According to Taner Derviş, most of Maraş – the ghost town claimed by Greek Cypriots as inalienably “theirs” – still legally belongs to Evkaf, a Muslim charity dating back to the Ottoman conquest of 1571. The former director of Evkaf says these rights have been re-confirmed in every Cyprus Constitution since then.

Under Turkish Cypriot control and uninhabited since the 1974 War, Maraş, measuring 2.3 square miles, is part of Famagusta. Greek Cypriots have convinced the world this coastal town is “theirs”. The UN and European Parliament have passed resolutions demanding it is returned to its “lawful” inhabitants, while South Cyprus leaders regularly propose Greek Cypriots be allowed back to “their” properties as a confidence-building preliminary to the Cyprus talks.

North Cyprus has long claimed Maraş is Turkish-owned, but failed to present any evidence. All debate was in Turkish, meaning those from other countries could not access the facts. That is now changing.

In a talk entitled ‘Property and compensation rights of the Evkaf Foundation and the Issue of Maraş’, given at Westminster earlier this year, Derviş showed that this once fashionable resort of British and Hollywood stars is still, in fact, legally Turkish-owned. Evkaf (short for Kıbrıs Vakıflar İdaresi – or the Islamic Trust of Cyprus) still holds deeds to most of it – some 500,000 dönums.

Derviş’s starting point is the edict passed by the Sultan soon after the conquest that established the Evkaf. It states that any property bequeathed to Evkaf for the benefit of Cyprus’ Muslim community is ‘irrevocable, perpetual and inalienable’ and that should the trust be deprived of it, it must be compensated.

He also presented evidence that Evkaf land was never sold by Turkish Cypriots to the British. The evidence gleaned from title deeds “proves” that under British rule Turkish-owned property was “illegally transferred”.

Evkaf rights embedded in Cyprus Law

Britain prised the island from the weakened Ottomans in 1878. During World War I, Cyprus’ status changed from a British Protectorate to being under British occupation, and then a Crown colony in 1922. Article 60 of the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne stated that trusts created under the Ottomans would be maintained under British rule.

The same principle is also included in the Republic of Cyprus’ Constitution of 1960. Article 110 states that “no legislative, executive or other act whatsoever shall contravene or override or interfere with such Laws or Principles of Vakfs.” And Annexe E of the 1960 Treaty of the Establishment of the Republic of Cyprus states: “all legal liabilities and obligations incurred by the government of the Colony of Cyprus” are passed on to the new Cypriot Government.

Interestingly, Appendix U of the same Treaty stated that the British Government was, “making available the sum of £1,500,000 by way of a grant to the Turkish community in Cyprus to be used for education, the development of Vakf property and cultural and other like purposes.”

Derviş, who spent 32 years working at Evkaf, believes this grant by the British to Turkish Cypriots is the root of the popular myth about the so-called sale of Evkaf land by Denktaş and Küçük for £1.5 million. Simply put, no sale took place.

He also cites landmark cases that were won using these laws. Evkaf ownership rights were upheld in the Arabahmet Aqueduct case in Nicosia in 1914, and the Tersefan Farmland action in Larnaca in 1958.

British illegally transferred Maraş to Greek Cypriots

Derviş insists that Evkaf is the “greatest landowner in Cyprus”. Over the centuries, many Cypriot Muslims left land to Evkaf, hence its accumulation of huge wealth. However, the Ottomans granted benefits to others too: Greek Cypriots had lived as Orthodox serfs under Catholic Venetian rule, but the Turks gave them numerous rights, including religious independence and ownership of land.

Derviş insists that Evkaf is the “greatest landowner in Cyprus”. Over the centuries, many Cypriot Muslims left land to Evkaf, hence its accumulation of huge wealth. However, the Ottomans granted benefits to others too: Greek Cypriots had lived as Orthodox serfs under Catholic Venetian rule, but the Turks gave them numerous rights, including religious independence and ownership of land.

In 1924, two years after Cyprus formally became British, a land census showed that one third was owned by the Sultan, one third by Muslims, and one third by non-Muslims. Land listed under the Sultan and Muslim owners also included land held in trust by Evkaf.

Following the collapse of Ottoman rule, much Evkaf land was usurped by Greek Cypriots – primarily individuals, but also businesses, schools and the Greek Orthodox Church, who all helped themselves to Turkish-owned land. Derviş presented numerous title deeds from the past century where Evkaf land was unlawfully transacted, with Greek Cypriot names on the deeds authorised by British officials.

