Those familiar with the British Turkish Cypriot community may well wonder how such a question could even arise. After all, Turkish Cypriots are highly secular and the younger generations well integrated into British society. So well integrated, that most know very little about their Islamic roots.

It’s a topic actor and playwright Cosh Omar explored in his 2004 play The Battle of the Green Lanes. Erol, the lead character, is a young British-born Turkish Cypriot eager to define his identity. Both his father and uncle are super-patriots, sporting posters of Atatürk in the family-owned café. Erol’s friends include Greek Cypriots. And yet it’s the Muslim missionaries who draw him in, encouraging Erol to abandon his Western lifestyle and values and instead take up a holy jihad to help create an Islamic state.

At the time, the play seemed as far-fetched as it could from the lives of young Turkish Cypriots, who like other young Britons like to drink alcohol, go out and have fun. Yet the story was based on Omar’s own experience of extreme Islamist group Hizb ut-Tahrir.

The problems around extremism have rarely been out of the media spotlight, especially after the recent terrorist attacks in European capitals. These and the hundreds of young radicalised European Muslims heading to Syria – among them those of Turkish origin – should make us all more wary. Indeed, a news story which broke at the start of this year showed how close to home the issue really is.

In January, the British media was awash with photos of a young boy promoting ISIS. The child was identified as five-year-old Isa Dare, pictured above, the son of Londoners Grace Dare and Deniz Yoncaci.

The following month, ISIS released a propaganda video showing three men being strapped into a car and blown up. A child – thought to be Isa Dare – is seen with his hand on the detonator shouting ‘Allahu ekber’ next to the burnt wreckage.

Deniz Yoncaci’s son the poster boy for ISIS

With Isa the new poster boy for ISIS, the media sought out his father for comment. Deniz has refused to talk to reporters, although his mum Melek Halil said: “We’re both distraught.”

As the press homed in on how Dare’s mother Grace, a 24-year-old Muslim convert, had taken her son into a war zone and allowed him to be brainwashed and used as propaganda fodder by ISIS, T-VINE was curious to find out about Isa’s father and how his son came to be caught up in the world of Islamist extremists.

Of Turkish Cypriot heritage, 26-year-old Deniz reportedly tried to get his son back in 2014. He flew out to Cyprus intending to cross into Syria from Turkey. His family members begged him to stop given the dangers involved, prompting him to abort his mission.

Yet Deniz’s first experience of radicals was right here in Britain. In his late teens, he had turned to Islam as part of his quest to learn more about his cultural roots and self-identity. Embarking on a more devout life, the South Londoner was keen to meet pious Turkish Cypriot women.

He became a regular visitor to Lewisham Islamic Centre, where he met and married Grace, a Catholic of Nigerian ancestry who had converted to Islam during her college years. The centre’s mosque was also attended by the killers of Drummer Lee Rigby, Michael Adebolajo and Michael Adebowale, and others known for their more extreme interpretations of Islam. It’s thought this circle may be behind Grace’s radicalisation.

Deniz’s desire to be a good Muslim did not extend to the more militant interpretations of Islam, which his wife was eager to pursue. As a result, their 2010 marriage was short-lived. Soon after their son Isa was born in 2011, the couple split and subsequently divorced.

Having changed her name to ‘Khadijah’, Grace fled to Syria in 2012 taking Isa with her. There she remarried an ISIS fighter, Abu Bakr, a convert from Sweden, and was filmed with him and Isa in a Channel 4 documentary broadcast in 2014.

As T-VINE probed the issue, it became clear Deniz’s story is not isolated. Many other young Turkish Cypriots have also been exposed to radical Islamism here in Britain. One such person, who asked not to be named, gave us an extensive insight into the world of young British Turkish Cypriots turning to Islam, including Deniz Yoncaci:

“I met Deniz many years ago in London. I met him a few times but lost touch with him around about the time he got married in 2010. I was really saddened to read in the newspapers that he had got a divorce and that his ex-wife had taken their son to join ISIS. At the same time I didn’t find the news very shocking, as Deniz was not the first Turkish Cypriot I knew who had gone through such an experience.”

“Another young Turkish Cypriot man I knew, like Deniz, had also married a convert to Islam. Together they had a son. After their divorce a few years later, she also took their child and went to Syria to join ISIS. But the last I heard, she regretted her decision and winded up coming back to the UK. My friend and his son are now reunited.”

While he didn’t know Deniz very well, the unnamed source said he was struck by his innocence and naivety.

