For many years now, I have dedicated my time to researching the 1,400 year Islamic history of Cyprus – a history as old as Islam itself.

This passion of mine involves a lot of reading and rummaging through historical archives to uncover the lives of long forgotten historic personalities and a heritage that can often seem alien to many in Cyprus today due to its marginalisation from the mainstream narrative about the island.

My research, however, is not solely restricted to books. I have been fortunate enough to have visited many historic sites across Cyprus and documented my findings.

Despite having presented a seminar on the ‘Pre-Ottoman Muslim History of Cyprus’ in 2020, there is still so much more for me to discover and learn about the island’s Islamic heritage and its early Muslims.

Rather predictably, limited attention is given by Byzantinists and Orientalists towards the Muslim Arabs of the era. Instead, they are usually labelled “pirates” who were a menace to the island, while refusing to acknowledge any of these Muslims’ cultural legacy and achievements in Cyprus.

Whether through ignorance or anti-Arab/Muslim bias, this exclusion of early Muslim history on the island has shaped modern perceptions. As such, it is important for us, the inheritors of the Muslim civilisation in Cyprus, to know our heritage and take ownership of the narrative!

Early Arabic inscriptions in the Kufic script

I walked past the tourist-filled sandy beaches of Baf/Paphos, making my way to the ruins of Limeniotissa. Upon finding the site, I felt honoured to be stepping foot on the location once inhabited by our pious Muslim predecessors.

Enthusiastically beginning the site inspection, I took many photographs of my findings and spontaneously began a recording, whilst providing a brief historic commentary. I surprise the viewers with special findings – early Islamic inscriptions – that I came upon at the site.

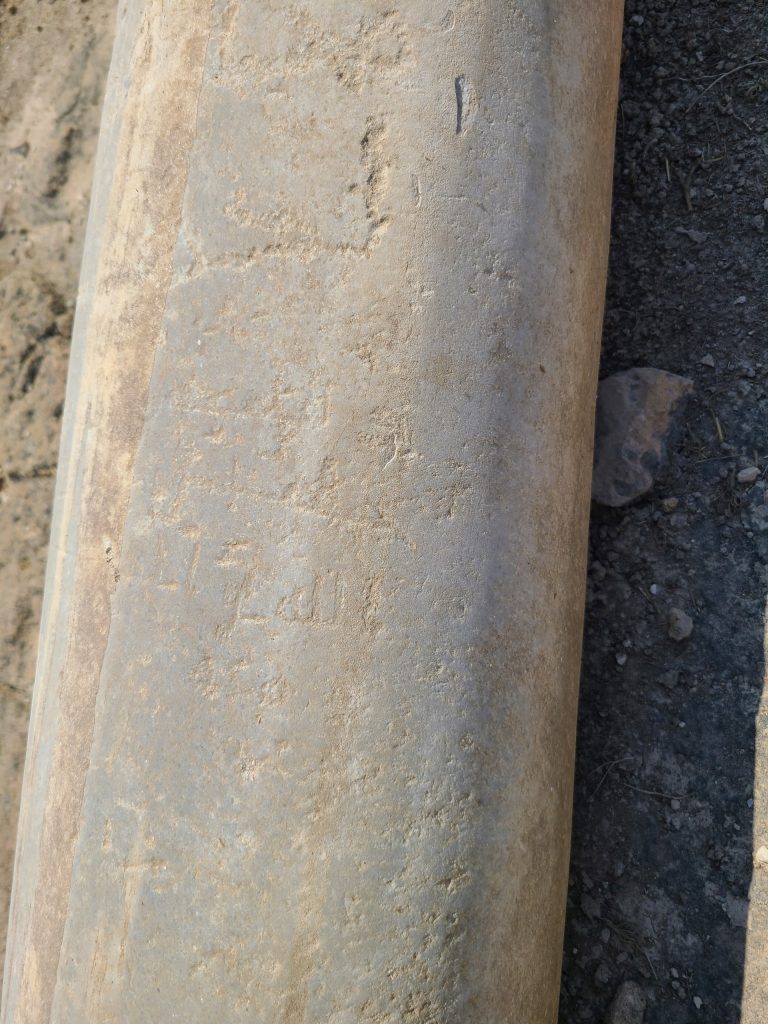

Most striking is a pillar with early Arabic inscriptions in the Kufic script, amongst which is written the name of the most High: ‘Allah’.

The site is important, not just for the heritage of Cyprus, but also for world heritage. Early Islamic inscriptions in the Kufic script, some dating back from the lifetime of the Prophet’s companions, are rare finds.

Despite the significance of the site, it is left in the open, unprotected from the elements. In stark contrast, we can view how well the Greek Cypriot authorities have preserved the remains on a nearby site dating back to the Roman period.

