Galip Ahmet is one of the first Turkish Cypriots to have come and settled in Britain in the early 1950s. Born in Cyprus on 18 April 1929, Galip Bey recently turned 90.

I interviewed him earlier this summer about his experiences before and after his move, as part of my work on ‘Turkish heritage in the UK’. It’s a subject I have researched for many years, as I believe collecting these vital memories of our past will impact on our collective existence in the present, whoever and wherever we are.

Galip Bey, what did you do in Cyprus before you came to Britain?

In the late 1940s in Cyprus, I was working for newspapers like Ateş, Hürsöz, İstiklal Gazetesi and Halkın Sesi, and many other papers as an ad man.

I obtained advertisements from Greek newspapers, translated them and got them published in Turkish papers in Cyprus. I kept 10% for myself and the rest I would give to the papers.

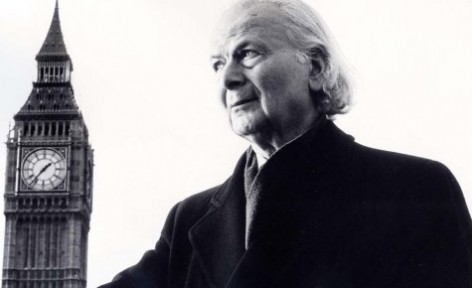

In those days, the maximum print run for any newspaper was only 1000 copies. It was also in those days that I met my closest friend Osman Türkay, who was a columnist for one of the newspapers.

I started working at a very young age, as I was not from a well-off family. I was born in a village and like many villagers in those days, we were all poor and that is how we grew up, in poverty. We did not have much money. We had to work hard to earn our living.

I have seen the same poverty in Anatolia too. The poor are poor everywhere and it affects your life. Anyone who knows what poverty is will know what I am talking about. The rich are always exploiting those who are not well off; the poor face the same treatment not only in Cyprus, but everywhere around the world.

Did you have any negative experiences while growing up and working in Cyprus?

Yes. For six years I was working for a family, day and night. I was very respectful and duty-conscious. I was not only working for this family, but also for their extended families. I went shopping for three families and looked after their children.

The man I was working for was a dentist. I was doing a lot for him, like going to the pharmacy; if needed, I would even measure tooth implants for his clients. I was like a runner boy for everything.

When I said that I was leaving as I had got a job at the newspaper, he did not appreciate my work over all the years I did for him. He gave me just £12 as a pay-off for my services, which was like giving a derisory amount of money you give to a beggar.

Did your friends have similar experiences?

In Cyprus there were a few very rich families. These families never wanted to see a person from a village; a villager never improves his/her life standard. It was like an old system, like a feudal landlord owning everything. Many people like myself from a poor family, had to go through this.

Therefore from an early age I knew the only escape from this situation was to get a good education, build up my knowledge and to improve myself in all aspects of my life.

I self-taught myself everything by reading, and having very educated people in my circle; I talked to professionals and improved my cultural knowledge in all aspect of life.

I remember very clearly at the beginning of the 1950s, a lot of Turkish Cypriots who needed work and wanted to improve their life standard went off to the Suez Canal in Egypt. In those days the Suez Canal needed labour. Turkish Cypriots took the opportunity and went.

Later, a majority of them came to settle here in Britain after they had saved some money from the time they were working in Egypt.