“He was only 19 or 20 years old when I met him, and had only recently started becoming interested in Islam. He was very eager to get married. In fact, just a few months before he married Grace, he called me on the phone and asked if I knew anyone suitable for him as a wife, because he assumed that I knew a lot of religious Turkish Cypriot girls. I told him that if I knew of such girls, I would marry myself off first, so unfortunately I couldn’t help him.”

“Not long after I heard he got married, so I guess he didn’t actually spend much time getting to know Grace before they tied the knot. Despite this, I was not very concerned at the time because Deniz was just one of many young Turkish Cypriot men I knew in London who had recently started practising Islam and were looking for a practising Muslim wife to help them out spiritually.”

“I too was trying to learn more about Islam at the time, and I was really eager to meet other Turkish Cypriots like me. To my surprise I met many of them. They were scattered all over London and were mainly loners looking for friends from the same cultural background who shared this same interest.”

Young Turkish Cypriots turning to radical Islam are ‘mainly loners: unconfident, naive and mentally weak’

Many Turkish Cypriots born and raised in London who choose to embrace their Muslim faith often face a severe backlash from family and friends. While some receive support, and as a result develop a more moderate understanding of Islam, many others have experienced rejection and are isolated from those they had traditionally leant on and trusted for help and advice. Our unnamed source explains:

“Those in the latter category have been put through a hard time by their families for even demonstrating the slightest inclination towards religious and conservative values.”

“One girl I knew was beaten by her father because she came home one day wearing a headscarf. After that she was afraid to start practising Islam even though she really wanted to. Another guy I knew was homeless because his family threw him out when he started becoming religious. He also rushed into marriage twice, and winded up divorced within the first three months on both occasions.”

Attitudes in North Cyprus also exacerbate matters: as TRNC society increasingly adopts non-religious lifestyles, those from Britain find it hard to know where to look for role models. Expecting to find inspiration and support in their ethnic homeland, British-born Turkish Cypriot Muslims often experience the complete opposite, being ridiculed simply for choosing a more devout life. The experience is compounded by those whose Turkish language skills are limited and so are unable to defend themselves from the many negative comments and intolerance they face.

“They [British-born Turkish Cypriot Muslims] had all visited Cyprus in the past, but mostly felt no affiliation to Cyprus and could not speak Turkish. In fact, many of them despised going to Cyprus because of the pressure they faced from their families to drink alcohol.”

“They didn’t want anything to do with the Turkish Cypriot community, but they also felt uncomfortable mixing with Muslims from other backgrounds because they found it difficult to relate to people who had not experienced the same troubles at home that they had. So naturally, they gravitated towards other Turkish Cypriots [in Britain] they found who had also gotten into the religion.”

The Lewisham group were like ‘the more the hardliner, the better the Muslim’

One group of newly-practising Turkish Cypriots were located in Lewisham, southeast London. This cluster of mainly young men, all born and raised in London, formed a close network of friends. Our unnamed source was often among them.

“Unlike most of the newly practising Turkish Cypriots I met, they seemed more confident in themselves. I remember meeting one who had a long beard and was dressed in traditional Muslim clothing. I asked how long he had been practising and he told me that he had become a Muslim just a week earlier. I was confused because clearly his beard had taken more than a week to grow, and generally speaking it takes a while for a newly-practising Muslim to develop the confidence to start wearing traditional clothing. Plus I was dumbfounded by the idea of him converting to Islam.”

“Most of the Turkish Cypriots I met described their transition as one from being a non-practising Muslim to becoming a practising one. But this young man, like many in this group, seemed to have the idea that anyone who is not practising Islam is by default a non-Muslim.”

“Among them I met another boisterous character who was full of praise for Osama bin Laden. I did not intend on debating his political beliefs, but I was shocked that he was so open about his controversial views and the fact that no one seemed willing to challenge him. It was almost like they had the impression that the more the hardliner, the better the Muslim.”

“They spoke very little about religion and spent more time refuting Muslim scholars according to their own interpretation of Islam. They were particularly fond of a Yemeni-American preacher called Anwar al-Awlaki, who was later killed in a US drone strike in Yemen for allegedly helping Al Qaeda.”

The group were quick to push their views on others, including fellow London Turkish Cypriots, and would also belittle beloved personalities, which did not go down well in the community.

“One [of the Lewisham group] had been invited to give a talk to Turkish Cypriots at a mosque in Palmers Green and had almost started a fight by beginning his speech insulting Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and the late Sheikh Nazim el-Kibrisi. I think they saw themselves more as revolutionaries rather than missionaries.”

