Turkish scholars fired from their jobs following a mass purge in Turkey have found an unexpected guardian angel in Germany. In a bizarre twist of fate, the Philipp Schwartz Initiative, launched last year and inspired by a German Jewish academic saved by Turks, is helping refugee researchers fleeing persecution in their home countries to find new employment.

The scheme, run by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation in Bonn, is named after Philipp Schwartz, an Austro-Hungarian pathologist who worked for the Goethe University in Frankfurt for 14 years until he was fired by the Nazis in 1933 for being Jewish. Schwartz escaped to Switzerland and founded the Emergency Association of German Scientists Abroad, which supported academics forced into exile.

Historically, the Turks have offered Jews a safe haven many times during the last millennium. During the Middle Ages for example, when tens of thousands of them were expelled from Europe, they were welcomed by the Ottomans. At the end of the 19th century, the Ottomans again absorbed thousands of Jews fleeing pogroms in Tsarist Russia.

In the 1930s, having returned and re-integrated into Germany, Jews faced a new threat: the Nazis. After becoming Chancellor of Germany in January 1933, Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party used violence and intimidation to consolidate their power base. One of their primary policies was to persecute Jews. They instigated a boycott of Jewish businesses, and passed a law preventing Jews from being employed by the government.

It was during this time that Philipp Schwartz found himself out of work. He contacted the Turkish Republic, then just a decade old, to ask for help. Its President, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk duly obliged, paving the way for some 150 German Jewish professors to be employed by Turkish universities. Schwartz himself became appointed the director of the Department of Pathology at the University of Istanbul.

Seven decades on, a German initiative that bears Schwartz’s name is returning the favour.

Thousands of Turkish academics have lost their jobs following the failed coup of July 2016. Some were accused of being a member of FETÖ, a quasi religious-political network led by Islamic cleric Fethullah Gülen, once a close ally of the AKP government but now considered a terrorist responsible for last summer’s coup attempt. Others were charged with making propaganda for the PKK, a Kurdish terrorist organisation.

In a radio interview on 11 Feb., Prof. Yalçın Karatepe, formerly a dean at the Faculty of Political Sciences at Ankara University, said the current purge against academics was on a par with previous military coups in Turkey, which severely clamped down on intellectuals.

Arrested academic likens Turkey to “darkness of medieval ages”

Most educators, like historian Candan Badem and Sultan Aktaş, a high school teacher, refute the charges, claiming the AKP government is waging a witch hunt against them for openly challenging its increasingly authoritarian policies.

Badem’s case has been re-told in various media, including the Times Higher Education online. The self-proclaimed Marxist atheist academic was arrested and lost his job at Tunceli University last August when he was accused of supporting FETÖ. A book by Fethullah Gülen found in Badem’s office was used as evidence against him, in spite of the fact the scholar regularly criticised Gülen in his comments and lectures. Yet even with such flimsy evidence, the onus is on him to prove his innocence.

Badem told the New York Times: “It was like a bad joke. What kind of reason can this be, for an academic to have a book? It is like the darkness of the medieval ages.”

Turkish academics paying price for being a “pit of treachery”

Another reason why Badem may have been targeted by the Turkish authorities was for signing a one-sided petition in January 2016 that criticised the Turkish government for its “brutal” handling of the explosion of terror in Southeast Turkey. The petition, which received international backing from renowned academics such as Noam Chomsky, David Harvey and Slavoj Žižek, had failed to condemn the PKK, even though it had resumed its war against the Turkish state. The terror group took its battle into urban areas such as Diyarbakır, and so fierce was the fighting between PKK militants and the Turkish military that it left parts of the region looking more like war-torn Syria.

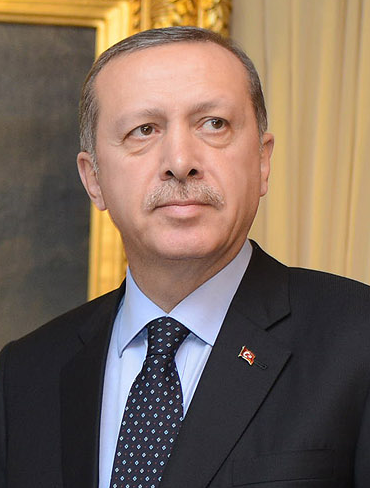

Following the release of the petition, which received global media coverage, an angry President Erdoğan told Turks that the academics would pay a price for their “pit of treachery.”