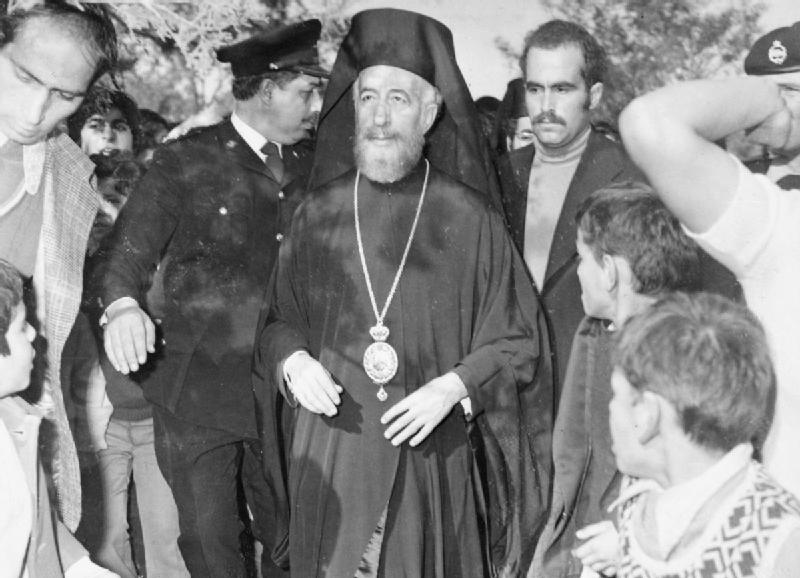

You mentioned that Archbishop Makarios was your neighbour and you knew his entire family.

Makarios’ village was very close, only a short walking distance from my village. In those days everyone spoke Greek, as we were all mixed around the island. I spoke the Greek language very well, as my family was living next to a village of Greek neighbours.

Makarios was born in the village Pano Panayia. His church was only 200m distance from where we were living. I had a different acquaintance to him than other Turkish Cypriots, as my mother was a tailor: she stitched robes and other clothes for the clergy. Between 1945-1950 Makarios was also her customer and she stitched clothes and robes for him too.

We had conversations whenever he came to our house. Not only Makarios, but also his mother and sister would often visit our house and we all had good relations with each other. I even visited him after he became the Archbishop of Cyprus and moved to Nicosia.

Tell us about the time short time you went to live in Turkey.

I went to Adana as my dayı was living there. After a short time, I was determined to go to Ankara as I wanted to see some government officials to complain about the civil servants who were sent to Cyprus and were doing nothing on the Cyprus issue. Literally nothing; except enjoying their lives, drinking whisky and having fun.

The Greeks already had their schools and colleges, and were continuing their lives as normal. None of the officials from Turkey who were actually supposed to come to our villages and talk to us about our needs and problems were anywhere to be seen. And I knew if we would not take this matter in our hands, nothing would change. I wrote letters concerning this issue to the then President of Turkey İsmet Paşa and later to Celal Bayar.

It looks like you had very big plans in Ankara. Did anyone help you initially?

I knew an actor from the State Theatre Company, Haşim Hekimoğlu, who had come to Cyprus to perform. I publicised their plays for free in the papers and we became good friends. He was like an older brother to me.

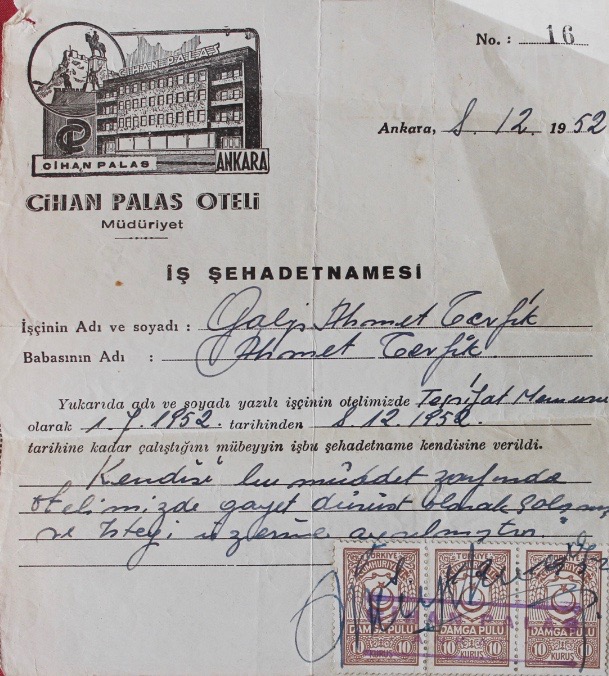

On my arrival I stayed with him and I quickly found a job at the British Embassy in Ankara and moved into a hotel whose owner I knew when he had visited Cyprus as well. During his stay in Cyprus I helped the hotelier too.

Shortly after my arrival in Ankara I moved into the hotel. The owner asked me if I would work at the reception during the evening, after my embassy job, as I was fluent in English and that he needed someone like me.