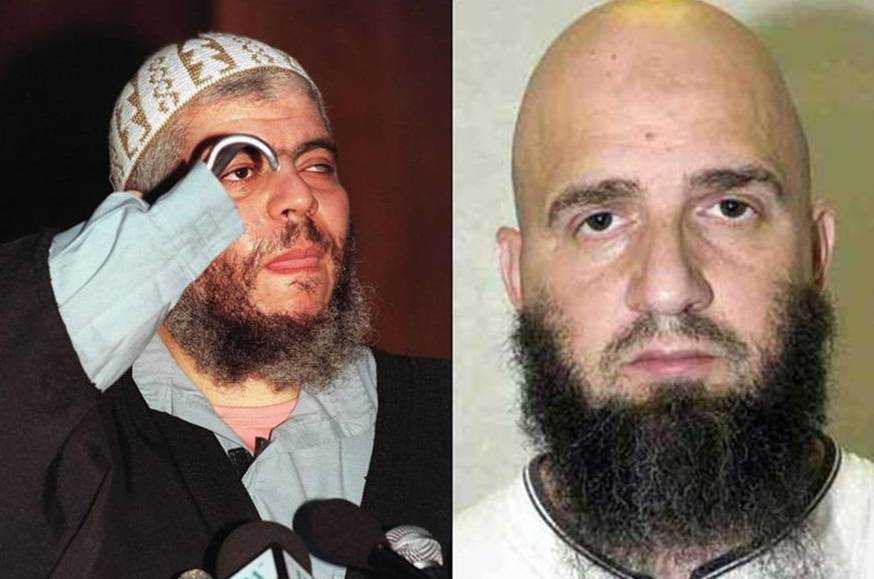

Hate preacher Atilla Ahmet told Sky News he hoped there’d be more attacks like 7/7

Turkish Cypriots looking for more radical idols needed to look no further than Lewisham’s Atilla Ahmet. Adopting the more Islamic name of Abu Abdullah, the former Sunday League football coach came to be regarded as one of “Britain’s most vile extremists” following his close association with hook-handed hate preacher Abu Hamza.

“Atilla Ahmet was sent to prison for a number of years after video evidence emerged of him attending a militant training camp in the north of England and was also recorded in an audio discussing the 7/7 London bombings. He even gave an interview to Sky News in which he said he hopes more attacks like 7/7 would happen in London.”

Known for his volatile nature, Ahmet was said to have embraced radical Islam back in 1998. He was frequently seen by the side of Abu Hamza, giving the same hate-filled sermons both inside and outside of Finsbury Park Mosque, which became tarnished following its affiliation with extremist Islamists.

After Hamza was arrested in 2004, Ahmet took over his notorious Supporters of Shariah group, thought to be a terror recruitment cell. He became one of the most outspoken Muslims in Britain, urging fellow Muslims to commit atrocities in the name of “self-defence”. His inflammatory views were regularly aired by the media.

In one 2006 interview for CNN, when reporter Dan Rivers asked what his reaction was to the September 2001 attacks on the Twin Towers in New York, Ahmet replied, “Every sincere Muslim was pleased”.

In 2008, Ahmet confessed to soliciting three counts of murder. The then 43-year-old married father of four was sentenced to seven years in jail.

His influence on the Lewisham group of Turkish Cypriots was no doubt significant, as were the others he attracted that played on the vulnerabilities of the younger men they recruited to their radical cause. It was a striking aspect not lost on our unnamed source.

They target young Muslim converts or newly-practising Muslims who don’t know much about Islam

“Another thing that struck me about this group was the whole senior-junior structure. The younger ones, mostly guys who had only recently started practising Islam, all seemed a bit lost. This includes Deniz. I saw guys like him as unconfident, naive and mentally weak, but they were all kind-hearted young men with a genuine enthusiasm to become better Muslims.”

“Most of them were simply concerned about getting married as soon as possible because deep down they all understood how isolated they were in society and that was a major source of emotional insecurity for them. Marriage offered them the spiritual and social security they craved.”

“Of course they would have all preferred to marry religious Turkish Cypriot girls, but they didn’t know any, so in the end they all opted to marry girls from a predominantly Afro-Caribbean background who had converted to Islam.”

“Like Deniz, they met their wives through the Lewisham Islamic Centre, which has been known for controversy in recent years, particularly after it was revealed that the killers of Lee Rigby also attended that mosque. I visited the mosque once many years ago and found that it was particularly popular among converts and newly-practising young Muslims. The congregation also hosted many Turkish Cypriots and even a Greek Cypriot convert who I met there.”

