One of the best ways to learn a foreign language is to delve into a country’s history and learn about the incredible figures who played a pivotal role in shaping their nation’s future and identity.

One such person is María Remedios del Valle, who is described by many Argentines as “Madre de la Patria” – the ‘Mother of the Country’. She was born in Buenos Aires in the eighteenth century. Today the city is the capital of Argentina, but 250 years ago it was a colony of Spain.

María’s exact date of birth is unknown, but in a testimony rendered in the Diario de Sesiones of 1828 (an act of Congress), it is stated that she was “sixty or more years old”, placing her year of birth around 1766-68.

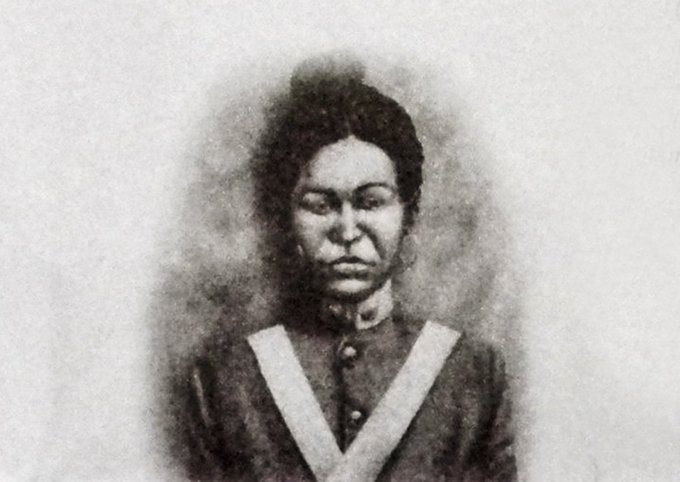

Her past lineage is also unknown, but according to her military record she was a ‘parda’ – one of the categories applied to descendants of African slaves.

María married and had two children, one of whom was adopted. Sadly, the names of neither child are known. María also participated in Argentina’s War of Independence.

María Remedios, along with her husband and two children, accompanied the Army of the North that had been deployed to liberate Peru and Upper Peru (now Bolivia) from Spain. This was the first military expedition to the interior, and the army left Buenos Aires on 20 June 1810, under the command of Bernardo Joaquín de Anzatequi.

Initially, María was among the camp followers who were recruited from the urban poor and rural peasants to follow the troops, providing cooking and nursing services, transporting weapons, ammunition, and gathering information that could help military soldiers.

Before the Battle of Tucumán, María requested permission from General Manuel Belgrano to care for the wounded and fallen soldiers at the front. General Belgrano denied this request, claiming that women were not trained for frontline service.

Ignoring his decision, María proceeded with her plan. She was later recognised by General Belgrano, who, dazzled by her dedication and loyalty, gave her the rank of captain.

During the Battle of Ayohuma, on 1 October 1813, María was wounded and taken prisoner by the Spanish forces. While she was held in captivity, she helped several prisoners escape, for which she was sentenced to be publicly flogged for nine consecutive days. That she survived such a severe beating was a miracle, and the scars on her back remained for the rest of her life.

María eventually also managed to escape and returned to the army to help the wounded on the battlefield, remaining in the army until the war ended in 1818. It was only then that she learned that her entire family had been killed. Sadly, there are no records of where and how, or in which battle her husband and sons lost their lives.

When the war ended, María returned to Buenos Aires. On 23 October 1826, she requested a pension for the services provided by her family during the Argentine War of Independence, but her claim was denied.

Unable to find a decent job due to her age and health problems, she eventually turned to begging in order to survive.

It is difficult to imagine the immense physical and psychological pain that this poor woman had to endure day after day, thinking about the family she lost, enduring the many wounds she sustained in battle, while living alone in total destitution.

She was left all alone with painful memories, wearing the few tattered and torn fabrics she possessed, barely able to protect herself from the elements as she begged for food just to survive.

Fortunately for María , she was discovered by an angel who went by the name of General Juan José Viamonte, who recognised her in the streets in terrible conditions, and came to her rescue. General Juan José immediately put in a new request on her behalf for the State to provide a pension for the poor woman.

Many other senior military officials, including Anzoátegui, supported Juan José’s request. In particular, General Eustaquio Diaz Velez testified that María had not only served bravely and honestly as a guerrilla, but had also helped and cared for soldiers wounded in battle. Colonel Hipólito Videla also confirmed that María had been wounded and imprisoned in Ayohuma.

An examination of her body confirmed that she had six scars that had been caused by bullets and swords during battles, as well as many scars on her back from the whipping she received as a prisoner.