The hotel was one of the biggest and well known hotels in Ankara, and at that time where all the government officials, politicians, dignitaries and state visitors would come to stay or dine at its restaurant. It was the famous Chin Palas Hotel. People like King Paul of Greece and the Shah of Iran visited the hotel too.

Osman [Türkay] joined me in Ankara too. We were both active in Cyprus politics, and then at the heart of the capital city of the Republic of Turkey.

Were you able to have a meeting with a member of the Turkish government?

I tried everything conceivable to reach Turkish government officials in Ankara and talk to them about the situation of the Turkish Cypriots, but unfortunately without any luck whatsoever. But I never gave up. I even brought some newspaper cuttings from Cyprus as proof for government officials, in case they wanted to know what was going on.

We knew that the Greeks were secretly organising against the Turks, but nobody would believe us or do anything about it. Finally with my push sometime later I managed to see Prof. Dr. Mehmet Fuat Köprülü – Turkey’s Minister of Foreign Affairs – who was, along with Adnan Menderes, one of the founders of the Democratic Party that was formed in 1946.

So in the end you succeeded in seeing someone influential in Ankara?

I wished I had never met him [Prof. Köprülü]. It was a humiliation. He did not believe what I told him. He berated me and got very angry with me. He said I was careless and added very clearly: “We do not have, and Turkey does not have any such thing as a ‘Cyprus Problem’.

He continued to tell me off by saying, “Shall we take our country to war because of you? If you are all so unhappy in Cyprus, come and settle in Turkey. We have lot of space for all of you in Anatolia”!

He dismissed me and showed me the door. After the meeting with him, I told everything to Osman with tears rolling down my eyes, recounting as to what had happened in the meeting.

Did you give up?

No. On the contrary I passionately continued my work. Shortly after that meeting, Osman and I met with Dr. Fazıl Küçük and Dr. Niyazi Manyera who were visiting Ankara from Magusa. We held some meetings concerning the situation in Cyprus. We were doing everything in our power to change things for Cyprus.

Again Osman was doing his best as well as a journalist and writer to draw attention to the situation, which was worsening between the Greeks and Turks in Cyprus. The Turkish officials from Turkey visiting Cyprus were not listening to us though.

What happened?

I explained everything to the journalist whom I had befriended at the hotel. I think he was working for the Türk Haberler Ajansı or for Hürriyet in 1952. I asked him to take me to his senior at the paper. He kindly organised a meeting and we went to meet Sedat Simavi who was passionately following the developments in Cyprus and was sensing that the situation for the Turkish Cypriots was not looking so great.

Cyprus was undergoing a serious political struggle since 1950 and he sympathised with the Turkish Cypriot predicament.

I told everything to Simavi, including my meeting with Prof. Dr. Fuat Köprülü and how he insulted me by saying there is no ‘Cyprus Problem’ and showed me the door. Sedat Simavi published all this as a headline in Hürriyet, which came as a big blow for the Turkish government.

Then, as a result of this [article], all the other Turkish media got interested and finally we drew serious attention about the Cyprus Problem to the people of Turkey too. It really highlighted the shortcomings of Turkey’s foreign policy on Cyprus at the time.

Although Sedat Simavi and Turkey’s Foreign Minister Fuat Köprülü were friends, Simavi kept his work separate from their personal relationship. Sedat Simavi was a very important, irreplaceable and an elusive journalist.

From Ankara you then decided to travel to London?

Osman and I thought we had finished our duty in Turkey and should travel on to Britain. First we went to İzmir, and from there took a ferry to Marseille. After spending ten days in Marseille, in France, we travelled by train and then boat to Britain. We arrived in November 1953.