In a blistering attack during a meeting at his Presidential Palace last January, Erdoğan said, “They spit out their hatred of our nation’s values and history on every occasion and the petition has made this clearer.”

In a direct threat to the academics, he added: “So you think you will try to disrupt the unity of this nation, and continue to have a comfortable life with the help of the salary that you receive from the state and pay no price? Those days are over.”

Over the past 12 months, most of the 1,200 Turkish academics who pledged their support for the ‘Academics for Peace initiative’ have faced action from their universities: either they were suspended pending an investigation or dismissed from their posts, with some also detained. Those tainted by the purge are unable to gain employment elsewhere, forcing them abroad just to survive.

Sadly, there seems no end to either the purge, which by 31 Jan. 2017 had resulted in over 95,000 public servants sacked, among them judges, soldiers, police officers, and teachers, or the brain drain. In the first week of 2017, another 631 Turkish researchers and professors were fired. Those free to flee are doing so, with many seeking refuge in Europe.

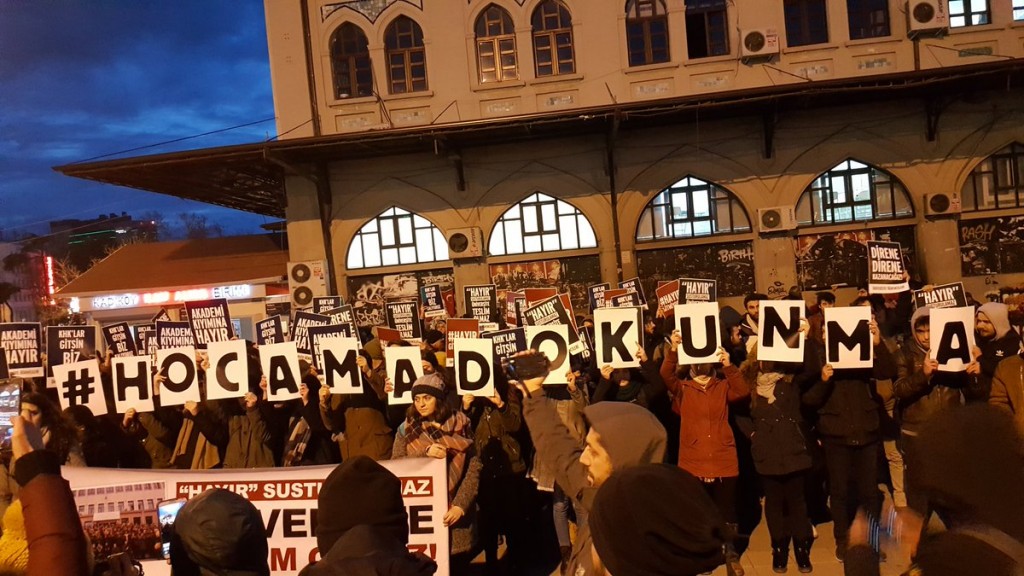

Police responded brutally to protesting academicshttps://t.co/e1VYqmbCji pic.twitter.com/0hWksXGx0D

— soL internationaL (@soLIntern) February 11, 2017

Majority of applicants to Philipp Schwartz Initiative are now Turks

When the Philipp Schwartz Initiative launched last March, the largest number of applications came from Syrian refugee academics. In the latest round, the majority of applicants – 46% – were from Turks. It is thought between 100 and 150 of those who signed the Academics for Peace petition, such as Halil Ibrahim Yenigün, a professor who was fired from Istanbul’s Commerce University, are now in Germany.

According to a statement on its website, the Philipp Schwartz Initiative “supports researchers who seek refuge in Germany because they are threatened by war or persecution in their own countries.” It offers funding to academic institutions who take on refugee academics and a fellowship grant (a monthly salary) to the “threatened researcher” that lasts for up to two years.

To date, 69 researchers from Syria, Turkey, Iraq, Burundi, Yemen, Libya, Pakistan, Sudan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan gained employment at German institutions as a result of the scheme. The new round of the programme will bring the total number of fellowship recipients to approximately one hundred from August 2017.

It is a tragic irony that a country which once opened its arms to those fleeing persecution is now responsible for driving its own intellectuals abroad, straight into the warm embrace of Germans.

Main photo above of a recent protest in Turkey against the ongoing purge against academics, using the popular slogan #HOCAMADOKUNMA [‘Don’t touch my teacher’]