Securing protected status for traditional Cypriot cheese will benefit all producers on the island. However, the decision by Greek Cypriots to make a unilateral application to the European Union while deliberately excluding Turkish Cypriot producers not only turned this into a political issue, but also left a bitter taste in North Cyprus. With the EU Commission intervening, we assess whether they have done enough to win the peace or will the conflict over cheese rumble on?

Every Cypriot home is stocked with hellim – also known as halloumi. Traditionally made of either sheep or goat’s milk – or, more recently, a mixture of the two plus cheaper-to-produce cow’s milk – this centuries-old cheese gets its unique flavour and aroma from the native plants in Cyprus that the animals graze on.

Semi-hard with a salty taste and distinctive layered texture, hellim forms an intrinsic part of a Cypriot’s daily diet. It is eaten for breakfast with bread, olives, sliced cucumbers and tomatoes, or sprinkled on pasta. It can be used as a savoury filling in börek and sandwiches, grilled or barbequed as a meze dish, served fresh with chilled watermelon, or cooked as part of a big fry-up…the list is endless!

Some like this gourmet cheese fresh and moist, others mature and dry. The variations have been formulated by generations of women in villages across Cyprus who would meet to make their home-made cheese from fresh milk, salt, and yeast using traditional recipes.

Hellim is set with rennet and, unlike other cheeses, uses no acid or acid-producing bacteria in its preparation. Once made, the cheese is stored in urns, its natural juices mixing with salt-water to give it a long shelf-life way before the advent of refrigerators.

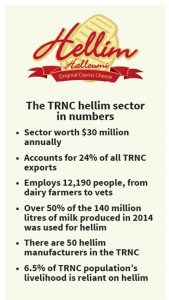

Hellim: the backbone of the TRNC economy

Today, most people prefer to buy it from their local supermarket. It’s estimated that every Cypriot consumes 8 kilos of hellim each year.

There are over 50 producers in North Cyprus alone catering to local demand, with Koop, Özlem and Akgöl being among the top brands.

There are over 50 producers in North Cyprus alone catering to local demand, with Koop, Özlem and Akgöl being among the top brands.

While the domestic market is large, demand abroad is also growing: from the Middle East to Europe and Australia, more people are feasting on traditional Cypriot cheese. Reports show UK imports of hellim/halloumi rose by 132% to 3,030 tonnes in 2012. Other big European consumers are Sweden (1,280 tonnes), Germany (870) and Austria (510).

Halloumi is South Cyprus’ second biggest export, worth over $102million annually to their economy. Due to the embargoes, the Turkish Republic of North Cyprus (TRNC) is shut out of the European market, (hence why Turkish Cypriots living in Europe often smuggle personal amounts of the cheese in their luggage after a trip to North Cyprus). However, TRNC producers sell in huge volumes to Turkey, the Middle East, and central Asia.

As the statistics demonstrate, hellim is the backbone of the TRNC economy: it is the country’s biggest export, accounting for 25% of all exports, generating $30 million each year. It is the largest private sector, employing 17% of the entire workforce. The bulk – some 11,000 people – work on dairy farms or growing animal feed, which produce over 100,000 tonnes of milk, more than half of which is used for hellim.

For the past few years, this vital part of Cypriot culture and the economy has come under threat for Turkish Cypriots.

What should have been an important opportunity to bring the two Cypriot sides together has instead become a major new political battle ground.

Greek Cypriots deliberately excluded TRNC hellim producers

PDOs (Protected Designation of Origin) are used to protect distinctive regional products such as Scotch Whisky, Italian Parmesan or French Champagne. They stop producers elsewhere from making same-name copies, which fool shoppers into paying lower prices for inferior goods while damaging sales of the genuine product.

On 17 July 2014, the Greek Cypriot government applied unilaterally to the EU Commission for a PDO to control the trade in both hellim and halloumi. While producers on both sides of the divide broadly welcomed the move to protect Cypriot cheese, those in the North were more fearful.