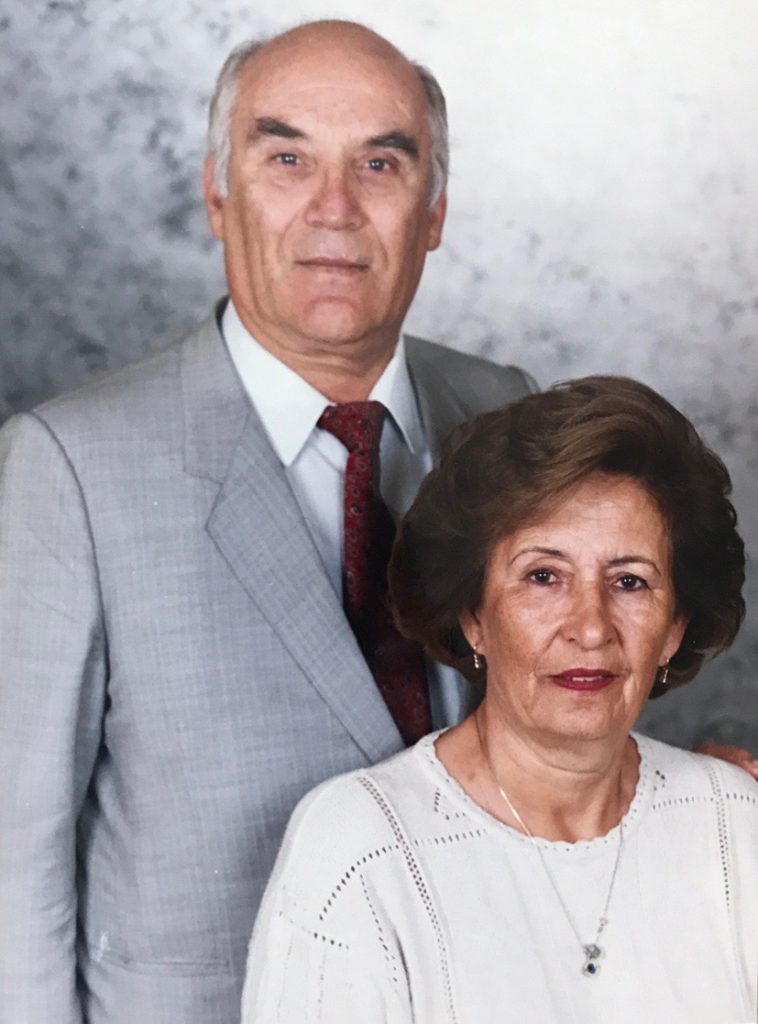

I quickly settled in the UK and got married in 1957, in Deptford. Osman, my best friend, was also my best man when I got married.

My wife was from Istanbul and worked as a registrar at a hospital. She was holding a job which at that time in Britain only a few Turkish people had. She was always a big support and help to me for whatever I did.

We had two children and two grandchildren and we both had a wonderful life together. Unfortunately she died in 1999. I married my second wife in 2000.

What did you do for work in Britain?

I had a good reference from the British Embassy in Ankara, which I used to apply to British Telecom in 1953. I ended up working there for 32 years, until my retirement in 1985. I was the first Turkish person to be employed by British Telecom.

That is a huge achievement for someone who did not study electronic engineering.

Yes, but British Telecom sent me for special training in engineering and provided me with the opportunity to study in that area while working. Some years later I got Mustafa Gençsoy to work at BT too. He was a qualified electrical engineer from Turkey. He was the second Turkish person to work for BT.

Sometime later I got into business and owned residential properties. One of my properties was a big house in London, which I rented out to government officials from Turkey and later from the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) when they were visiting or residing for short visits to Britain.

It looks like you have continued to be in touch with the Turkish Government officials on a different level in London?

This time it was also partly business, renting my house to them, but also partly meeting a lot of politicians from Turkey and Northern Cyprus, getting to know them and becoming friends with them. I was even acquainted with Turgut Özal. I gave him a ride around London in my car, which was a Volkswagen, and drove him to his school.

I met very important and well known Turkish politicians and government officials during the time I was renting my house in London. For some years Osman lived in that house too.

Have you continued to be politically active in London too?

All my life I have been politically active. But in London I helped set up the Cyprus Turkish Association (Kıbrıs Türk Cemiyeti) with the aim of bringing together all the Turkish Cypriots living in Britain.

I am glad that you wrote about the association in your book ‘Avrupa’nın ilk Türk Derneği-Kıbrıs Türk Cemiyeti’ and noted that it is the first Turkish Association in Europe; now it is part of history and everyone can learn about it. Nobody realised that initially; our hard work paid off, we made history!