Derviş argued that Britain was complicit in these unlawful transfers. Laws were ignored, court decisions in favour of Evkaf were not upheld, key documents were ‘lost’ and Evkaf resources were mismanaged.

The trust’s research indicates some 77% of Maraş was illegally occupied by Greek Cypriots in this way, with similar unlawful occupation of Evkaf land across south Cyprus.

Taner Erginel, a former Chief Justice of the TRNC, concurs. He describes his own research into the validity of the title deeds in Maraş: “Under Ottoman and early British rule, Maraş belonged to Evkaf. In 1907 the British Colonial Administration passed a general prescription law (Law 12/1907) allowing people to own properties they possessed without dispute for 10 years; similar English Law specifies 12 years. Under this law Maraş titles were transferred to Greek inhabitants.”

“However in 1907, there was another law in force in Cyprus: Ahkamul Evkaf – the Law of Religious Foundations. According to Ahkamul Evkaf, no Evkaf property could be owned by way of prescription. Evkaf property title is owned in perpetuity. Since Ahkamul Evkaf is a specific law for Evkaf properties it has priority and should have been applied instead of any other law. Applying the general law of 12/1907 and not the specific law was wrong and against legal principles. So Greek Cypriot title deeds relating to Maraş are defective.”

Why is Evkaf only now asserting its property rights?

The evidence sheds a whole new light on key property judgments in Cyprus, including the Arestis test case. In 2005, Ms. Xenides-Arestis won a claim of compensation against Turkey at the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) without providing any deeds to the land she claimed her family owns in Maraş.

Evkaf was not a party to the Arestis case. The ECHR ruled that a local body be created to find legal remedies for Arestis and 1,400 other property cases involving Greek Cypriot refugees. Once the TRNC’s internationally-accepted Immovable Property Commission (IPC) was established, Evkaf also applied.

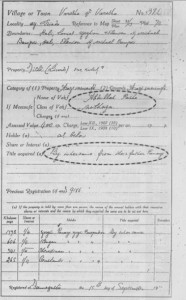

The Trust’s lawyer has since presented evidence from the Famagusta Land Registry that showed the Arestis land was actually owned by the Abdullahpasha Vakfı and had been unlawfully transferred to a Greek Cypriot. Derviş presented copies of these deeds in his talk too. Dated September 1913, October 1949 and February 1974, each highlighted the unlawful transfer of Evkaf land and also failed to record either the amount or the purpose of the exchange. So in addition to being constitutionally “estopped”, the contracts were also illegal as there was no consideration (payment).

The Trust’s lawyer has since presented evidence from the Famagusta Land Registry that showed the Arestis land was actually owned by the Abdullahpasha Vakfı and had been unlawfully transferred to a Greek Cypriot. Derviş presented copies of these deeds in his talk too. Dated September 1913, October 1949 and February 1974, each highlighted the unlawful transfer of Evkaf land and also failed to record either the amount or the purpose of the exchange. So in addition to being constitutionally “estopped”, the contracts were also illegal as there was no consideration (payment).

Unsurprisingly, Greek Cypriot refugees objected to Evkaf’s application to join their cases. However, the TRNC’s Constitutional Court judged that it was important to determine the lawful owners of property before compensation, restitution or exchange could be agreed. Given Evkaf’s comprehensive evidence, the Court ruled that the Trust be admitted as a party to all Maraş claims before the IPC.

Asked why evidence was only just emerging, Derviş said that it was important to provide unequivocal proof of ownership, which had taken decades to compile. Some deeds were in the Ottoman archives, others were split between the Turkish and Greek Cypriot Land Registries: “We are at the tip of the iceberg with the paper copies, as it is taking time to mine the considerable British, Ottoman and Cypriot property archives.”

He added that the South was not interested in helping to prove Evkaf ownership and until recently, there was no digital technology to simplify the research. However a partial map of land ownership in Cyprus, all backed by deeds and other legal proof, was now emerging.

International treaties and Cyprus laws demonstrate clearly that both the British and Cypriot Governments were legally committed to protecting Evkaf-owned land. The politicians can debate which community will control which area, but they cannot ignore past ‘mistakes’ or override the law when it comes to determining the rightful owners of property. In Maraş, the evidence supporting Turkish Cypriots seems to be overwhelming.