“A lot of them would spend their entire day at the mosque either worshipping or just hanging out together because they didn’t like going home and being around their parents. Sticking together gave them a sense of strength and the group pretty much became their new family.”

None of them seemed to be working, yet none had money problems

“As for some of the older ones in the group, I found them all a bit suspicious. The first thing I noticed was that none of them seemed to be working or capable of holding down a proper job, yet none of them had money problems. It was clear to me that they were getting an income from somewhere, but they would avoid answering questions about their personal affairs.”

Lewisham is not alone in having suspect, yet highly influential Muslim preachers who do not work but seemingly have no financial worries. Like missionaries, they pop up across London showing a great deal of interest in young Muslim men in particular, impressing them with their hospitality and eloquent speeches about Islam and politics. Yet few have studied Islam in any depth and are often unknown to the Islamic teachers in the capital.

“The source of their knowledge and learning is unclear, but they hold great influence over the thinking of Muslim youth, and they particularly target young Muslim converts or newly practising Muslims who don’t know much about Islam.”

“Once, when I was still new, one of the older Turkish Cypriot guys who did not live in Lewisham but had close ties to the group invited me and a friend to his house. He showed us jihadist propaganda videos from the war in Iraq and then read some verses from the Quran to us on the topic of war. Afterwards he told us that the Quran teaches us to ‘behead the disbelievers wherever we find them’.”

Naïve Turkish Cypriots told the Quran teaches to ‘behead disbelievers’

“I began questioning whether or not my faith really teaches this. Luckily, my friend, another Turkish Cypriot who unlike me was raised to be a practising Muslim by his father and had been learning about Islam since he was a small child, pointed out that this guy had taken the verses out of context. If it wasn’t for that friend of mine, I too might have come under his spell.”

“Unfortunately, another Turkish Cypriot friend briefly did fall under his spell, and was later investigated by police for researching how to make bombs on the internet. Thankfully, that friend later realised his error and changed his ways.”

“I kept in touch with some of the guys connected to the Lewisham group until 2012. By then the war in Syria had started and it was a hot topic of discussion. I got into a disagreement with one of the older guys over the war. While I criticised Muslims going from Europe to fight in Syria only to wind up killing other Muslims, he was arguing that it was perfectly fine because he saw those fighting on the side of Bashar al Assad’s regime as disbelievers. Funnily enough he too was unemployed but somehow had the money to support two wives and six children.”

“After that I decided to distance myself from the group completely and focus my attention on my more moderate Turkish Cypriot religious friends. Every now and again I hear some updates about the Lewisham group.”

“I was told recently that one young Turkish Cypriot man from there had gone to join ISIS and was killed, but I wasn’t told his name. Quite frankly I would not be surprised if it’s true, and I expect a number of them have either joined ISIS or at least thought about joining. I just hope that at least some of them have corrected their interpretation of Islam and now follow a more moderate path.”

Turkish Cypriots suffering from an identity crisis are at most risk

Ertan Karpazli, a news editor at TRT World and the Cezire Dernegi (Association) representative in Turkey, fired this warning shot for London Turkish Cypriots.

“Although I highly doubt ISIS will infiltrate the Turkish Cypriot community, we must acknowledge the fact that recruiters for militant groups like ISIS are working in places where the Turkish Cypriot Diaspora is found and are attracting hundreds of young men and women to sign up to fight abroad.”

It’s not clear how many British Turkish Cypriots have been radicalised to date. The TRNC authorities estimate that between 20 and 30 individuals, primarily young men, have tried to make their way to Syria via Cyprus in recent years, and the government remains alert to the threat of more trying.

British-born Karpazli, himself of Turkish Cypriot heritage, suggested why some younger members of the community are in danger of radicalisation:

“Unfortunately, due to the shortcomings of the Turkish Cypriot government, which has not sufficiently concerned itself with the plight of second and third generation Turkish Cypriots born in the UK and Australia, as well as the failure of families to raise their children with a firm Turkish Cypriot identity and attachment to their homeland, many young Turkish Cypriots born abroad suffer from an identity crisis.”

“Nowadays we see young Turkish Cypriots adopting various cultural identities: while some have adapted to their surroundings, others are experimenting with identities. Religion is one of the ways they find themselves, either by seeking closeness to God through Islam, or by changing their religion completely. Even within a religion, there are a range of narratives, some more extreme than others.”

“In their search to attain a sense of belonging, some Turkish Cypriot youth may be vulnerable, falling prey to predators who seek to radicalise them.”

As Karpazli told T-VINE, some young people from the community have already fallen into this trap and it may be too late to save them now. However, there’s still time to stop others from making the same mistake.