What do you mean when you say, “we made history”?

As you know, it was not easy setting up that association. I am one of the people who put up money to help buy the [D’arblay Street] building in Soho. At the time I put £60 from my own pocket, as did many others, which was quite good money in those days.

I remember one restaurant owner who put £5,000 and another one £2,000. The rest was borrowed from the bank and also who received a significant amount of money from the Adnan Menderes government in Turkey. I think it was £15,000.

To ensure the building never got sold – the only reason – is why we gave ownership of the building to Evkaf [Islamic Trust of Cyprus]. In this way, they became the legal guardians of the building in Soho. The real owners of that building are Turkish Cypriots living in the UK.

Many people who came to London in the 1950s and early 1960s got involved in the work of Cyprus Turkish Association. Did you play a role in the management committee too?

The Kıbrıs Türk Cemiyeti was the only place where we were able to come together as a community organisation. The majority of Turkish Cypriots attended events even if they were not active in the association.

At the beginning I was active in the management committee too. But I was also very active in Cyprus politics. We had not stopped together with Osman, continuing our active work on the issues of supporting Turkish Cypriots in Cyprus.

Osman was always in communication with Dr. Fazıl Küçük. They were frequently on the phone and talking all the time on how to make the voice of Turkish Cypriots be heard here in the UK and across the world.

Can you tell an important memory from that time?

I remember once a joint decision Osman took with Dr. Fazıl Küçük. Osman had written a letter to all the MPs and the UK Prime Minister about the worsening situation in Cyprus. I mean everyone; men, women, old and young. We both worked throughout the night printing the letters, putting them into envelopes, writing the names and sticking stamps on them.

In those days everything was done by hand, so it took a lot of time. As there was no financial support at all, I had bought all the stamps out of my own pocket. Not only me, but also many other people were financing these types of expenses as much they could afford with their own money to help the cause.

You must have also worked with Rauf Denktaş?

I knew Rauf from the time when he came to London. Throughout the years we worked together and were in constant communication. During one of Denktaş’s London visits, we managed to run a financial appeal in aid of Turkish Cypriots in Cyprus. We worked hard and with the help of a good friend of mine, who later moved to Canada, we also managed to get the appeal translated into Urdu, Bengali and some other languages, and have it published in different magazines. We raised a good amount of money and sent the funds to Lefkoşa.

Without a doubt, we should acknowledge the very hard work of everyone from your generation who arrived in Britain some seventy years ago.

The younger generation of [British] Turkish Cypriots should know that we, the first generation [to arrive en masse in the UK] worked very hard during these years in Britain. During the day, we were at our daily jobs to earn our bread and butter, and in the evening we were endlessly working for our political cause. The TRNC was not established over just one night! My generation in the UK worked hard, very hard.

Without the hard work of all the Turkish Cypriots abroad, our voices would not have been heard. Just the Turks in Cyprus trying to raise awareness about the causes of the Cyprus Problem would not have been enough. That’s a fact and it should never be forgotten.

Especially anyone working for the TRNC Government today should remember that without us, the TRNC would not have existed. That shows how important we were and still are for the Republic in Northern Cyprus.

All the financial investment which we made over the years to Northern Cyprus, whether buying a house, sending money to relatives or going on holidays to Cyprus should not be forgotten. All the investments made by the Turkish Cypriots living abroad positively affected the economic growth of the TRNC.

And I am saying this as a 90-year-old, now nearly a century old who has pretty much seen everything.

History should never be forgotten.

Thank you for your time and sharing your significant past memories with us.

Author’s note: my gratitude to Galip Bey’s nephew Eddie Ertan for taking the time to organise this interview.

Main photo, top: Galip Ahmet, 01 August 2019 © Semra Eren-Nijhar

About Semra Eren-Nijar

Semra Eren-Nijhar is an author, sociologist, documentary film maker and policy consultant on diversity, migration, Turkish people living in Europe and the Executive Director of SUNCUT.

She is also the founder of the ‘Turkish Heritage in the UK’ initiative and the founder of Turkish Heritage Day in London, which was launched on 8 December 2014 in Enfield, North London.