History of Cyprus’ early Muslims

One of the distinctive features of early Islamic history is its rapid expansion. Within a hundred years of the Prophet’s death in 632 CE, Islam had spread both east and west.

The Mediterranean Sea had become dominated by the Muslims; the Islamic Mediterranean included islands such as Crete, Sicily, and Majorca and Cyprus, which is the largest island of the Middle East, and the third largest in the Mediterranean.

The strategic location of Cyprus – a key route into Istanbul from the Holy Land (modern-day Saudi Arabia) would have meant the Caliphate would have sought out early and important ties with the island. Not surprisingly, Cyprus is also the final resting place of Hala Sultan (Um Haram) – the aunt of our beloved Prophet.

Historically, Cyprus was the location of the first naval campaign of the Caliphate, which our beloved Prophet had predicted during his lifetime. He had shared these glad tidings, stating that his companions will make the voyage “like kings on thrones”, which were recorded in authentic narrations and captured in two hadiths, Sahih al-Bukhari and Sahih Muslim.

The cherished companions honoured this green island in the eastern Mediterranean with their presence, and for some, as is the case for Um Haram, made the island their final resting place.

Though victorious against the Byzantines (also known as Eastern Romans) who dominated the island at the time, the Muslims agreed to a peace treaty. This established a power-sharing condominium between the Caliphate and the Eastern Romans, with one of its clauses stipulating the neutrality of the Cypriots.

The Christian Cypriots, however, were not faithful to the agreement, and chose to support Roman aggression against the Caliphate soon after. This resulted in another campaign, led by Abu’l-Awar (also a companion of the Prophet), along with the early Muslims so they could once again secure the island and reinstate the aforementioned peace treaty.

To ensure that there was not a repeat of such betrayal, the Muslims settled the island with a mix of soldiers and settlers from Baalbek (also known as Heliopolis), a city east of the Litani River in modern-day Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley.

Muslim Arab barracks at the ruins of Baf’s Basilica of Panagia Limeniotissa

Classical sources and modern archaeological findings indicate that the strongest presence of the Muslims was most likely at Baf.

It was here, at the location of the ruins of the Basilica of Panagia Limeniotissa, that the Muslims established a military barracks, which included workshops, stables and living quarters. They also built a tower in its narthex, which may have served as a minaret or watchtower or both.

After the Muslims of Cyprus were expelled, a smaller three-aisled vaulted basilica was erected on the same site, which was destroyed by a severe earthquake in 1159 CE.

The condominium first established by Emperor Justinian II and Caliph Abd al-Malik in 680 CE lasted some 300 years, up until the reign of Eastern Roman Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas, who decided to take complete control of the island. His actions brought to an end the first Christian-Muslim Cypriot co-existence.

The Ottomans, who were aware of this heritage, felt a sense of responsibility to right the injustice that had happened to these early Muslim Cypriots.

It was one of the reasons given to the Grand Sheikh (Turkish: Şeyh’ul-İslâm) Ebu’s-Suud Efendi, as the Ottomans sought his opinion and approval to mount a campaign in Cyprus. In the letter to Ebu’s-Suud Efendi, it was mentioned that:

“… a province was a part of the dominion of Islam, then after being taken by the miserable unbelievers, who ruined the schools and mosques, filling them with infidel ceremonies of worship.”

There is much that one can discern from this single sentence. Clearly, the Ottomans were aware of the past authority of the Muslims on the island of Cyprus. They knew that these early Muslims had established institutions of learning and mosques, which were taken over by the non-Muslims, who conducted their rituals at these sites.

The fate of the first Muslim Cypriots, who were overrun by their Christian counterparts, was also an important factor in how Cyprus was incorporated as an Ottoman domain. The first Firman (decree) issued by Sultan Selim II following the conquest of Cyprus on 21 September 1571 expressly stated that 20,000 ethnic Turks be relocated from Anatolia to Cyprus. The Sultan also ordered the establishment of an Islamic charitable trust in Cyprus (Evkaf) responsible for the administration of land bequeathed by Cypriot Muslims to be used for philanthropic purposes.

For most of their history, the Turks of Cyprus were referred to as ‘Muslim Cypriots’ (Turkish: Kıbrıs Müslümanları), thus making those first Muslims of Cyprus of 1,400 years ago their spiritual ancestors.

Retracing the inscriptions of the early Muslims of Cyprus

The video recording of the inspection of the ruins of the Basilica of Panagia Limeniotissa captures some of the artefacts and Islamic inscriptions from the barracks of this early Muslim Arab era, along with a commentary that can be found on the Cezire Derneği YouTube channel.

The video includes a segment at the end with photographs from the site depicting other early Islamic inscriptions also discovered in Baf.

Author: Mustafa Kureyşi is the chair of Cezire Association, a British Turkish Cypriot cultural organisation formed in 2008 that is dedicated to researching and raising awareness of Turkish Islamic heritage on the island of Cyprus.