The application, like their earlier one in 2007, deliberately excluded TRNC producers from helping to determine the cheese’s technical properties. Nor were they named as its co-sponsors.

If the PDO progressed as the Greek Cypriots planned, it could be used to prevent producers in the North from exporting this centuries-old cheese altogether, costing the Turkish Cypriot economy millions, while generating huge unemployment.

Issue threatens to curdle relations between two Cypriot sides

The EU Commission is in a pivotal position to determine the outcome of the PDO. Intensive lobbying by the Turkish Cypriot side made it clear that by upholding a one-sided application, the EU would not only severely damage the TRNC economy, but also curdle relations between the Turkish and Greek Cypriot communities.

Such a decision would also mean the EU fell foul of its own laws, particularly Protocol 10 of the 2004 Act of Accession of Cyprus into the EU, which states that the EU is obliged to promote “the economic development” of North Cyprus.

Aware of the high stakes at play, the EU sought to reassure Ali Çıralı, President of CTCI, the TRNC’s Chamber of Industry who has been leading the charge to defend his members’ interests since the issue emerged in 2007.

On 4 April 2013, Michaela di Bucci, then Head of the EU’s Turkish Cypriot Task Force, told President Çıralı that “the Commission has clarified that Turkish Cypriot stakeholders should be involved in the framework of the prior consultation process that has to take place at national level”.

In October 2014, the EU Commission again assured President Çıralı that it was “fully aware of the great economic importance” of hellim to the TRNC and encouraged them to work with their Greek Cypriot counterparts. Yet each time CTCI has tried to have a say in the PDO, they were blocked by the internationally-recognised, but solely Greek Cypriot administered Republic of Cyprus (RoC) government.

Around the same time, there were efforts to get hellim supervised by the bi-communal UN Technical Committees, which manage joint action over Missing Persons and Heritage Sites. However, this too was blocked.

Legal flaws in the Greek Cypriot PDO application

With no alternative, in September 2014 CTCI decided to take legal action to protect Turkish Cypriot rights. Five cases were lodged at the High Court in South Cyprus challenging the RoC’s unilateral application.

The PDO’s legal flaws were communicated to the Director General of Agriculture at the EU Commission by CTCI’s Brussels lawyers NTCM O’Connor. They argued that the Hellim/Halloumi PDO could not continue in its current state as it failed to comply with both general and specific EU laws. For example, none of the PDO’s details were made available in Turkish to the producers in North Cyprus, even though this is an official language of the RoC; nor did the national procedure give TRNC producers the opportunity to make their views known or exercise their rights.

These points were also highlighted by human rights group Embargoed!. In December, their supporters bombarded Commissioner Cretu with letters urging the “European Commission [to] intervene in this matter” to ensure the application is “genuinely for the whole island”. This message was echoed by other international actors, including the British government, urged on by Westminster’s All-Party Parliamentary Group for the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.

Instead of waiting for the outcome of the court cases or enabling Turkish Cypriots to take part in the process, the Greek Cypriot authorities decided to press ahead with their unilateral plans.

Earlier this year, the temperature shot up when the South announced it was “only a matter of weeks” before the EU Commission approved the Hellim/Halloumi PDO and it was published in the EU’s Official Journal. It brought about a furious level of activity from Turkish Cypriots desperate to protect their rights.

Who will inspect hellim in the TRNC?

One of the key battlegrounds is over who will regulate the production of cheese in the North. PDOs require an internationally accredited inspection body to check the products and report into the competent authority, which ordinarily would be the Ministry of Agriculture of a Member State. However, having admitted a divided island into its midst in 2004 and only recognising the southern part, the EU openly states this authority has no effective control in the TRNC.

In January 2015, the TRNC’s then Chief UN Negotiator, Ergün Olgun, told officials in Brussels that hellim inspection should be carried out by an agency in North Cyprus. He suggested that either the TRNC’s internationally-recognised Chamber of Commerce (KTTO), which oversees the inspection of goods crossing the Green Line, or CTCI would be perfectly competent to carry out this function.