Argentine statesman and lawyer Tomás de Anchorena, who was also a member of the Congress of Tucumán, also presented a case in her defence. These representations led to the legislature finally approving a pension for María that was paid during the last decade of her life.

Her pension was given to her as a rank of infantry captain. This was later elevated to compensation as a cavalry sergeant major.

María was placed on inactive status, with full salary corresponding to her rank in 1830. She continued to receive a pension until her death in 1847 at the age of 78-80. During this time, she also acquired the surname Remedios Rosas, though it is not clear why.

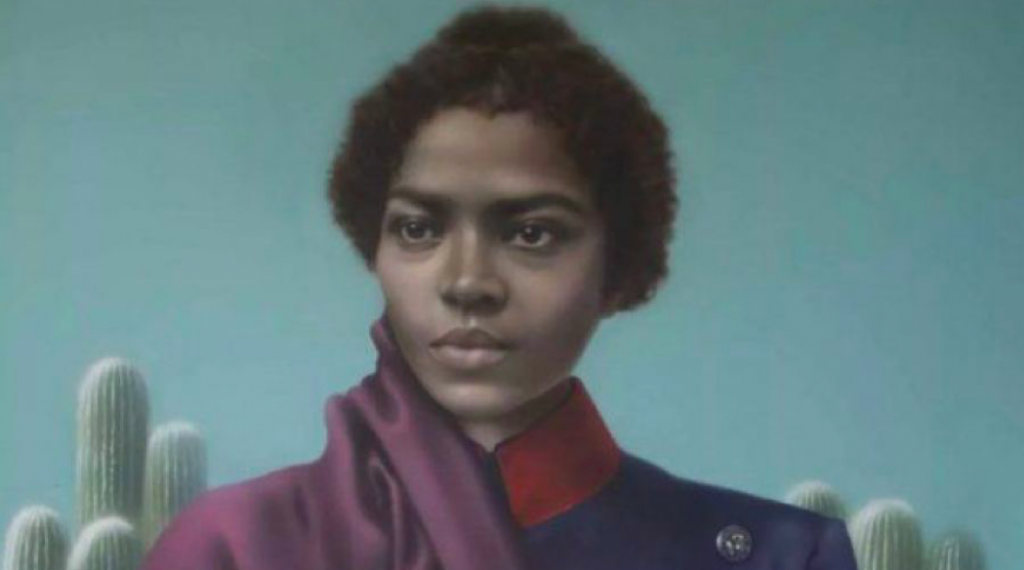

María recorded as the “Mother of the Nation”

In the pension records of the military archives, it is indicated that on 8 November 1847 Rosas -then known as the “Mother of the Nation” – had died.

This is the first significant proof that her incredible sacrifice, bravery and contribution to Argentina’s independence were recognised. Unfortunately though, over time this was initially forgotten.

While Argentine writers recorded everything about the War of Independence, the first time María appeared in a history book in Argentina was in the early 1930s, when Carlos Ibarguren published her story. A decade later, in 1944 Buenos Aires, a street was named after María in her honour.

She was again largely forgotten until the 21st century, when Argentine historians began to include the contributions of African Argentines. However, today María Remedios del Valle is now widely recognised for her contributions to the nation’s independence, and numerous publications have retold her story.

Since 2013, the 8 November is celebrated in her honour, as part of the National Day of Afro-Argentines, and Africa Culture and María is widely regarded as the “Mother of the Nation.”

In 2021, she also became the first woman whose portrait hangs in the Argentinian National Congress, and she is also on a 500 pesos bank note, together with General Belgrano.

In addition, some schools bear her name, including the María Remedios del Valle Secondary Education School, and Jardín de Infantes. These are located in the south of the city, where María was born.

For visitors to Buenos Aires, the street that bears María’s name is next to the May 25 metrobus, south of the district of General San Martín el Libertador y Padre de Argentina.

Unfortunately, on 28 February 2020, it was reported that a sculpture dedicated to María, which was on Avenida San Martín Oeste, had been damaged by vandals, prompting a major public outcry.

The manner in which María is now revered and respected is a testament to the importance of capturing and retelling history not just about leaders, but also about those extraordinary people whose bravery and sacrifices made a material difference to the lives of an entire nation.

María was a black Argentinian woman who went from mother to nurse, and then frontline military captain and national heroine. She saved many people from death, while she herself was captured and flogged for days for helping soldiers escape to freedom. That so many high-ranking generals came to her aid when she was destitute is also a testament to the goodness in human nature.

It may not have eased the psychological trauma that she faced, but at least María lived the final years of her life in dignity, knowing her many sacrifices for the revolutionary army had been recognised. And that is perhaps one of María’s most enduring legacies: for the people of Argentina to have the right to live in freedom and dignity, and why her title as “Mother of the Nation” is most fitting.