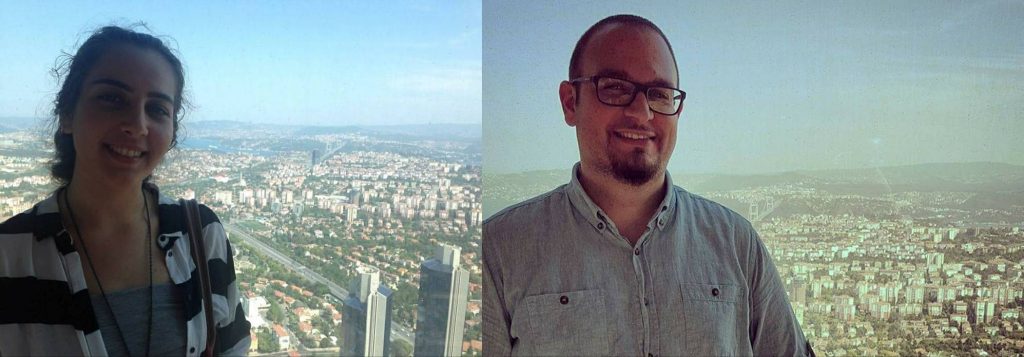

Halla Barakat was many things to many people. Many of you might recognise her as a pretty face that has been appearing in your social media news feeds in recent days, but maybe you haven’t stopped to read what all the fuss is about.

For those of you who have, you would know that Halla Barakat was a 23-year-old Syrian-American journalist who was found brutally murdered alongside her mother in their home in Istanbul last week. But for those who knew Halla, she was so much more.

Both Halla and her mother Orouba, 60, were outspoken critics of Bashar al Assad’s regime in Syria. Orouba left her native Syria in the 1980s to escape from the oppressive regime, which was then run by Bashar al Assad’s late father Hafiz. She pursued her higher education in London before moving to the US, where Halla was born.

A Syrian nationalist to the core, Orouba refused to take up British and American citizenship even when it was offered to her as she didn’t want to compromise her identity as a Syrian. Yet at the same time she didn’t want her daughter growing up with the difficulties of living forever as an exile, so she made sure that Halla was born an American. Orouba dedicated her entire life to activism, and as a journalist she even interviewed Turkey’s late former Prime Minister Turgut Özal.

Mother and daughter moved to Turkey around four years ago, leaving behind the United Arab Emirates where they had been living for fourteen years prior. Halla, eager to follow in her mother’s footsteps, enrolled as a political science student at Istanbul Şehir University, and had just graduated this summer.

Being a Syrian citizen only, her mother couldn’t legally work in Turkey, so Halla got a job as a journalist and became the sole breadwinner for the two of them. That was when I was blessed to meet them, some two-and-a-half years ago.

“From the very first day that I met her, I knew that I was dealing with a truly exceptional human being”

As Halla’s mentor, I immediately noticed her natural gift for journalism, having taken after her mother. It wasn’t long before the student became the teacher, as her skills very quickly began to surpass my own.

From the very first day that I met her, I knew that I was dealing with a truly exceptional human being. Staring into her big, beautiful blue-green eyes was like seeing Mother Earth in all its glory, and hidden behind her innocent smile and shy glances I could sense the presence of a fiery, untamable spirit that was destined to achieve great feats.

To the hundreds of men and women who prayed at their funeral and followed the procession down the streets of Istanbul chanting slogans about revolution, Halla was a flower cut down before she could blossom; a fearless warrior martyred in combat, and an inspiration to everyone who believes in the struggle for freedom. But to me, in additional to all of those things, she was a dear friend who was taken away too early.

As a Turkish Cypriot, I will always remember Halla and her mother not just as leaders of revolution, but as the only people in my seven years in Istanbul to invite me over to eat molehiya. They welcomed me into their home as one of their own and I knew Halla’s mother as “Auntie Orouba,” as did many others. Their door was open to everyone, regardless of their background, and their place was well-known to be a sanctuary of refuge for anyone in need of help or guidance, especially for Syrian refugees.

“Halla’s concern was not just for Syrians. She spoke out against oppression all over the world, from the Standing Rock protesters in North Dakota to the Rohingya in Myanmar”

Notably, Halla’s concern was not just for Syrians. She cared about all people and spoke out against oppression all over the world. From the Standing Rock protesters in North Dakota to the Rohingya in Myanmar, she stood up for justice and equality everywhere. She was also a strong supporter of the Turkish Cypriots, and would take a keen interest in what was happening on the island located just 60 kilometres from her mother’s hometown Idlib.

In our time together, we often inadvertently found many things in common between Turkish Cypriot and Syrian culture that even Turkish Cypriots and mainland Turks didn’t share. She was particularly impressed when I managed to take a photograph of a mountain peak in Syria’s coastal Latakia province from Zaferburnu in the Karpasia (Karpaz) peninsula of Cyprus. She would make a point of telling people that the Karpasia peninsula was named by Syrians who first settled in the area (Karp Asia, meaning “near Asia” in an old Syrian language). We even discovered that her mother knew relatives of my stepfather, who was also originally from Idlib.

But most of all, I think our bond was cemented by one main factor: that we were both in our own right activists for a righteous cause that we felt had been abandoned by the international community. She stood for a Syrian revolution that had first been suppressed by the Assad regime and then hijacked by terrorist groups and separatists. Everyday she would see thousands of her people being bombed out of their homes and into the sea, only to drown on their way to safety or to be met with conditions so dire that they would have preferred to die in the lands they left. All because they dared to hope for a free, fair and democratic Syria.

“Halla and Auntie Orouba were the only people in Istanbul to invite me over to eat molehiya”

Although my cause as a Turkish Cypriot campaigning for the right of international recognition was not half as dramatic as Halla’s one, we could relate to each other on a level most other people around us couldn’t. Our friendship became a source of mutual support and a bridge that united the Syrian cause and the Turkish Cypriot cause into one.

So for me, the murder of Halla Barakat is more than just a sad story in the news. It is the darkness in the room that was once illuminated with her smile, it is the silence in the air that was once filled with the sound of her laughter, it is the street I walk alone that I once walked with her. It is the tears in my eyes as I write this article. Most importantly, it is the determination in my soul to make sure her sacrifice is never forgotten.

Halla may be gone, but her spirit will live on in my own quest for justice for the Turkish Cypriots, as it will in every fight for freedom, no matter where it is in the world.

Forever in my heart Halla Barakat and Orouba Barakat, may you both rest in peace.