The issue was also taken up by British MEP Catherine Bearder, who wrote to EU Commissioners stressing the “significant negative impact” a Greek Cypriot-only PDO would have. In the light of this, and “the continued political position in Cyprus”, she asked the Commission to ensure that “any PDO status will be fully available to Hellim producers in both the Greek and the Turkish areas of Cyprus.”

In a written response in March, the Commission told Bearder they were happy “the application defines the geographical area as encompassing the entire island of Cyprus, and allows for the alternative or cumulative use of the terms “Halloumi”/”Hellim” by any eligible producer that fully meets the related specification.”

The Commission also stated that, “Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 requires the establishment of an appropriate control mechanism encompassing all eligible producers throughout the island. In the case of Cyprus, this will need to take into account the circumstances prevailing on the island. An effective control mechanism has to allow all eligible producers to fully benefit from registration of “Halloumi”/”Hellim” in order to help maximising all possible benefits.”

In March, the PDO application was hanging by a thread as agreement could not be reached on the technicalities. Even if all Cypriot producers agree on the ingredients – and many Greek Cypriot producers are deeply unhappy with their own government’s specifications, which limits the amount of cow’s milk in halloumi – the Commission was seemingly unable to proceed until it clarified who would inspect production in the TRNC.

EU forced to suspend Hellim/Halloumi PDO application

As CTCI lawyers pointed out, it is not unusual for there to be multiple competent authorities and control bodies supervising Geographic Indication registrations in EU Member States. So the Hellim Issue could be solved by appointing independent inspectors in the north, answerable to the EU without coming under the direct control of the authorities in South Cyprus – a red line for Turkish Cypriots who have been battling for decades to safeguard  their political equality.

their political equality.

However, the Greek Cypriot authorities, unwilling to share power with their peers in the North, strenuously resist any efforts to undermine their long-held policy that they – and they alone – are responsible for governing the whole island.

With both sides digging in, the PDO had reached an impasse, with all eyes on Brussels on what would happen next.

Sensing trouble, in February 2015, the Commission had already asked its Legal Department to provide an opinion on how they should manage this issue. One idea was to publish the PDO, but to clarify that there will be an exemption for North Cyprus, which required an alternative inspection mechanism.

This news infuriated the Greek Cypriots and their Foreign Minister Kasoulides threatened to take the Commission to the European Court of Justice. Given the RoC’s clear failings on the handling of the PDO national consultation, it is unlikely the ECJ would deliver them a positive legal ruling.

“Hellim is a joint produce of the island. Its owner is not Greek Cypriot”

However their unwillingness to accommodate Turkish Cypriots in the process on an equal basis generated an equally strong response from the North, uniting political parties and producers.

Akgöl’s owner Sadık Gürün said, “Hellim is a joint produce of the island. Its owner is not Greek Cypriot. If the PDO went ahead [as it stands] our business would come to a standstill. The TRNC has many hellim producers. For that reason we are all working hard to avoid this becoming a one-sided PDO…We believe the EU will not allow hellim to come under the sole control of Greek Cypriots.”

Akgöl’s owner Sadık Gürün said, “Hellim is a joint produce of the island. Its owner is not Greek Cypriot. If the PDO went ahead [as it stands] our business would come to a standstill. The TRNC has many hellim producers. For that reason we are all working hard to avoid this becoming a one-sided PDO…We believe the EU will not allow hellim to come under the sole control of Greek Cypriots.”

KTTO President Fikri Toros agrees and told T-VINE: “Mindful of the prevailing political reality on the island, the control mechanism in North Cyprus must be set up in such a way that it does not become dependent on the effective control of the Greek Cypriot authorities.”

In April, KTTO and CTCI were informed by the Commission that the PDO was on hold until it can determine an effective control mechanism for North Cyprus, which can verify compliance by producers. It seemed the north’s immediate battle to preserve hellim rights had been won.

