn your living.” That means in the new world, where you started forming a new life far away from your country of origin, you start forming a new way of living. And in this new way of life for me ‘gurbet’ does not have the same meaning as mentioned before.

That means you do not feel yourself in ‘gurbet’?

I cannot answer this question straight away. It is a bit complicated. The meaning changed over the years while living in this country.

Personally I feel that I still want to go at any given moment to Turkey and to live there again. But anytime I go there I become restless and want to return back to London.

Now when I consider what you just said, what is your answer if asked, if you are in ‘gurbet’?

Nobody has ever put this question to me like this before; people often asked how long do I want to stay in this country?

In that case I will be the first one who asks this question. Do you feel yourself to be in ‘gurbet’?

Now you got me…Yes of course.

Can you describe the feeling of ‘gurbet’?

Firstly I am living away from my place of childhood. Secondly I am away from the place where I started to understand and comprehend the world. There was a child, a person who slowly started to understand the world he was surrounded by and started becoming part of it. Now I am away from that person and from that time.

The author Naguib Mahfou said, “Our homeland is our childhood.”

It is very true. Being away from my childhood, away from that person, away from my memories, away from my surroundings; all that gives me the feeling of ‘gurbet’, which I also mentioned before is very complicated. They involve complex feelings too.

My children were born here; people who were born and brought up here in the UK, for them the notion of ‘gurbet’ does not exist. Especially the third or fourth generation of the Turkish community not only in the UK, but also in Europe are not in ‘gurbet’.

I also concentrated my entire life to the political situation in Turkey, my struggle on that subject continued here in Britain. I was involved intellectually in Turkey and in the UK. But I can say that the intellectual environment forms over the years more where you have lived. Intellectual productivity is very important. Therefore mine is more here now than in Turkey. Naturally there is a gap between the intellectual world there and here. The gap widens according to your productivity, my intellectual productivity over the years was here in England more so than in Turkey.

That means we have to overcome the feeling of ‘gurbet’?

Someone who wants to function as a whole in society he/she lives in must be productive in order to survive the feeling of the ‘alien place’ or ‘gurbet.’ As I mentioned before one must be involved in the wider society as a whole by overcoming the feeling of ‘not belonging anywhere’ positively.

Thank you for your time for this interview.

Semra Eren-Nijhar is an author, sociologist, documentary film maker & policy consultant on diversity, migration, Turkish people living in Europe and the Executive Director of SUNCUT.

1*Ağabey, elder brother. A word respectfully used for older brother/man

2* Layla and Majnun is a love story between Qais ibn Al-Mulawah and Layla that took place in the 7th century Arabia. The poet Nizami Ganjavi also wrote a popular poem praising their love story in the 12th century who also wrote “Khosrow and Shirin“. It is the third of his five long narrative poems, Panj Ganj (The Five Treasures). Lord Byron called it “the Romeo and Juliet of the East.”

3* Köroğlu is a semi-mystical hero and bard among the Turkic peoples which thought lived in XVI. century. The name of “Köroğlu” means “the son of the blind” in Turkic languages. He is known with his epic poems during the Jelali revolts as a rebel whose father blinded by the landowner of Bolu, Bolu Beyi.