Two weeks ago, an angry mob attacked an art exhibition at Istanbul’s Abdülmecid Efendi Pavilion. The building used to belong to the last Ottoman Caliph Abdülmecid.

The exhibition, called Doors Open to Those Who Knock, showcased artwork owned by Turkish businessperson Ömer Koç. It opened to public at the Pavilion during the 15th Istanbul Biennial, which is organised by the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts and sponsored by Koç Holding.

Ron Mueck’s nude sculpture titled The Man Beneath the Sweater, seated within an antique tiled fireplace in the gallery, was the attackers’ primary target, according to Turkish news website T24.

A group of five people shouted, “Is this secularism?”, “The country has reached this low because of [people like] you”, and “You can’t show this here!” They attempted to damage the artwork, assaulting a security guard in the process, who was pushed to the floor as he tried to stop them vandalising the artwork.

Other security guards arrived to help prevent the protestors from reaching the sculpture. They were eventually escorted away from the gallery space when it was clear they would continue to attack the exhibition.

Officials at the exhibition believe the attackers mistook the fireplace for a religious setting: either a minbar, or pulpit, where an imam stands to deliver sermons, or perhaps a mihrab – a semi-circular niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the qibla (direction of the Kaaba in Mecca), which guides Muslims in which direction they should face when praying.

Following the incident, Koç Holding released a statement making it clear the Abdülmecid Efendi Pavilion has never been used as a sanctuary or a holy site. Moreover, the fireplace feature happens to face southwest, while the qibla always faces southeast.

It’s likely that the protestors, one of them Mahmut Alan a former activist for a far-right party, were fuelled by the neo-Ottoman fantasies constantly churned out by Turkey’s conservative newspapers and various social media users, including. Nilhan Osmanoğlu, granddaughter of the Ottoman Sultan Abdülhamid II.

On the day of the attack, Osmanoğlu tweeted: “The exhibition displayed by the Koç family at the mansion of the last caliph, Abdülmecid, should be removed! This disguised ‘exhibition’ in Kuzguncuk is a disgrace”.

Son Halife Abdülmecid’in evinde Koç tarafından açılan sergi durdurulmalı! Kuzguncuk’ta bulunan sergide sanat adı altında “rezalet”!!! pic.twitter.com/0nqTfCNg1e

— Nilhan Osmanoğlu (@NilhanOsmanoglu) October 21, 2017

Newspapers Yeni Söz and Takvim also pointed to the exhibition and Biennial as legitimate targets and reported the incident as “the disgrace exhibited in the historic mansion caused a scene”. However, these comments cultivate perceptions that are far removed from reality.

As a spectacular example of late Ottoman architecture, the Abdülmecid Efendi Pavilion was initially a hunting lodge built by Isma’il Pasha, before Ottoman Sultan Abdülhamid II bought it for his nephew Abdülmecid.

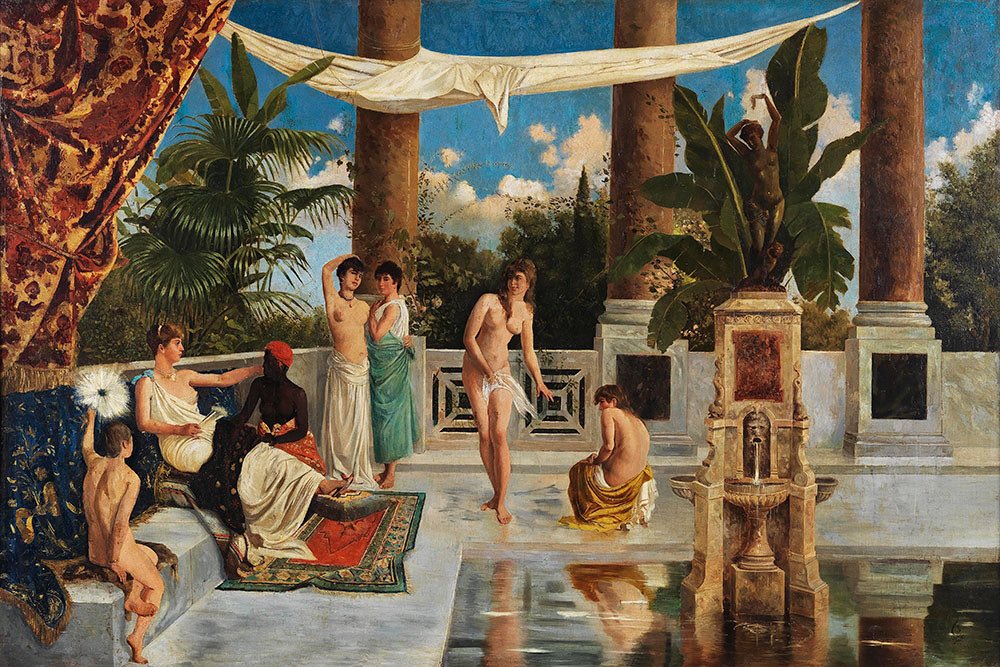

Abdülmecid was not only the last caliph, but also one of the great artists of the late Ottoman period. He usually used the Pavilion for his art work and meetings. So the building, which was portrayed as a ‘holy’ mansion by Ottoman-obsessed conservatives and their media outlets, was, ironically, originally a house of art. Moreover the artist-caliph, whom they see as their ancestor but about whom they know precious little, also liked to paint semi-naked women.

One of the last caliph’s paintings, known as Women in the Courtyard (main picture above), depicting semi-nude women was sold at auction in 2013 for 1.6 million TL ($800,000 at the time). Bora Keskiner of Alif Art, the Istanbul auction house which handled the sale, told Reuters: “There have been questions about whether the conservative government and new elite would be comfortable with a painting by the caliph that features nudes. The work is an important signifier of how the late Ottoman Turkish elite and royal family were extremely close to European art circles and they themselves practiced European art.”

Keskiner’s words from three years ago are just as apt for today’s political and social climate. The Justice and Development Party (AKP) Government and support base constantly use Ottoman discourses to bolster their ideology, seemingly indifferent to the need for historical accuracy. Instead, their sanitised history of the Ottomans underpins their vision of New Turkey: an infallible state whose strength comes from its moral values.

The Pavilion incident highlights the need to counter intolerance. As Koç Holding stated, one of the most important aspects of community development is freedom of opinion and one of its most effective channels is Arts and Culture.

Just like the Abdülmecid Efendi Pavilion, historical buildings around the world host exhibitions to bring the ‘questioning’ power of art to the community. It is this real strength which is lacking in these Ottoman-obsessed hallucinations, which possess little more than surface knowledge about the heritage they claim to admire so much.