EU President Juncker negotiates hellim deal

Knowing the suspension of the PDO was a temporary measure, the newly elected TRNC President Mustafa Akıncı raised the Hellim Issue during his visit to Brussels at the end of June. Het met with the heads of three major EU institutions, including European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker and European Parliament President Martin Schulz.

In a follow-up visit to Cyprus in mid-July, Junker announced that he had agreed an acceptable formula with the two Cypriot leaders. The administration of the PDO would be managed differently in North Cyprus by an independent inspection body who would report into both the Commission and South Cyprus.

For the first time since 1994, EU markets would also be open to Turkish Cypriot producers who would be able to sell hellim via the Green Line following an amendment to the relevant Regulation.

Several concerns remain for those in North Cyprus. There was no express reference in the EU’s subsequent press statement on 28 July published on the same day about the equal rights of Turkish Cypriots over hellim – a core demand of the TRNC business groups that had previously lobbied the Commission.

Will Turkish Cypriot producers meet EU hellim criteria?

The newly appointed inspection body Bureau Veritas also has a conflict of interest, as it holds major contracts to inspect shipping in South Cyprus, giving it a natural bias towards Greek Cypriots. Embargoed! has already made strong representations to EU Commissioner Cretu on the issue, extracting a response that “the Commission will ensure that an effective and objective control mechanism for Halloumi/Hellim” is established.

Another question mark hangs over whether Turkish Cypriot producers will be ready to meet the PDO requirements when it kicks in? Unlike their peers in South Cyprus, they have not received any funding and support needed to bring them up to EU standards.

Currently hellim is mostly made of cow’s milk, which is the cheapest to produce. Yet the PDO requires at least 20% of the cheese to be of sheep or goat’s milk – rising to 51% in ten years’ time.

Historically, hellim used to be made entirely from goat or sheep’s milk. Today, it only contains about 3%. North Cyprus has the potential to reach 20%, but it will take time.

Then there are the multiple EU health and safety rules governing food production that need to be complied with.

If Juncker’s deal does not allow an exception for TRNC producers, they may well find that for a period of time they will not be able to call their produce ‘hellim’.

Weeks after signing Juncker deal, Greek Cypriots try to backtrack

There are more worrying developments too. President Anastasiades is demanding changes to the Hellim trade deal he made with the TRNC, just weeks after signing.

The agreement, brokered by the President of the EU Commission, and hastily announced on 16th July after a successful lunch with the two Cypriot Presidents, was taken as further proof of the new atmosphere of optimism surrounding the perennial Cyprus Peace Talks.

But according to news reports in South Cyprus’ leading daily Phileleftheros, the RoC’s office of permanent representation in Brussels has submitted a request for “substantial amendments” to the agreement, after receiving instructions from President Anastasiades.

Responding to widespread criticism of the deal, the Greek Cypriot leader now wants four key amendments. It includes dispensing with the separate quality-inspection arrangements for North Cyprus as the South claims this would “infringe the RoC’s sovereignty”.

They also want all hellim from the TRNC – including products destined for Turkey and other non-EU markets – to come through the Green Line instead of being sold direct.

The demands have been met with dismay in many quarters, including Turkish Cypriot industry body CTCI. Its Secretary General Doğa Dönmezer said “the situation is of grave concern”, which they are “monitoring closely.”

One political commentator in the Greek Cypriot Cyprus Mail cheekily observed, “You have to wonder whose advice Nik [sic] follows before making these decisions. What credibility would Anastasiades have when he is seeking changes to an agreement he reached two months ago in the presence of the EU chief? Will he do the same when he signs, God forbid, a settlement?”

One political commentator in the Greek Cypriot Cyprus Mail cheekily observed, “You have to wonder whose advice Nik [sic] follows before making these decisions. What credibility would Anastasiades have when he is seeking changes to an agreement he reached two months ago in the presence of the EU chief? Will he do the same when he signs, God forbid, a settlement?”

Hellim Wars, like the Cyprus Conflict, is set to continue for some time yet…