Sunday 11 November marks the centenary of the Armistice which brought an end to the hostilities of the First World War in which millions perished. The anniversary will be a chance to pay tribute to the fallen, with thousands of remembrance services taking place in the UK, France and around the world.

An estimated 40 million people died between the outbreak of the war on 28 July 1914 and the armistice four years later. While each nation will naturally focus on honouring its own heroes who made the ultimate sacrifice for freedom, it will also be a time for the leaders of former enemy nations to come together to mourn the huge human loss from this terrible conflict and to pledge peace for future generations.

Turkey’s President Erdoğan and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, whose nations formed a losing alliance during the First World War (WWI), will be in Paris for the commemorations along with dozens of other world leaders, while German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier will join the British Royal Family to lay wreaths at the Cenotaph during Remembrance Sunday.

Queen Elizabeth II attends Remembrance Sunday service, 8 Nov. 2015

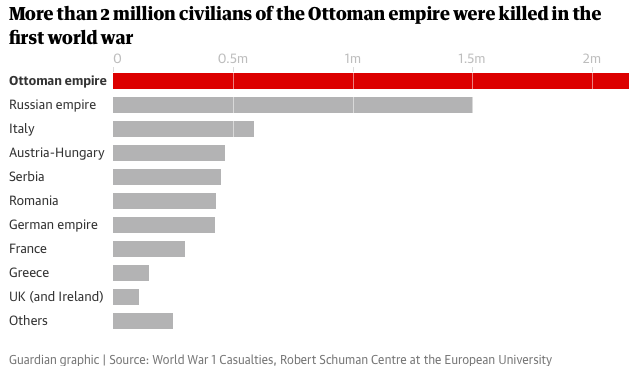

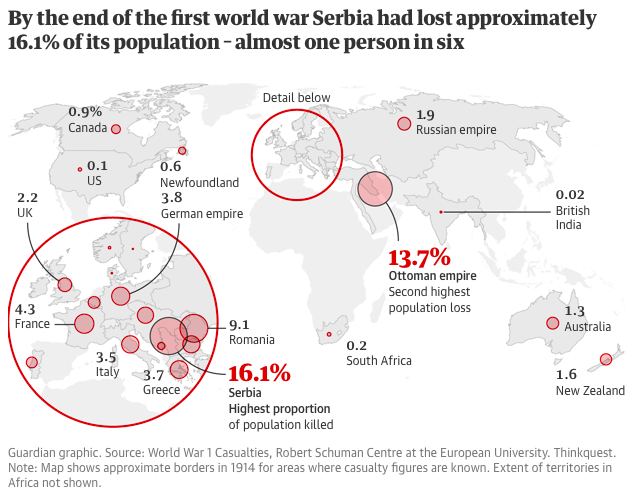

An article in today’s Guardian, Beyond the cenotaph: communities prepare for armistice centenary, brought home the extent of the human tragedy that engulfed the nations who fought in the Great War. Graphics displayed the deaths according to country, breaking this down into military and civilian casualties, and also loss of life as a percentage of the total population.

Germany experienced the greatest military losses in WWI, with more than two million deaths. Serbia suffered the single greatest loss of any nation, as one in six of its population (16%) was killed during the war.

When it came to civilian lives, it was the Ottoman Empire, however, that bore the brunt. Over 2 million died during WWI as multiple battles raged across across the wide-ranging territories of the Turks, bringing the once mighty Ottoman Empire to its knees.

The Allies, comprising the British Empire, the French Empire, Italy, and Russia, eyed greedily this fertile region and quickly sought to assert their control over the rump of the crumbling Anatolian empire during WWI, exploiting ethnic tensions and nationhood aspirations among minority groups.

“Nearly 14% of the entire population of the Ottoman Empire died during the First World War”

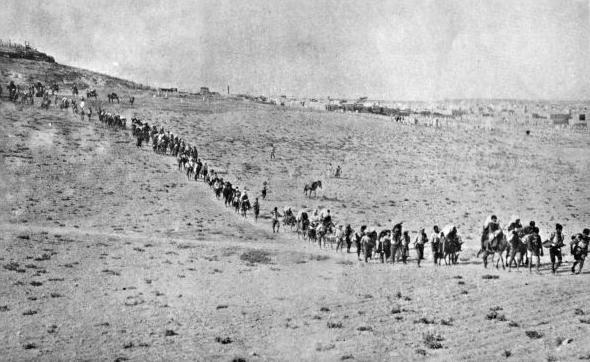

Armenians, Kurds, Turks, and Arabs of the Ottoman Empire all perished in great numbers between 1914 and 1918 due to fighting, massacres, poverty and disease. When combined with the deaths of its military personnel, which numbered some three quarters of a million men, the total number of lives the Ottomans lost during WWI equated to nearly 14% of their entire population.

In comparison, the UK lost 2.2% of its population, France 4.2%, Italy 3.5% and Greece 3.7%. The Russians paid a heavy price too, with 1.5 million civilian and 1.75 million military deaths during the Great War, yet in total this was just 1.9% of the total population of this vast country.

The French and Austria-Hungarians also endured massive military losses. The former had nearly 1.5 million troops killed in action, while the latter had over a million troops die. The story was marginally better for Britain and Ireland, who between them lost nearly a million troops too.

The catastrophic casualty numbers make the First World War one of the deadliest conflicts in human history. Yet while European states sought to reach a permanent peace deal, for the Turks the November 11 Armistice offered the briefest of pauses of an already long, brutal and bloody conflict. As one of the vanquished people, their quest for freedom and independence was far from over.

“For the Turks the Nov. 11 Armistice offered the briefest of pauses of an already long, brutal and bloody conflict. As one of the vanquished people, their quest for freedom and independence was far from over”

When a brilliant 37-year-old Turkish military commander, Mustafa Kemal, returned to the Ottoman capital Constantinople on 13 November 1918 to find it under British rule, it was a situation he could not accept. He was the only Turkish military commander undefeated during the First World War, thwarting British and Anzac forces at Gallipoli, then the Russians and Armenians in Eastern Anatolia at Bitlis and Muş, before checking Allied forces from advancing in Aleppo, Syria, and Yemen.

Mustafa Kemal and fellow Turkish military nationalists started to agitate for resistance against the foreign powers, which would formally commence when Mustafa Kemal landed in Samsun on 19 May 1919. The Turkish War of Independence would see ‘Turks’ of all ethnic backgrounds stand together in a new four-year conflict that would cost over seven hundred thousand more lives.